bell hooks’ Labors of Love: Taking Action, Thinking Critically

Pioneering black feminist, bell hooks challenged us to recognize thinking critically as an activity, one every bit as important as our physical undertakings.

bell hooks’ work has played an important role in my college teaching career and classroom experience. Just before I started teaching a general education course called “Creative and Critical Thinking,” I discovered a short, bold essay in her book, Teaching Critical Thinking: Practical Wisdom (2010). hooks' simply titled essay, “Critical Thinking,” was grounding and appropriately provocative.

Drawing on past thinkers like social theorist and psychoanalyst Erich Fromm, she reminded readers that thinking is an action.

“Thinking is an action. For all aspiring intellectuals, thoughts are the laboratory where one goes to pose questions and find answers, and the place where visions of theory and praxis come together. The heartbeat of critical thinking is the longing to know—to understand how life works.”

To appreciate the importance of this idea just consider how often someone thinking and talking through a problem is met with the question, “Yeah, but what are you going to actually do about it?” The implication is clear enough: neither the critical analysis nor the discussion of that analysis constitutes real action.

hooks challenged this view, reminding us that critical thought constitutes an act every bit as important as taking physical action. This is clear enough from the fact well-intended but unreflective efforts so often produce unproductive or even counterproductive results. Physical exertion without contemplation is often the result of external forces that undermine our agency and values. For hooks, critical thinking “aims to understand core, underlying truths, not simply that superficial truth that may be most obviously visible.” Critical thinking in this sense is a vital capacity not only for truth but also authenticity and autonomy.

Over the years I've replaced the obligatory first-day-of-class sermon on the syllabus with a reading of her essay. Pacing pensively around the room, book in hand, I read hooks contention that all human children—“Across the boundaries of race, class, gender, and circumstance”—are predisposed to asking questions and seeking truth. The problem, she argued, is that our social structures—from our homes to schools—deter rather than nurture this critical thinking spirit.

“Whether in homes with parents who teach via a model of discipline and punish that it is better to chose obedience over self-awareness and self-determination, or in schools where independent thinking is not acceptable behavior, most children in our nation learn to suppress the memory of thinking as a passionate, pleasurable activity.”

hooks daring criticism resounds Albert Einstein’s critique some 70-years earlier. In a 1936 speech Einstein observed that children’s natural and healthy “curiosity” for “truth and understanding” was often “weakened” early in life. The aim of school education, Einstein insisted, ought to be independent thought in the service of fundamental human values.

Over the years this critique has consistently resonated with many students. hooks’ penetrating, candid analysis and her accessible, succinct style has made her a favorite of students accustomed to dense scholarly texts lacking warmth, courage, and affirmation of the human values driving our pursuit of knowledge. “By the time most students enter college classrooms,” she wrote,

“they have come to dread thinking. Those students who do not dread thinking often come to classes assuming that thinking will not be necessary, that all they will need to do is consume information and regurgitate it at the appropriate moments…..Fortunately there are some classrooms in which individual professors aim to educate as the practice of freedom. In these settings, thinking and most especially critical thinking, is what matters.”

I ask students not to merely accept such claims but to ponder them, checking them against their experience and understanding. Have they come to this first day of class expecting to passively absorb information? Have they come to dread independent thinking for fear of the consequences they might be subjected to for saying the “wrong” thing or asking the “wrong” question?

After reading the essay I task them with putting their thoughts to paper in dialogue with her analysis. A lively conversation inevitably ensues, and I conclude class by stating that we have just exemplified the subject we will be both studying in the abstract and practicing in the classroom: critical thinking.

Critical thinking is often presented as being important because it is expected of students, will improve their grades, and will make them more employable. But bell hooks argued that critical thinking is primarily a vehicle for self-knowledge, agency—self-determination, and with it, survival and human flourishing.

Unpopular Views

bell hooks’ understanding of the life-affirming and sustaining character of critical thinking was rooted in her own life experience. hooks’ birth name was “Gloria Watkins.” She initially changed her name before publishing a book of poetry to avoid being confused with a woman of the same name in her community. “bell hooks” was her maternal great-grandmother’s name. Though initially a practical choice, the name soon became a vehicle for developing her authentic voice. Her childhood socialization left her hesitant to freely express herself for fear of saying the “wrong” thing. She wrote,

“Much of what we say is tempered and contained by fear of saying that which might be considered ‘wrong,’ and what constitutes it being wrong is the likelihood of punishment. In childhood, I was often punished for saying the wrong thing, for thinking in ways that the grown-ups around me did not consider appropriate. This early socialization had a tremendous impact on my capacity for self-expression.”

hooks confronted this fear of authentic self-expression when writing Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism (1981). She was just 19-years-old and the book expressed ideas many others thought were “wrong” and “impolite.” She found strength in her pseudonym, a strong-sounding name that allowed her to recall and channel her true voice. “Through the use of the name bell hooks,” she explained, “I was able to claim an identity that affirmed for me my right to speech.”

True to the public intellectual ideal, bell hooks refused to placate ignorance and ethical contradiction. She not only raised difficult questions and challenged views she thought faulty in the public sphere as an author and educator; she also did this in her private life, where we often have the most to lose. She took issue with educated, progressive, feminist-minded people in her social circle who rightly objected to physically punishing women, which had not too long ago been normalized by patriarchy, but found it perfectly acceptable to slap, spank, or pinch children as a means of physical discipline.

She further dared to point out that women, so often obligated to do the vitally important child care work of society, were some of the main perpetuators of violence against children, specifically their own children.

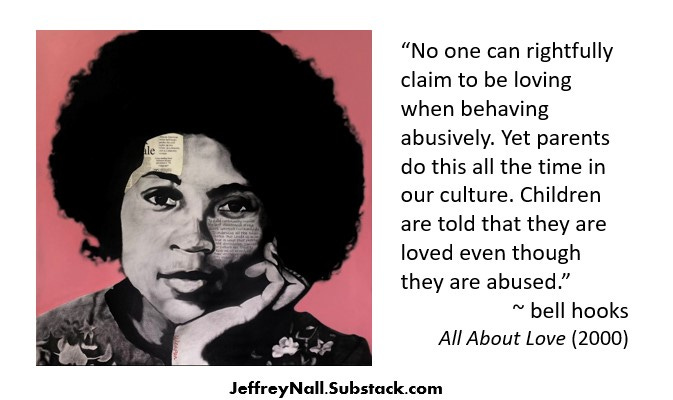

Fostering a truly healthy society required us, she argued, to disavow the notion that love can coexist with abuse and neglect. In All About Love (2000) wrote:

“No one can rightfully claim to be loving when behaving abusively. Yet parents do this all the time in our culture. Children are told that they are loved even though they are abused.”

Never one to refrain from holding men accountable for their patriarchal male privilege, hooks also dared to point out that patriarchal sexism was not kept alive only by men. As she wrote, “females could be sexist as well.” Women can and have internalized the very sexist stereotypes that dehumanize women.

hooks understood that our beliefs and understanding of the world determined our political and social commitments, and that it made no sense to determine the allies of justice and love solely on the basis of their sex or ethnicity. These categories of existence would, undoubtedly, shape our understanding of the social world, potentially gifting invaluable insights. But hooks rejected the notion that such social identities, alone, determined our essence. Her confidence in human empathy, imagination, and reason instilled a persistent faith in all members of the human family.

Read More about bell hooks

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

If you enjoyed this post please share it with others and like it by clicking the heart icon. Be sure to subscribe if you haven’t already.

Invite Dr. Nall to Speak

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook or by leaving a comment.

I enjoyed this essay; it brought to mind how important thinking is and its connection to an active love, which is not at all sentimental or romantic in the modern sense. Violence and aggression can never coexist with love. These are its antithesis.

Equallly important is discussing ideas, which often means using the Socratic or Hegelian dialectic methods. This was popular when I was in college and university in the late 1970s and early '80s. It seems to have fallen out of favour (not in your class), and in its stead there are no longer arguments but all-out verbal warfare.

Cui bono? I am not sure.

What I do see is that violence has replaced reason and love. This is why universities ostensibly have decided to institute speech codes. It is not the best solution for an open society (Popper), particularly in institutions of higher learning, but the level of sickness and violence in our society makes this a safe choice.

I do not know what the future holds, but your article is on the right track in mentioning hooks, MLK, Fromn and Einstein.