My Humanities Journey

Excerpt from "Getting Our Priorities Straight: Humanities and the Art of Living" (Sunday, March 19, 2023)

The following is an excerpt of the remarks I will deliver on March 19, 2023 for the Unitarian Universalist Fellowship of St. Augustine.

The path to my teaching vocation is a bit different from many of my colleagues in academia. I was nothing more than a very mediocre student throughout my youth and dropped out of high school in my senior year. Thirteen years later I earned a doctorate in Comparative Studies from Florida Atlantic University. And I regret nothing.

I actually view dropping out of high school as one of my earliest experiences of autonomy. This definitively agentic decision began a shift in my thinking about what was possible and permissible. Up to that point I experienced schooling as largely tedious, lifeless, automated, and narrowly conceived. Something others did to me without consultation; something I endured with the goal of perfunctory completion rather than growth and enthusiasm.

I would later learn that a long list of great thinkers—from Emerson, Thoreau, Emma Goldman, Jack London, Albert Einstein, Maria Montessori, Bertrand Russell, Erich Fromm, Paul Goodman, Abraham Maslow, Ivan Illich, to Howard Zinn, Noam Chomsky, and bell hooks—believed that the dominant system of schooling failed to cultivate and even undermined critical thinking, creativity, anti-authoritarian and democratic values; that it alienated learners from their natural intellectual capabilities and undermined the joy of learning. I was surprised to learn just how many great thinkers vehemently objected to schooling's emphasis of didactic learning, competition among students, grades, and accumulating information over self-discovery, dialogue, imaginative exploration, and passion-inspired inquiry. And all this criticism before the rise of teaching to the test.

As an aspiring writer I also found it intriguing to learn that creative figures like Mark Twain had little formal schooling. Twain and London were both school dropouts, making it deliciously ironic that each man should have schools named after them. Twain left school after fifth grade while London left school to work at age 14.

We get a sense of London's view of the dominant schooling curriculum of his day from his innovative science fiction novel, Iron Heel (1908). The book tells of the rise of the “Oligarchy” or “Iron Heel” in North American during the early 20th century, and the thwarting of the first revolt against their fascistic takeover of the United States. The story is told through an incomplete manuscript, written by revolutionary Avis Everhard in 1932, and a scholar, Anthony Meredith, who discovers the text in the year 2600 AD, 400 years after the eventual defeat of the Oligarchy. We read of a book banned by the Oligarchy that described

“the capitalistic bias of the universities and common schools. It was a logical and crushing indictment of the whole system of education that developed in the minds of the students only such ideas as were favorable to the capitalistic regime, to the exclusion of all ideas that were inimical and subversive.”

Twain never returned to formal schooling, while London returned at age 19 to complete a four-year high school program in less than two years. London began studies at the University of California, Berkeley, but eventually abandoned college and committed himself entirely to writing.

In fairness to the Mark Twain High School of Missouri, Twain was a staunch advocate of free and accessible schooling for the wider public; and the Jack London Continuation High School’s mission of offering students with troubled schooling experience a “peaceful,” “project-based,” and “personalized” school experience is not at all incongruous with London’s ideas of education. Yet one wonders how much the school challenges the capitalist bias London thought dominated schools of his day, or if they freely disclose London's lifelong commitment to socialist values and politics. I couldn’t find any such mentions on the school's website, but I may have overlooked them; perhaps all students are issued a copy of Iron Heel upon being admitted.

The more important point is that these two great American writers and thinkers teach us to disentangle the ideas of “schooling” and “education.” Schools are not the only means to education. Twain and London were steeped in the works and ideas of great thinkers and works of the humanities. They procured this education through life-experience, experimentation, and concentrated, serious study, much of which was made possible by public libraries. Formal schooling was a minor factor in their education.

Disentangling learning from school was important for me because I wanted nothing to do with school. As someone who probably had—and still has—undiagnosed dyslexia, I particularly disliked reading. I recall being admitted to an honors English course in high school only to obstinately refuse doing the assigned reading and assignments. I failed the class miserably and was undoubtedly a nuisance to the teacher.

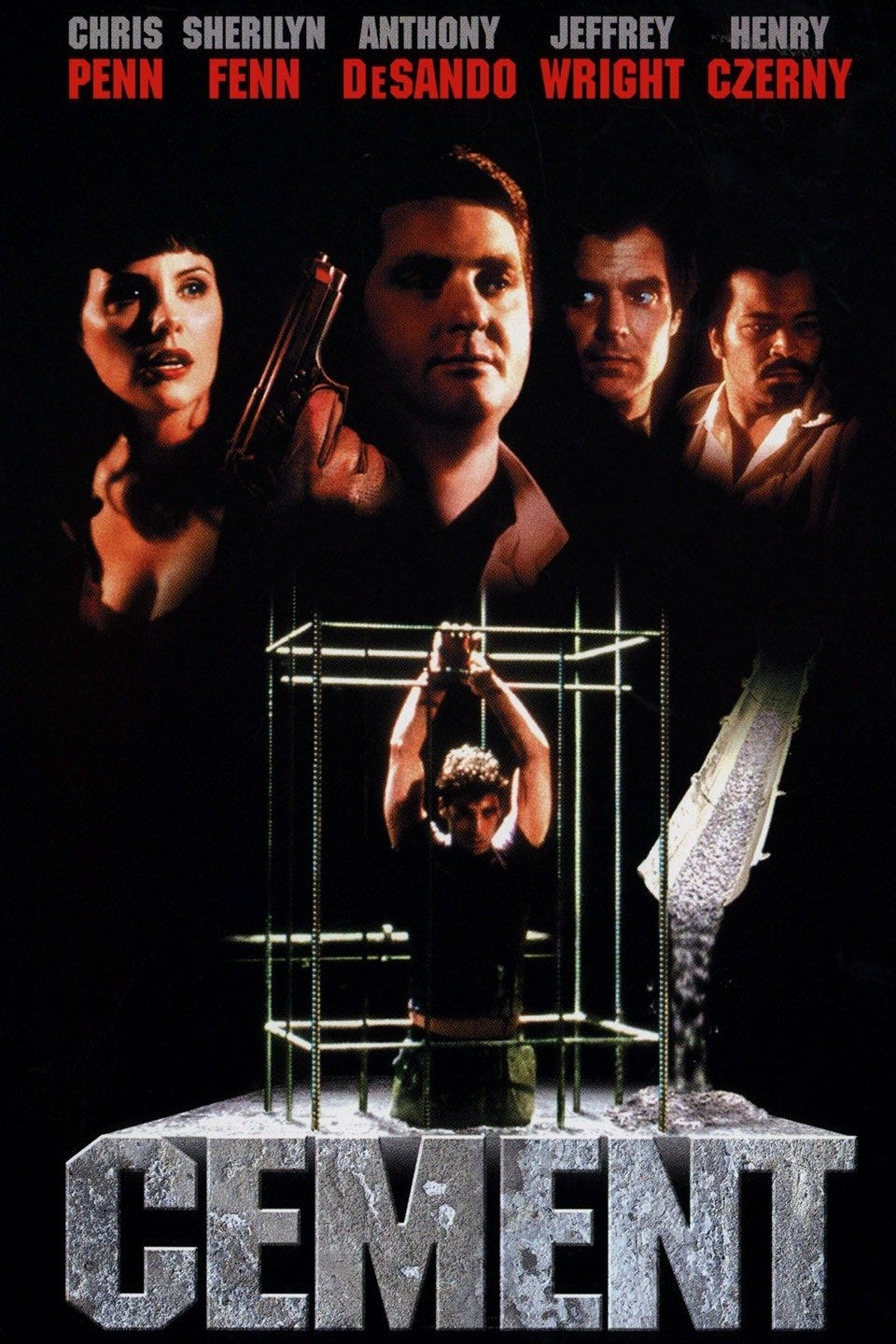

My children find this history strange. It does not comport with the reality of living in a small home made all the smaller by their father’s myriad tomes squeezed onto buckling bookshelves; and the fact hardly a table or flat surface is unadorned by a dog-eared and scribbled in book. My love of reading began when I left school and took a 72-hour Greyhound bus ride to Los Angeles to work as a minimum-wage production assistant on the movie, Cement.

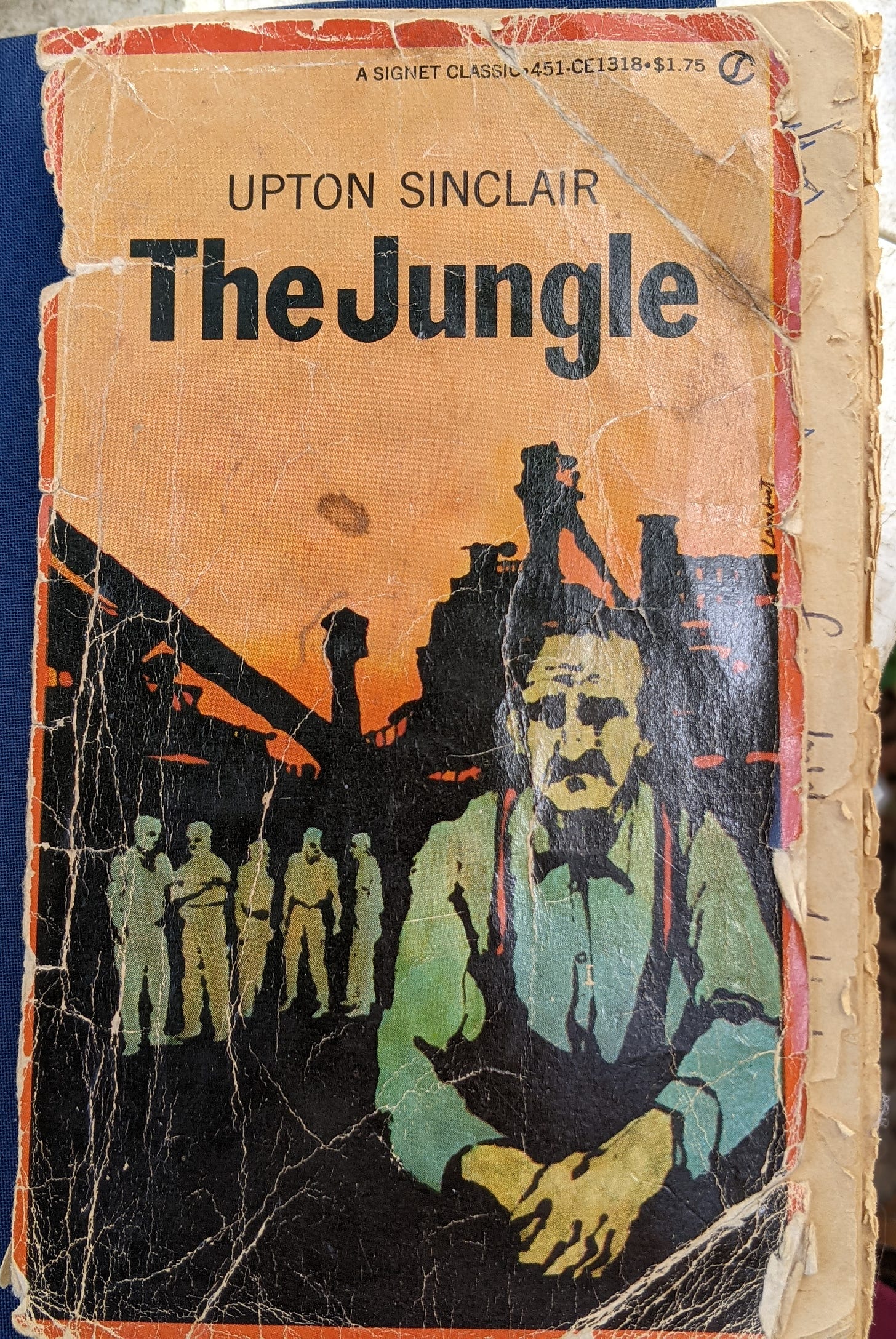

I was an 18-year-old with an abysmal GPA somewhere around 1.7 out of 4. Before I left I met with my high school journalism teacher. He knew I wanted to be a writer and advised me to read as much as possible. He also gave me a bundle of books including Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle and J.D. Salinger The Catcher in the Rye. I was and still am a slow reader. When I wasn’t running errands for the movie makers—script drop-offs to actress Sherilyn Fenn, running canisters of the day’s film to be processed, or bringing processed film to director, Adrian Pasdar's home in the Hollywood Hills—or calling companies to get freebee soda, beer, or a cement mixing truck—I would read. I spent half the time looking up words—without the advantage of a smart phone or Google. Twenty-five years later, I still have the copy of The Jungle my journalism teacher gave me. A 1960 Signet Classics edition. The back of the cover is crisscrossed with a cacophony of diagonally written words like “incredulous,” “dubious,” and “obdurate.” Vocabulary words, if you will.

My relationship with formal education changed after I returned home to south Florida and passed the GED (General Educational Development) test. I enrolled in what was then Miami Dade Community College with the intent on completing a two-year degree in film. Then I encountered philosophy—“ethics,” to be exact.

The radically open and imaginative yet temperate exchange of ideas was electric and enlivening. The environment exuded a “love of wisdom” I had rarely encountered in formal educational settings. And while I was lucky to grow up in a family where questioning and debate were normal, the philosophy classroom was different. Unasked questions were articulated; discouraged opinions were brought into open dialogue; uncomfortable contradictions were highlighted; and the beauty of creative, critical introspection was unshackled from conventional, common sensical expectations.

Virtually nothing was taken for granted as “self-evident” in the philosophy classroom. All political-moral beliefs were equally scrutinized; all methods of knowing were scrutinized in a rigorous manner. Yes, religious beliefs were critically examined, but so were the principles about universal causation that the entire field of science rests upon. There was a lot of listening and diverse perspectives were given ample space to stretch out to their fullest development. The aim wasn’t cheap victory—pot shots and drive-by zingers. The aim was understanding, exploration, and a disciplined pursuit of knowledge.

I’m being sincere when I say that it was then that I began to fall in love with wisdom. This led to a rather extended relationship with higher education: I went on to earn a BA in Humanities and Master of Liberal Studies from Rollins College before going to FAU for a PhD.

I began my teaching career at Indian River State College in the Summer of 2010, a year before finishing my doctorate. Since then, I’ve been sharing my love of ideas and belief in the power of the humanities to facilitate self-actualization as a professor in the college classroom. I’ve taught a variety of courses in philosophy, ethics, humanities, and gender studies. Though I learned a lot as a student, nothing has taught me more than crafting and teaching courses like “Freedom and Justice,” “Men and Masculinities,” “Sex, Violence, and Hollywood,” “Humanistic Traditions I,” “Introduction to Ethics,” “Creative and Critical Thinking,” and “Gender and Sport.” Putting ideas to the test, in dialogue with students, has been integral to my intellectual growth. That and being privileged to call “work” studying and discussing great ideas.

Along the way I’ve been a full-time father, civically engaged citizen, and public speaker. In my public speaking I’ve attempting to bridge the gap between the “ivory” tower and ordinary life. Scholars aren’t always the best at communicating ideas to a general public. And that’s a shame. Too many great ideas are obscured by the high walls of jargon and academic detachment from the elemental goal of life: living well and activating our fullest humanity. Flourishing, in a word.

In August of 2021 I began this newsletter with the aim of sharing some of what I teach with a larger public audience. Humanistic studies are too important to be confined to colleges and universities. And while it can be said that the humanities are all around us—music, movies, art, books, quotes from great thinkers, religion and the like—what makes the humanities different, as we practice them in higher education, is that the emphasis is on rigorous evaluation, critical dialogue, and patient contemplation.

I think it’s fairly obvious that these are not ordinary features of our engagement with ideas and the arts in daily life. For example, people routinely share great quotes via social media. But sometimes those quotes are misattributed to the wrong thinkers. For many these kinds of errors aren’t a big deal. But I think that if it’s important enough to attribute the idea to a thinker then we should make sure we’re attributing it to the right person. At times ideas are attributed to thinkers that run counter to the very ideas they advocated for in their time. More importantly, however, people often use these quote images as exclamation points—as nails in the coffin of dialogue, whereas a great quote, in a humanities classroom, is the beginning of a potentially lengthy period of reflection and discussion.

Read more: “Nietzsche Didn't Say That... But He Would've Agreed” and “Confucius Didn't Say That...Why We Shouldn't Rely on Quotes to Think and Speak for Us”

At their best, the humanities are about engaging with the great thinkers and works of art, philosophy, literature, religion, and taking time to dig into human history, to gain vital perspective on what it means to be human and what we know and what deserves to be called genuine knowledge. Such a bounty of questions, ideas, beautiful expression deserves to not only be more respected within the dominant educational institutions of our society, but also merits fuller inclusion in our ordinary lives. As my students report semester after semester, bringing the humanities’ humanistic lens to everyday cultural experiences deepens those experiences and enriches our feelings and thoughts.

Please share and like this post by clicking the heart icon.

Invite Dr. Nall to Speak

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook or by leaving a comment.