How to Train Your Dragon and Liberate Men

What Hiccup and Mr. Rogers Teach Us About Real Strength and Humane Manhood

As a boy Fred Rogers, believed being “strong meant having big muscles, great physical power.” Over time, the boy who became a pioneering children’s programing creator best known as Mister Rogers came to “realize that real strength has much more to do with what is not seen. Real strength has to do with helping others.” This was a vision of strength that Rogers went on to consistently convey through the more than three-decade run of his half-hour children’s show, Mister Rogers' Neighborhood.

Despite Mr. Rogers’ best efforts to guide American culture toward reconceiving human empowerment as centered on self-knowledge, emotional awareness, and love, the idea that strength means “big muscles” and physical dominance lives on. This misunderstanding of strength is especially influential in (mis)informing widespread and deeply entrenched ideas of what it means to be a man.

Still, Mister Rogers’ cause of subverting an equally ancient and destructive vision of power and replacing it with a life and love-affirming vision, has not yet been fully lost or abandoned. Today, we find this revolutionary banner taken up once more in the deceptively unassuming medium of children’s programing. One such example is the film How to Train Your Dragon (2025).

Men are Made for War

Dominant culture continues to identify manhood and masculinity with violent social roles. The psychiatrist, James Gilligan argues that within patriarchal society women have been treated as “sex objects” while men have been assigned the role of “violence objects.” In practice this means that children are taught that their self-worth as women and men will be determined by certain functions rather than virtue of their inherent humanness.

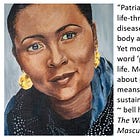

“When I was a boy I used to think that strong meant having big muscles, great physical power; but the longer I live, the more I realize that real strength has much more to do with what is not seen. Real strength has to do with helping others.” ~ Mr. Rogers, The World According to Mister Rogers (2003)

Girls and women learn that their worth falls or grows in proportion to their attractiveness or desirability. Historically, boys and men have benefited from this cultural ideal of female worth by being the ones who get to assess girls and women’s desirability and thus determine their worth.

But this male privilege has long come with a fine print: male worth is contingent on the capacity to control if not outright dominant, defeat, or even destroy others through force. And men’s demonstrations of dominance are to be done at the command of others and silent yet forceful social expectations rather than their own conscience.

“Masculinity, in the traditional, conventional stereotypical sex-role of patriarchy,” writes Gilligan, “is literally defined as involving the expectation, even the requirement, of violence, under many well specified conditions: in time of war; in response to personal insult; in response to extramarital sex on the part of a female in the family; while engaging in all-male combat sports…..” Though some will dismiss this view as “feminist propaganda,” evidence isn’t difficult to find.

The objectification of men as violence objects is demonstrated by the fact that only males are required to register for the selective service in the United States. Selective Service enables the government to choose them for military service in the event of a draft. Males between the ages of 18 and 26 must register or face a variety of penalties including loss of government sponsored funding for college, paying fines, or even serving prison time. In December 2024, President Joe Biden signed the 2025 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) into law, which included a provision automating registration for selective service.

That men are uniquely expected to fulfill violent social roles was made clear when the suggestion of some lawmakers that adult women in the U.S. also be automatically entered into the selective service and thus eligible for the draft was met with vociferous criticism. Republican lawmakers successfully removed a provision from the 2025 NDAA that would have required women to be registered for selective service. “Forcing young women to register for the selective service is an affront to our nation’s values and does not enhance military readiness – the only metric by which Congress should measure an NDAA,” read a statement from 22 representatives. “This is yet another blatant attempt to advance a divisive agenda that seeks to eliminate all distinctions between males and females.”

Hiccup’s Revolt: Empathy and the Refusal to Kill

Those who think linking masculinity to violence is narrow and dehumanizing will find inspiration in the live action movie, How to Train Your Dragon (2025). At the start of the story, the protagonist, a Viking boy named Hiccup, tries to meet the conventional masculine expectations of his family and society. Despite his best efforts to be as strong and intentionally violent as required, he just can't cut it. In fact, one of the best young warriors is a girl. (It's noteworthy that not only boys and men but also girls and women strive to achieve the masculine ideal since those who do so are often honored and even rewarded in society. There is money to be made and power to be gained by those who subdue moral concern for others and follow orders.)

Hiccup’s empathy thwarts an easy chance to achieve a rare and glorious kill. Standing face to face with an elusive night fury dragon, one who is immobilized and vulnerable, Hiccup knows this is his chance to prove himself by going in for the kill. Even the dragon knows it, closing his eyes awaiting the death blow. But Hiccup’s respect for life is too great and his resolve to kill is too weak.

Initially, Hiccup feels like a failure. In a society where violence is a revered form of labor, empathy is viewed as a kind of disability. Hiccup's sensitivity to life is viewed as antithetical to being a “real” man, someone capable of great strength and moral suppression.

Mister Rogers, who was an Presbyterian minister, observed that most people tend to “admire strength.” Our mistake, he suggested, was in confusing “strength with other words—like aggression and even violence.” Hiccup’s world is like ours in that it admires strength and conflates it with the capacity for dominance.

Still striving to prove his manhood, Hiccup uses his newfound relationship with a dragon—“Toothless”—to successfully advance in his community’s coming-of-age dragon fighting program. Hiccup is able to use his knowledge of dragons—that they are sickened by eel, for example—to harmlessly repulse them in the training, all while projecting violent mastery over the dragons.

Hiccup’s subterfuge is soon discovered. He’s revealed as a “fraudulent” warrior. A society that has placed its faith in dominance is not easily swayed to realize the power of connected knowing. Especially painful to Hiccup is the disappointment his father feels. The story reminds us that, as much as boys may contend with their fathers, they are usually trying their best to prove themselves worthy of paternal love. Too often this love is contingent on the performance of a “strong” or outright violent masculinity; in Hiccup’s case, a way of being that is incompatible with who he really is.

What is often missed in contemporary discussions of cultural expectations of males and females is just how few of us actually fit into the stereotyped cultural boxes of conventional femininity and masculinity. Those who fit within the boxes have usually sacrificed a great deal of integrity to so that they may feel worthy of love.

How to Train Your Dragon teaches us of just how much we have to learn from those who cannot or simply will not constrain their humanity to be model men. Hiccup's subversive empathy and knowledge of the other—the dragons—becomes a vital asset for actually solving his community's long-running struggle to protect themselves from the dragons. For the dragons like so many men are driven to violent behavior by existential desperation, not an intrinsic desire to destroy. Their mistake—the dragons and the men—is believing they have no choice but to obey those with the most muscle.

By the film’s end, Hiccup proves that there's more than one way to be a man and there’s more than one way to be “powerful.” Being the kind of man who exerts himself in the world through knowledge and love may well be the most glorious form of manhood of all.

❤️ Like,🔄 Share, and✊ Subscribe

Read more of our work on men, manhood, and masculinity

“What is often missed in contemporary discussions of cultural expectations of males and females is just how few of us actually fit into the stereotyped cultural boxes of conventional femininity and masculinity.”

I contend that much of the anxiety and suffering is due to Western cultural preferences for dualistic thinking and the artificial creation of static “roles” while ignoring the underlying continuum of energy flows. Our psyches, our souls are fluid and dynamic which causes tension and anxiety when inhibited and boxed in.

I find the Asian concept of the balance of assertive ‘yang’ and receptive ‘yin’ energies to be more “Mr. Roger’s-like” and authentic. Capacity to find our individual energetic center point and to freely move to the appropriate level of yin or yang response feels natural and freeing. One soon realizes the fearsome “dragon” is actually a mythological characterization of our existential anxiety at not being allowed to appropriately respond to threats either real or perceived.

Yes, hormonal differences will naturally set our center point, but we all retain a full range of yin-yang energetic responses. We all know not to confront a momma grizzly bear and her cubs. A natural full flow of assertive yang response is guaranteed. And, yes, we can be culturally trained or “tamed” to fulfill certain roles in society, but true power and grace is achieved by finding our personal energetic neutral point and allowing the freedom to respond instinctively to our environment.

That is how, not so much to “tame” our dragons, but to trust and free these life energies to achieve their sacred purposes. Then, both men and women can feel “liberated.”

Sweet article. I will share. Too bad it isn't getting more exposure, but that is the way it is for men. If it were two million women instead of men dying in Ukraine, the war would have ended a long time ago, or never started at all. If women died an average of six years before men, there would be pink ribbon marches every day. But men live with a conspiracy of silence.