We don’t always have our priorities straight, do we? Sometimes we pine for the presence of a loved one only to squander the limited time we have together. At other times we prioritize devices over the relationships they are meant to facilitate. There's even a word for the increasingly common social phenomenon of paying more attention to our phones than the people in our company: phubbing.

These behaviors and others like them are part of a broader cultural practice of prioritizing the means of life over the ends of life.

Just think of the common tendency to focus on photographing an experience more than being fully present during the experience. As I discussed in “The Joy in Not Taking the Photo,” we’re often motivated to photograph events as a way of capturing or preserving them. This is an understandable behavior given how porous and fleeting time is. But there’s something misguided about allowing our documentation of experiences to overtake being meaningfully present, organically, during the experience.

After all, the value of our photographs is rooted in their ability to trigger our memory and transport us back, virtually, to the experience itself. But what value does the photo have when it simply documents the fact we were too busy taking photographs to be present for the experience? What joy is their to recollect when we have traded that past opportunity to be joyfully present in life for a memento which now stands as an empty point of reference to an experience we were not present for?

While it’s probably not difficult to think of others who are guilty of losing sight of what is most important, the truth is that we’re all susceptible to inverting proper priorities—concentrating on the means before the ends. Consider the tendency to prize grades and grade-point-averages over the knowledge they are meant to symbolize. Some parents would be more proud of a child who earned an “A” but learned very little, than a child who earned a “B” but learned quite a lot.

What examples come to mind of people inverting priorities or forgetting the ends of life? Let us know in the comment section.

Or take our inclination to prioritize the possession of certain material goods that enhance our image over expending time and effort to more fully become what we wish to be. Don’t we sometimes invest more of ourselves in portraying a particular kind of ideal than authentically exemplifying it? To what extent are we disloyal to that powerful Latin motto, Esse quam videri, meaning, "to be, rather than to seem”? Such a vision of integrity runs in radical opposition to a consumer culture that encourages purchasable images and identity over the largely inward endeavor of authentic character development.

Rather than emphasizing being, consumer culture offers us short-cuts to illusory fulfillment that come at the expense of the genuine ends of life, the parts of life of ultimate importance. Matters are made worse by the fact that so many of us are overworked, usually underpaid, and mentally and/or physically exhausted. It doesn’t help that much of the work many of us have to do is boring and tedious, leaving us all the more tired and under-stimulated. And this is to say nothing of the fact most of us are expected to suspend our autonomy at work. When we clock-in, we are largely subject to someone else’s dictates and denied a meaningful say in how our workplace is organized and operated. Under these circumstances, the fraudulent joys of numbness, passivity, and automation become deceptively alluring.

The humanities are in open revolt against precisely these hollow stand-ins for the true joys of life. We are called to reject passivity and resignation, be it a lack of drive to grow and develop as individuals, or passivity and conformity in relation to the dominant culture and political structures of society. Being human, at its best, means being conscious, creative, and autonomous in living. We see such intentionality in individual efforts to make more principled choices and in the exercise of political agency by ordinary people forming unions in workplaces like Starbucks and Amazon.

The Fallacy of Forgetting Ends

Living well requires us to recognize the absurdity of prioritizing the means of life over the ends they are meant to serve. Means derive their value from serving ends, our foremost concerns or interests. This is why they are literally pointless when cut off from ends. Yet we go on fallaciously inverting the means and ends of life: mistakenly presuming that every being, endeavor, insight, or experience in life must “turn a profit” or be instrumentalized for some still further off gain.

This fallacy of forgetting the ends is the failure to recognize that some parts of life are purposes or ends unto themselves. They require no justification; rather, they give meaning or worth to those other purely practical endeavors in life. The kiss, the loved one, enjoying the natural world, experiencing personal growth, encountering beauty, exemplifying autonomy, and so forth are priceless features of human existence that transcend functional or transactional value. The ends are potentially useless yet simultaneously the source of usefulness itself.

Getting Our Priorities Straight: Honoring Ends

Many of the loudest voices demanding that we get our priorities straight actively direct us to deprioritize the ends of life. Consider, for example, those who not only advise young people to make wise choices to ensure gainful employment, but also insist that they must subordinate all other values to the single concern of choosing a career that affords maximum earning potential. Such supposedly “practical” advisors tell them to take up educational paths that, even if less intrinsically desirable, are most likely to lead to the most profitable of careers.

Given that most of us rely on work to make the money we need, it makes perfectly good sense to factor in likely earnings as we contemplate a prospective career path. But it’s another matter to insist we select our careers solely on the basis of the likely economic reward. This kind of thinking flagrantly exemplifies the fallacy of forgetting ends: prioritizing so-called practical concerns and activities over the very purpose—the ends—those practical activities are intended to serve and advance.

What do you think is a better measure of human success than salary and job title? Let us know in the comment section

This is the kind of fallacious thinking committed by those who argue that students majoring in the humanities and liberal arts do not have their “priorities straight.” The strict purpose of a college education, they contend, is to prepare students for not just gainful employment but maximum earnings. Such critics admit that students may have to sacrifice passion or enthusiasm in pursuit of greater earning potential, but the trade-off, they uncritically presume, is always worth it. And to the extent quality of life is factored in at all, it is narrowly oriented around economic well-being.

Students of the humanities who are knowledgeable of the means-ends distinction, however, recognize that the matter is not so clear-cut. Money is only valuable as a means to—a stepping stone—enabling us to pursue and experience the ends of life—the intrinsically good. Without enough money we may face a lack of basic needs along with lost opportunities to delight in those priceless experiences. Yet we must also consider the costs of over prioritizing money-making in our lives.

How might pursuing a career or taking a position that makes the most money take us away from the activities, experiences, ways of being, or manner of living that fulfills our ultimate values? Might we end up needing to make more money to “buy back” the joys we might otherwise have had woven into our daily lives through a preferable career? How might a position that pays less enable us to do a job that is not only a means-to-an-end but an end-unto-itself? Upon serious reflection of our foremost values, reason would dictate that many of us would be better off adjusting our material demands and lifestyle so that we could do work we were intrinsically motivated to do and satisfied doing. Above all it’s necessary to realize that these kinds of decisions turn on much more than simple matters of fact, they turn on value-based judgments that require us to distinguish between means and ends.

The Art of Living

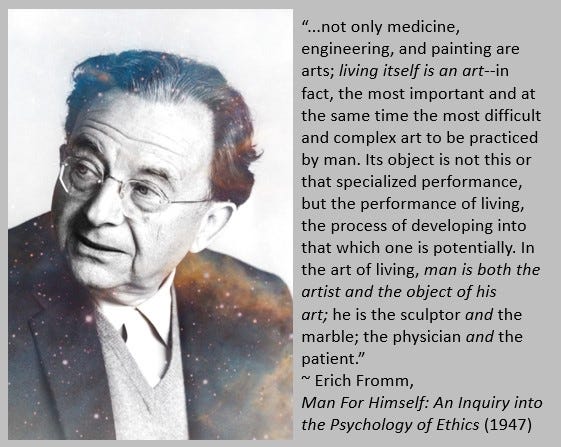

We all know that it requires great skill to fly an airplane or conduct surgery. What is less well understood is that living a good human life also requires skill. In Man For Himself: An Inquiry into the Psychology of Ethics (1947), the social psychologist and philosopher, Erich Fromm, eloquently summed up what it means to understand life as an “art”—a skill— when he wrote:

“...not only medicine, engineering, and painting are arts; living itself is an art—in fact, the most important and at the same time the most difficult and complex art to be practiced by man. Its object is not this or that specialized performance, but the performance of living, the process of developing into that which one is potentially. In the art of living, man is both the artist and the object of his art; he is the sculptor and the marble; the physician and the patient.”

Human beings are filled with potential, but this potential is not realized through passivity or resignation. Fulfilment, Fromm reminds us, does not simply “come to us” nor can it just be "given to us. It is, rather, an achievement resulting from knowledge and effort.

The humanities teach us that this art of living requires us to understand and implement keen discernment of the difference between the means and ends of life. Living well is not just a matter of how to do things in life. We must know what is worth doing. Specifically, we must discover what in life is valuable or important for its own sake. The answer to this question is the answer to the meaning of life question. When we know the ends of life, we are then in the position to begin strategically deploying our efforts—our how-to—in the service of those foundational values or principles that enliven all other aspects of our life.

Services

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook.

Subscribe

Subscribers will receive periodic posts pertaining to the broad domain of humanistic inquiry, from the insights of great thinkers throughout human history, the meaning and importance of critical thinking and ethics, the underappreciated poetry in everyday existence, to contemporary cultural analysis and the ongoing struggle to combat human oppression and violence. You will also have the opportunity to engage the author and our online community in dialogue about each post.

Why get a paid subscription?

Paid subscriptions directly support Dr. Jeffrey Nall’s efforts to produce and share publicly accessible independent scholarship and analysis. Supporting donations can also be made through PayPal. For more about my work go to JeffreyNall.com and find me on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.