Giving Veterans More than "Thanks"

Part I of a series exploring the intersection of movies and the military

This is the first part of a series of posts exploring the humanities, popular culture, veterans, and warfare. This is an expansion of a prior post and sets the stage for subsequent exploration of the contrasting the realities of many veterans in the military with popular representations of military service.

The Meaning of Our Thanks

In the Fall of 2021, I entered my small introduction to humanities class and asked students to take seven minutes to silently reflect upon and answer the following questions:

What do people mean when they tell veterans and current members of the military, “Thank you for your service?”

Is the message usually delivered meaningfully?

If you are a veteran, do you feel that this “thanks for your service” is usually said with authenticity, or is it usually said, superficially? Do you think people care or understand the ‘service’ they are thanking you for?

The class session that day was devoted to exploring the meaning and function of culture. Culture is that living repository of thought, belief, and often ritualized practice that shapes and defines much of our lives. The humanities help us critically evaluate culture. In doing so we become active participants in culture rather than passive recipients and promulgators of unquestioned beliefs, values, and practices. The humanities help us deepen understanding of ourselves and our own society—our thoughts, values, and way of life—as well as others around the world.

One of the powers of popular culture is that it can render an idea or behavior so ordinary that it is invisibilized: taken so much for granted that we don't even consciously notice it. The humanities reminds us that we are perfectly capable of inauthentically parroting a popular cultural expression or ritual without considering its genuine meaning, implications, or whether or not we sincerely relate to it in the first place. It’s just something we say, do, or accept.

On most days I would have asked students to reflect on the meaning of saying something like “bless you” after a person sneezes. (The answers are always as fun to entertain as they are revealing of how little we sometimes think of what we say and believe). Whenever I get the chance, however, I try to relate the subject and ideas I am teaching to the human beings in the classroom. And I knew that there were a few veterans in the class. They had shared this background with me and their colleagues in their class introductions. I figured the question of the meaning and sincerity of our thanking veterans for their service might provoke dialogue and debate as well as get us thinking about the influence of culture in everyday life.

The spontaneous responses that followed—particularly the responses from the sole combat veteran in the classroom—inspired a deeper awareness of the contradictions between the lived experiences of our veterans and our popular culture’s simplistic celebration of war and military service.

Exchanging Pleasantries for Authentic Dialogue

“I don’t even like to say I’m a combat veteran. I don’t even like to say I’m a veteran.”

These were the words of the sole combat veteran of the class. Given the near universal adulation for the military and veterans in our nation this may seem like a strange reaction. Why wouldn’t he proudly claim his veteran and combat veteran status? Aren’t our veterans routinely described as bonified “heroes”? His answer boiled down to this: he wasn’t convinced most people really wanted or cared enough to understand the complexities of his military experience. As he spoke two more hands in our small class darted up.

The next student said he understood why his colleague didn’t like identifying as a combat veteran. He explained that his brother, who was serving in the military at the time, disliked the empty flatteries soldiers are showered with. The praise didn’t comport with the traumatizing conditions and the moral ambiguities that characterized his experience. How could they when, according to the civilian brother, some of what he was asked to do as a soldier felt wrong. How might we feel if thanked for actions we believed were misguided or immoral?

A third student explained that she understood what her classmates were talking about. She said her stepfather, who fought in the Vietnam war, didn’t like talking about his experience in the military. She sees the pain and discomfort in his eyes when people ask insensitive questions like, “So, did you kill anybody over there?” “How many did you kill?” Missing from such questions is the basic awareness that killing another person is always a traumatizing experience to a healthy and humane person.

We get a sense of what is glaringly absent from popular media portrayals of war by listening to Vietnam war veteran, W.D. Ehrart, describe the drastic distance between the realities of his actual experience as a combat soldier, and the expectations he derived from prominent media narratives he encountered before going into the war.

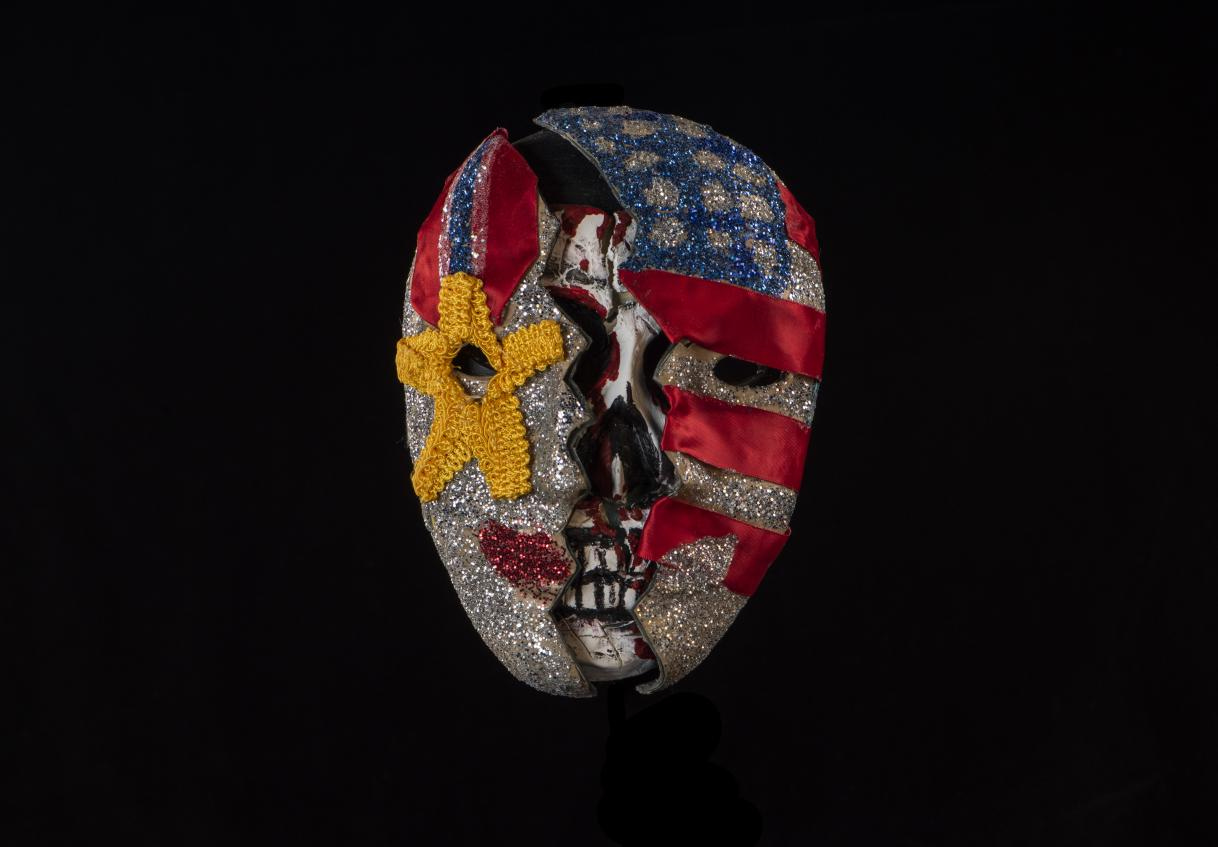

The National Endowment for the Arts eclectic interactive exhibition, "Creative Forces: Healing the Invisible Wounds of War” highlights the healing power of the humanities for veterans, and gives us a unique, intimate window into veterans’ experience with war. One of the works, “Bronze Star,” was created by an army soldier to represent his military service. According to the exhibits description:

"The mask portrays the Bronze Star medal he received for heroic action in combat and a glittering American flag which folds open to reveal a haunting skull underneath. The interior of the mask reveals, he said, ‘the evils of war that mortally wounded my soul, pieced and held together by past hopes, dreams, and happiness with loved ones that no longer exist the way they did before war's horrors.’”

This is not to say that all soldiers share such feelings. Two of the veterans in the class spoke more favorably about their experience in the military. Both men were proud to identify as veterans and spoke well of the opportunities for adventure and personal and professional growth. It’s also worth noting that neither had seen combat, reminding us that not all veterans have the same military experience and not all veterans assess their experiences the same.

A veteran from a different class, during the same semester, wrote about his struggle with alcoholism in the wake of his service. “As a medic, and through my military service, I have seen awful things,” he explained. “In order for me to get sober and remain that way, I had to address some demons that were very deep inside, that I had intentionally buried for the sole purpose of never being found.”

Students of all backgrounds, including veterans, often find consolation in the humanities’ acknowledgment of the often overlooked difficulty of simply living; of living a up to social-cultural expectations, of living authentically, of identifying and exemplifying excellence. Great thinkers such as the Roman Stoic philosopher, Seneca, honor the difficulties of life while also challenging us to devote the time and thought necessary to learn how to live well. In “On The Shortness of Life” (49CE), Seneca wrote:

“There is nothing the busy man is less busied with than living: there is nothing that is harder to learn. Of the other arts there are many teachers everywhere; some of them we have seen that mere boys have mastered so thoroughly that they could even play the master. It takes the whole of life to learn how to live, and—what will perhaps make you wonder more—it takes the whole of life to learn how to die” (Chapter VII).

That living well is the result of knowledge and effort—skill—is itself an empowering idea, reminding us that human growth requires the assertion of intentionality, agency, and a daring to examine even that which is most familiar and precious to us.

Humanities courses like mine deal with big, real-world questions of how to live and what to live for. We explore everything from human mortality and the meaning of life to critically examining the way military service is portrayed in popular media such as movies. I also make myself available to listen to and learn from my students. Together, these questions and conditions invite dialogue about experiences and truths that fail to fit into the dominant, neatly produced cultural narratives. This is how it happened that, in 2022, a Marine veteran educated me about some of his unique experiences in the service.

In addition to dealing with a physical injury that occurred during his service, and the questionable care he said he received from the military, he has also seen many of the soldiers he was deployed with struggle with suicide. To his credit, he has made it a mission to proactively seek out mental health care for himself and encourage fellow veterans to do the same. While he praised the care he received following a colleague’s suicide, he believes the military should do a better job of offering preventive care and better preparing all soldiers to return to civilian life.

Understanding and Civic Responsibility

Dominant U.S. culture has made it easy for us to express our “thanks” to veterans and participate in self-congratulatory ceremonies of praise for our “heroes.” There is far less cultural space afforded to us to listen, understand, and come to terms with the kinds of experiences described above.

Being reflective and honest we have to admit that some of the “thanks” given to veterans are empty “patriotic” platitudes. As the veteran studies scholar, Eric Hodges, himself a veteran pointed out in his 2013 Ted Talk, vague statements of praise without genuine consideration of what it means to be a veteran can contribute to soldiers feeling even greater alienation in civilian life. For there to be genuine meaning in our thanks there must be some depth of understanding. To this point, veteran Jake Wood adds,

“The health of our all-volunteer force rests on our nation's ability to understand what life in the military and at war entails. A poor understanding leads to poor policy decisions—both during peace and during war.”

Pursuing a genuine understanding of war would force us to deal with moral complexities and civic responsibilities many of us have grown accustomed to pushing to the side. Taking this step requires us to do more than “thank” veterans; it requires us to attentively and empathetically talk with them about their experience. When it comes to matters of war and peace, we should exchange pleasantries for genuine listening and conversation. And we should never lose sight of the fact that we are ultimately civically responsible for sending our men and women in uniform into combat. This responsibility should never be taken lightly or allowed to drift too far from our minds as we carry out our duty as citizens in a free and democratic society. Passing praise, in short, is no substitute for genuine dialogue and earnest critical reflection.

If you enjoyed this post please share it with others and like it by clicking the heart icon. Be sure to subscribe if you haven’t already.

Invite Dr. Nall to Speak

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook or by leaving a comment.

Wikipedia writes about U.S. military veterans and their high rates of suicide:

"A 2021 study by Brown University estimated that 30,177 veterans of post-9/11 conflicts had died by suicide. When compared to the 7,057 personnel killed in the conflicts, at least four times as many veterans died by suicide than personnel were killed during the post-9/11 conflicts.[10]

"According to a 2022 report by the Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, nearly half of U.S. military service members have seriously considered suicide since joining the Armed Forces.[11]"

Now, perhaps the problem is war itself; perhaps it is not normal or healthy for one human being to kill another human being for no reason other than he or she is another nationality or religion or political affiliation or for whatever reasons humans engage in war, such as the needless taking of land, resources or to increase the profits of the War Industry.

All of this and the many other reasons I have not cited combine to make being a military veteran an unhealthy choice.

Thank you for this. My partner is a combat veteran who suffers from PTSD. I cringe when I hear the hollow "thank you for your service" quip tossed casually in her face. I rank it up there with saying "everything happens for a reason" to someone deeply suffering a loss. However well meaning, it's still flippant, casual cruelty.