bell hooks’ Labors of Love: Visionary Feminism

Part one of a four-part series exploring the ideas of feminist theorist, cultural critic, and public intellectual, bell hooks

On December 15, 2021, the world lost one of the great public intellectuals of our day: bell hooks. Many who commented on her passing understandably focused on her invaluable contribution to understanding the complexities of gender and race. These aspects of her work do, indeed, merit focused attention. Yet so does some of her less discussed examinations of class exploitation, the price men pay for their male privilege in a patriarchal society, and what it means to think critically and uphold the fundamental principles of a democratic society including freedom of expression.

I was first introduced to bell hooks’ writings in my graduate studies in Women’s studies, at Florida Atlantic University. I was a recalcitrant scholar more interested in engaging the wider general public in dialogue than adopting academic in-group speak. bell hooks’ work spoke to me: it was direct, concise, profound, and just as important, revealed an author who was interested in the world. In a word, bell hooks cared about what she wrote about, and she made no attempt to disguise, that humanistic concern.

Dominant culture has painted a false notion of objectivity defined as detached, valueless study of a subject. As Erich Fromm, put it in Man for Himself: An Inquiry into the Psychology of Ethics (1947), objectivity is not

“synonymous with detachment, with the absence of interest and care. How can one penetrate the veiling surface of things to their causes and relationships if one does not have an interest that is vital and sufficiently impelling for so laborious a task?....

Objectivity does not mean detachment, it means respect; that is, the ability not to distort and to falsify things, persons, and oneself…. There hardly has been any significant discovery or insight which has not been prompted by an interest of the thinker. In fact, without interests, thinking becomes sterile and pointless. What matters is not whether or not there is an interest, but what kind of interest there is and what its relation to the truth will be.”

I reference Erich Fromm not only because his thinking remains as fresh, prescient, and accessible as it is insightful, but also because he is one of the authors hooks drew on again and again for insight. This much is clear from her work’s exemplification of Fromm’s conception of objectivity, as honest and respectful dealings with the truth and our interests in it over dishonest pretensions of disinterest. And I have hooks to thank for introducing me to this underappreciated but perspicacious social theorist.

Against academic trends, hooks used plain language, discussed personal experience, took popular culture seriously, and showed a genuine interest in her work and its social impact. Many of her readers don’t agree with everything hooks argues for. But few readers fail to realize the good faith of her intentions.

bell hooks’ work was motivated by compassion and justice, not tenure, accolades, or money. This is clear from the fact almost no one is unscathed by her intersectional analyses. She refused to postulate easy “enemies,” but instead took bold positions implicating most of her readers. Influential Black feminist legal scholar, Kimberlé Crenshaw, noted hooks’ rare written candor in an interview with the New York Times. “She was utterly courageous in terms of putting on paper thoughts that many of us might have had in private.”

hooks defined feminism as “a movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation, and oppression.”

hooks’ courage was buoyed by an ethic of love. Her aim was social transformation rather than personal gain and flattering readers or those in power. The very reason she chose not to capitalize her name was to prioritize the substance of her ideas over her individual identity.

Visionary Transformation, Not Reform

The accessibility and relatability of hooks’ writing reflects her lifelong concern for the lives of everyday people, the whole of the human family. hooks is widely known as a feminist, anti-racist thinker. But she wasn’t just any-kind of feminist.

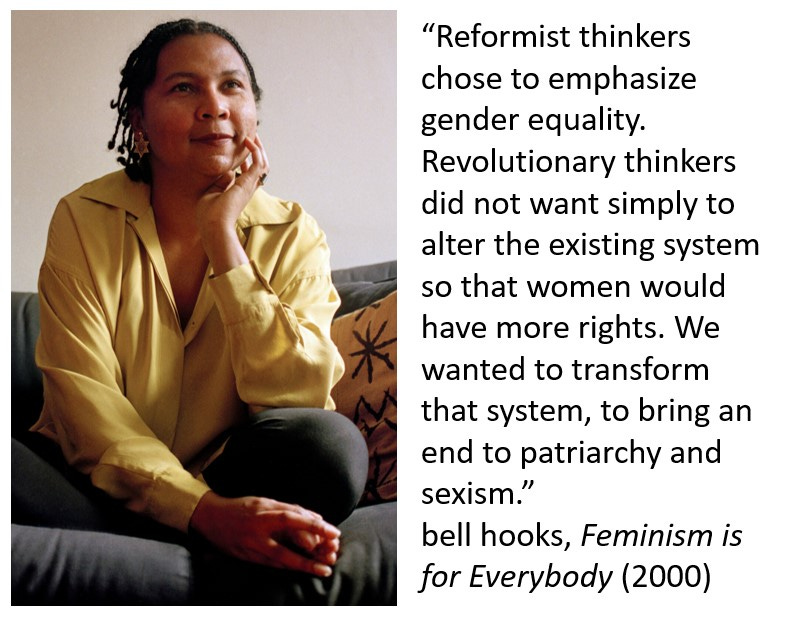

hooks defined feminism as “a movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation, and oppression.” Just as not all Christians hold precisely the same beliefs, so, too, with feminists. Divisions have always existed among feminists in terms of strategy and the larger vision of a just world they wished to achieve. Some feminists sought to reform the dominant society to create space and opportunity for women to join men in positions of power and authority.

Following the path of radical feminists, hooks viewed the foundation of patriarchal culture as itself part of the problem. She believed male supremacy was rooted in an amorphous and ever-changing ideology of human inequality and notions of superiority: superiority of men, superiority of Europeans, superiority of military might, superiority of those with wealth, superiority of heterosexuality, and so on. “Reformist thinkers chose to emphasize gender equality,” wrote hooks, in Feminism is for Everybody (2000),

“Revolutionary thinkers did not want simply to alter the existing system so that women would have more rights. We wanted to transform that system, to bring an end to patriarchy and sexism.”

As a member of the revolutionary or “visionary” wing of feminist thought, hooks believed we needed to speak candidly about the interconnectedness of

white supremacy

patriarchy

imperialism

and capitalistic economic exploitation

In this respect, hooks shared Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King’s diagnosis of America’s spiritual sickness as a triplet of evils: racism, economic exploitation, and imperial militarism. Yet hooks and her radical feminist sisters filled in a crucial gap in King’s analysis, developing our understanding of the role patriarchal masculinity feeds the triplet of evils.

bell hooks’ feminism was egalitarian and sought to address pain and suffering wherever she observed it. She refused reductive analysis of oppression and boldly challenged us all to see how ideologies and practices of dominance worked together to produce an interlocking injustice. In the video, Cultural Criticism and Transformation (1997), she said,

“I began to use the phrase in my work 'imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy' because I wanted to have some language that would actually remind us continually of the interlocking systems of domination that define our reality and not to just have one thing be like, you know, gender is the important issue, race is the important issue, but for me the use of that particular jargonistic phrase was a way, a sort of short cut way of saying all of these things actually are functioning simultaneously at all times in our lives….”

To foster a truly caring-just society we would need to go to the roots of deep-seated problems. This would require radical thought and action, not mere reform.

Listening to Black Women

hooks’ was a vital force in expanding the depth and scope of feminist consciousness. When she was just 19, hooks wrote Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism (1981), an homage to Sojourner Truth, and a critical assessment of white feminists’ racist beliefs and alliances and the lingering effects of racial stereotypes of black women.

In Feminist Theory from Margin to Center (1984) she explored the ways in which black women’s experiences and insights were pushed to the margins of the very feminist movement ostensibly purposed to advance all women’s rights.

“Much feminist theory emerges from privileged women who live at the center, whose perspectives on reality rarely include knowledge and awareness of the lives of women and men who live in the margin. As a consequence, feminist theory lacks wholeness, lacks the broad analysis that could encompass a variety of human experiences. Although feminist theorists are aware of the need to develop ideas and analysis that encompass a larger number of experiences, that serve to unify rather than to polarize, such theory is complex and slow in formation. At its most visionary, it will emerge from individuals who have knowledge of both margin and center.”

Reflecting on her experience raising the problem of racism among feminists, hooks recollected, in Feminism is for Everybody (2000):

“In those days white women who were unwilling to face the reality of racism and racial difference accused us of being traitors by introducing race. Wrongly they saw us as deflecting focus away from gender… Our intent was not to diminish the vision of sisterhood. We sought to put in place a concrete politics of solidarity that would make genuine sisterhood possible. We knew that there could [be] no real sisterhood between white women and women of color if white women were not able to divest of white supremacy, if [the] feminist movement were not fundamentally anti-racist.”

After hooks’ passing, Kimberlé Crenshaw, told the New York Times that bell hooks was “pivotal to an entire generation of Black feminists who saw that for the first time they had license to call themselves Black feminists.”

hooks and other black feminist thinkers, including Patricia Hill Collins, insisted on hearing a diversity of women’s voices, including voices of women of color, lesbian women, and poor women. In doing so, hooks helped infuse a narrowly conceived feminism with greater explanatory power, social-political relevance, and humanity. She also helped initiate the shift of consciousness many white people are now participating in, as we learn to recognize and challenge the overt and insidious manifestations of racist ideologies. The vibrance and inclusivity of contemporary feminism owes much to this pioneering thinker.

Failing to See Class

We can credit hooks, in part, with helping to change the cultural landscape such that there is a growing awareness of the necessity of listening to women of color. What is perhaps less well known is that hooks followed Rev. King in concentrating on class oppression as a central subject of concern in the last years of her life. hooks, like King, was comparably less successful in convincing the broader society of the centrality of economic class in understanding systems of human oppression. Without understanding the unique plight, concerns, and experiences of poor people our knowledge would be impoverished and our political projects striving for social justice would be half-measured.

Feminism of the 1970s was not only troubled by its ethnic-blindspots but also its class bias. While white women with comparative privilege spoke of the desire to work outside of the home, many women of color and poor white women were working. In Feminism is for Everybody, hooks wrote:

“It was not gender discrimination or sexist oppression that kept privileged women of all races from working outside the home, it was the fact that the jobs that would have been available to them would have been the same low-paying unskilled labor open to all working women. Elite groups of highly educated females stayed home rather than do the type of work larger numbers of lower-middle-class and working-class women were doing.”

Lesbian women were among the first to bring the issue of class to the forefront of the feminist movement. In embracing female partners these women compounded their experience of social inequality since they could not rely on a husband for economic support and security.

In Where We Stand: Class Matters (2000) hooks wrote that her earlier works centered on gender or race, but that she chose to begin with class now

“because I believe class warfare will be our nation's fate if we do not collectively challenge classism, if we do not attend to the widening gap between rich and poor, the haves and have-nots. This class conflict is already racialized and gendered. It is already creating division and separation. If the citizens of this nation want to live in a society that is class-free, then we must first work to create an economic system that is just. To work for change, we need to know where we stand.”

hooks recognized the seriousness of racism and sexism as forms of institutionalized oppression. Yet she also drew our attention to the comparative invisibility of classism even as it manifests itself before our very eyes. She contends that classism is harder to see and identify than sexism and racism. She wrote,

“The evils of racism and, much later, sexism, were easier to identify and challenge than the evils of classism. We live in a society where the poor have no public voice. No wonder it has taken so long for many citizens to recognize class—to become class conscious.”

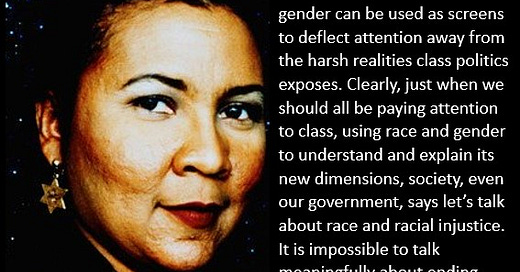

Class-based analyses fail us when they don’t account for the unique but interlocking harms of sexism, homophobia, and racism. Analyses that leave out class, argued hooks, are equally incomplete. “Class matters. Race and gender can be used as screens to deflect attention away from the harsh realities class politics exposes.”

hooks warned us that the very centers of power are often willing to lean into condemnation of racism and sexism to divert our attention from economic exploitation and inequalities. She wrote:

“Clearly, just when we should all be paying attention to class, using race and gender to understand and explain its new dimensions, society, even our government, says lets talk about race and racial injustice. It is impossible to talk meaningfully about ending racism without talking about class. Let us not be duped.”

Let us honor bell hooks memory by reflecting on our own economic-class privileges and also speaking candidly about our disadvantages. Let us refuse to equate dignity with economic power, and lift the voices of the poor among us to speak their truths, moving from margin to center.

If you enjoyed this post please share it with others and like it by clicking the heart icon. Be sure to subscribe if you haven’t already.

Invite Dr. Nall to Speak

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook or by leaving a comment.