When it comes to ethics, people often mistakenly assume that being morally good is as easy as waking up and going to the bathroom. It just happens. While being bad takes effort, so the thought goes, being good boils down to refraining from intentionally mistreating others. Actually, there's good reason to believe that the reverse is usually true.

Being good is an achievement requiring active, conscious, intentional effort. The Buddha reminds us of as much. In chapter XII of The Dhammapada (400 BCE), written after the death of Buddha, he is credited with teaching,

“Bad deeds, and deeds hurtful to ourselves, are easy to do; what is beneficial and good, that is very difficult to do.”

The Buddha wasn’t alone in viewing moral goodness as an achievement. The Greek Philosopher, Aristotle, expressed a similar perspective in Nicomachean Ethics (325 BCE). He wrote:

“…it is no easy task to be good. For in everything it is no easy task to find the middle, e.g. to find the middle of a circle is not for every one but for him who knows; so, too, any one can get angry—that is easy—or given or spend money; but to do this to the right person, to the right extent, at the right time, with the right motive, and in the right way, that is not for every one, nor is it easy; wherefore goodness is both rare and laudable and noble” (BK II Ch:9, 25).

Aristotle was an innovator of what we, today, call “virtue ethics.” From his view, it wasn’t enough to adopt a philosophy that guided us to actions producing the greatest happiness or actions that were universalizable and endorsed by moral duty. He believed we needed to develop the right kind of character. Specifically, we needed to nurture virtuous habits of thought, feeling, and action. Doing so would ensure that we acted in the right way, at the right time, with the right people.

Having studied human thought and behavior, Aristotle, like the Buddha, saw that such ethical character and conduct was not something that just happened without significant commitment, time, effort, and knowledge. Both thinkers remind us that living good lives is an art, one that the humanities stands uniquely equipped to aid us in.

Ignorance and Guilt: Impediments to Being Good

We can identify at least two reasons why doing what is right may be more difficult than doing what is wrong. In the first place, we may simply be ignorant about what is right, believing the bad to be good. We may have so internalized the moral assumptions of our society that we fail to even recognize let alone question our own immoral beliefs and behavior.

The fact we feel confident in our beliefs, we should remember, is not evidence in their accuracy. Such confidence is often rooted in our familiarity and comfort, neither of which have an intrinsic relationship to knowledge. In “The Value of Philosophy,” British philosopher Bertrand Russell noted that the misplaced confidence many have in their beliefs is due to ignorance, not to a meaningful relationship with truth.

“The man who has no tincture of philosophy goes through life imprisoned in the prejudices derived from common sense, from the habitual beliefs of his age or his nation, and from convictions which have grown up in his mind without the co-operation or consent of his deliberate reason. To such a man the world tends to become definite, finite, obvious; common objects rouse no questions, and unfamiliar possibilities are contemptuously rejected. As soon as we begin to philosophize on, on the contrary, we find…that even the most everyday things lead to problems to which only very incomplete answers can be given.”

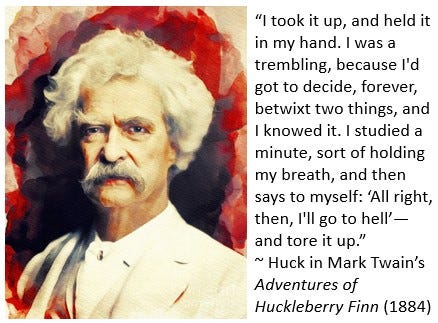

Mark Twain’s novel, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, gives us a poignant and enlightening expressions of the difficulty of being good.

One of the benefits of fruits of philosophical consciousness is that it enhances our intellectual humility by forcing us to examine what is most familiar and to fairmindedly consider what is strange and unfamiliar. The resulting intellectual humility is the wellspring of all manner of insights, including moral insight about ourselves and the wider world. At a minimum it makes us reasonably aware of our fallibility, affirming French essayist, Montaigne’s quip,

“To learn that we have said or done a foolish thing, that is nothing; we must learn that we are nothing but fools, a far broader and more important lesson.”

A second related reason doing right is difficult is that it may require risk and disapproval from others. Thinking ethically sometimes generates conclusions and courses of action that can put us at odds with family, friends, our community, and even ourselves. This can foster painful conflict. As much as we like to express our individuality, most of us desire approval from our fellow human beings—at least those we are in meaningful relation to. Our commitment to integrity is never more challenged than when our authentic moral conscience or judgment requires us to dissent from beliefs held dear by those we love and do not want to disappoint.

“Sinning” for Moral Integrity

Mark Twain’s novel, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), gives us a poignant and enlightening expressions of the difficulty of being good. In the story a young white boy, Huck, who has left home encounters and teams up an escaped slave named Jim. Jim has run away from Miss Watson, the woman Huck was placed in the care of and has run away from. Jim escaped after he heard Miss Watson intended to sell him. But when Jim gets closer to his freedom, Huck’s “conscience” assails him for befriending and helping a slave fleeing his “rightful” owner.

“Jim said it made him all over trembly and feverish to be so close to freedom. Well, I can tell you it made me all over trembly and feverish, too, to hear him, because I begun to get it through my head that he was most free—and who was to blame for it? Why, me. I couldn’t get that out of my conscience, no how nor no way….It hadn’t ever come home to me before, what this thing was that I was doing. But now it did; and it stayed with me, and scorched me more and more.”

It’s worth noting that Huck’s moral discomfort with partnering with Jim is rooted in what he perceives to be his duty and not personal benefit.

“I tried to make out to myself that I warn’t to blame, because I didn’t run Jim off from his rightful owner; but it warn’t no use, conscience up and says, every time, ‘But you knowed he was running for his freedom, and you could ‘a’ paddled ashore and told somebody.’ That was so—I couldn’t get around that no way. That was where it pinched. Conscience says to me, ‘What had poor Miss Watson done to you that you could treat her so mean? Why, she tried to learn you your book, she tried to learn you your manners, she tried to be good to you every way she knowed how. That’s what she done.”

The notion of “conscience” that Huck has in mind is what Freud called the “superego” and what philosophers would generally refer to as “common sense.” This is the internalized set of beliefs—moral beliefs in this instance—that shape our perception of the world. Huck’s “conscience” is aroused all the more as Jim gets nearer to freedom and shares his larger plan.

Jim tells Huck he plans to go to a free state to work and save up money. With that money he’ll buy his wife out of slavery from the farm near Miss Watson. Then he and his wife will work to save up money to buy their children’s freedom. If the farm owner refuses to sell the parents their children, they will get an abolitionist to “steal them.”

Huck is flabbergasted and morally disturbed by Jim’s bold confession that he would not only steal his own freedom but also that of his children.

“Here was this nigger, which I had as good as helped to run away, coming right out flatfooted and saying he would steal his children—children that belonged to a man I didn’t even know; a man that hadn’t ever done me harm.”

Driven by guilt, Huck then resolves to take action and turn in Jim. But right at the moment he has the opportunity to give up Jim to two runaway slave hunters, Huck lies to help him evade capture. The more Huck gets to know Jim the more he feels conflict between what he was taught about black people and the human being he experiences before him.

Here it’s worth considering that Huck’s guilt, like the guilt many of us sometimes feel, is not an authentic expression of our deepest intuitive moral convictions. Such guilt is often the result of a lack of intellectual and ethical independence. In “Disobedience as a Psychological and Moral Problem” (1963), Erich Fromm wrote that guilt feelings are usually due to fears surrounding disobedience to accepted cultural expectations rather than authentic moral reflection. “They are not really troubled by a moral issue, as they think they are, but by the fact of having disobeyed a command.” Many of our so-called “moral judgments” are simply conclusions derived from what Fromm called “authoritarian conscience.” This authoritarian conscience is simply “the internalized voice of an authority whom we are eager to please and afraid of displeasing.”

Eventually Huck’s building internal conflict and guilt feelings cause him to write a letter to Miss Watson, informing her of Jim’s whereabouts. Huck doesn’t write the letter because he genuinely wants to. He does it because it is his God-mandated moral duty to do so, or so he has been taught. And writing the letter does give Huck a certain sense of peace.

“I felt good and all washed clean of sin for the first time I had ever felt so in my life, and I knowed I could pray now.”

Huck’s peace and sense of being “cleansed” has nothing to do with betraying his friend and everything to do with obeying his society’s notion of moral decency. He is “right with the [social] world,” we might say. And yet he is not right within his authentic moral self. Being honest, most of us must admit that we, too, feel good when we fit neatly into those praised societal expectations. Ethics challenges us to contemplate the cost of such conformity, the cost to others—in Huck’s case, Jim—and the cost to ourselves.

Huck’s authentic moral conscience—what Fromm calls “humanistic conscience”—is not satisfied with obedience to authority and conformity to the dominant cultural conscience. He just can’t seem to harden his feelings to Jim. Jim’s humanity defies the deeply lodged stereotypes Huck had been instilled with. Reflecting on the time he saved Jim from the slave catchers, Huck looks to the letter to Miss Watson and makes a profound moral decision: he decides to destroy it and to fully embrace Jim’s freedom.

In those seven words— “All right, then, I’ll go to hell”—Twain helps us understand the difficulties of genuine moral conscience.

The decision to destroy the letter isn’t a pleasant, self-aggrandizing moment of moral glory or joy. Quite the opposite, Huck sees his decision as a betrayal of Miss Watson and his community and disobedience to God and morality.

“I took it up, and held it in my hand. I was a trembling, because I'd got to decide, forever, betwixt two things, and I knowed it. I studied a minute, sort of holding my breath, and then says to myself: ‘All right, then, I'll go to hell’— and tore it up” (Chapter 31).

In those seven words— “All right, then, I’ll go to hell”—Twain helps us understand the difficulties of genuine moral conscience. Being good—doing good—often requires us to think and behave in ways that seem to betray things we hold dear. It demands that we abandon authoritarian conscience for a humanistic conscience. According to Fromm, humanistic conscience is rooted in the human capacity to reason and our “intuitive knowledge of what is human and inhuman, what is conducive of life and what is destructive of life.”

Moral Integrity and Disobedience

Twain’s work also reminds us that none of us can live lives of genuine moral integrity without accepting the weighty responsibility of being, at times, disobedient. As Fromm wrote,

“Whenever the principles which are obeyed and those which are disobeyed are irreconcilable, an act of obedience to one principle is necessarily an act of disobedience to its counterpart, and vice versa….If a man can only obey and not disobey, he is a slave; if he can only disobey and not obey, he is a rebel (not a revolutionary); he acts out of anger, disappointment, resentment, yet not in the name of a conviction or a principle.”

Disobedience alone makes for an incomplete recipe for humanistic moral character. Yet we must also acknowledge that no one can be good who lacks the courage and independence to critically evaluate themselves and, at times, disobey the misguided, irrational moral beliefs instilled in them.

The difficulty of determining which beliefs to be disloyal to, and mustering the conviction to defy such beliefs, even at our own expense, returns us to Aristotle and the Buddha’s insight: that being good is not as easy as we are led to believe. The fact that as accomplished a thinker as Aristotle rationalized the rightness of slavery and male supremacy should give us more than enough reason to second guess the moral beliefs we take for granted.

If you found this post interesting, please share it with others and like it by clicking the heart icon. And be sure to subscribe if you haven’t already.

Invite Dr. Nall to Speak

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook or by leaving a comment.

I loved the story of Huck Finn and its symbolism. What an excelIent and important essay, which goes beyond the typical review of a novel. I needed to read this today; it has not been an easy time. Doing good has a high cost.

Doing good when the (moral) authority says good is bad is always a problem. A very difficult place to be, a lonely place to be. The lonelliness and estrangement from family, friends, most everyone that you know can make it seem that your conscience has misled you.

Yet, you keep on trodding on that lonely path, because this is the path of goodness and truth. Deviating from it would be a denial of self, of your values and your beliefs.

I know from personal experience how difficult being good can be, when I hold old-fashioned liberal views on a host of issues. Liberal views that are humane and speak of dignity of persons and of animals.

It is difficult to be good when everyone around me views liberalism with animus, disdain and makes a mockery of it. There are times I think I have entered a bizarro world; there are times I think that I am losing my mind.

Then this essay says otherwise. Thank you.🐦🦜🕊

This was recommended reading from someone else. I can see why they recommended it. A thoughtful and excellent post. Thank you