Self-Sacrifice is Not Suicide: Understanding Aaron Bushnell's Self-Immolation with Help from the Humanities

On February 25, 2024, Aaron Bushnell, a 25-year-old member of the U.S. Air Force walked to the Israeli embassy in Washington, D.C., poured the contents of a canister over his army fatigues, and lit himself on fire. He died later in the day from his self-inflicted injuries. Bushnell’s final words were “Free Palestine,” a statement he cried out at least six times as the flames consumed him.

Bushnell believed that the U.S. government’s support for the Israeli war in Gaza constituted complicity in “genocide.” The war has caused more than 30,000 deaths including more than 12,000 children and a currently unfolding famine. The morning of his death, Bushnell posted a message to Facebook that read:

“Many of us like to ask ourselves, 'What would I do if I was alive during slavery? Or the Jim Crow South? Or apartheid? What would I do if my country was committing genocide?' The answer is, you’re doing it. Right now.”

Bushnell’s death has further highlighted deep political divisions between those supporting Israel’s total siege of Gaza and those convinced the bombardment constitutes a clear case of genocide. Many commentators have expressed outrage and even disgust at the characterization of Bushnell’s inexplicable action as an instance of venerable self-sacrifice.

An opinion piece published in the New York Post, captured the perspective of many. Titled, “Reckless lefties celebrate Aaron Bushnell's suicide—and don't care if it prompts copycats,” the author wrote that Bushnell committed suicide and was self evidently “deeply unwell.” Robby Soave of The Hill's Rising show unequivocally characterized Bushnell’s action as an instance of “suicide.” The Atlantic’s staff writer, Graeme Wood, penned a piece titled, “Stop Glorifying Self-Immolation,” in which he castigates those “moved” by the self-immolation of Bushnell. “Self-immolation is a violent [act],” Wood wrote, “indeed one of the most violent, and if you dislike violence, then you should abhor it no matter your view on the war in Gaza.”

Such criticisms might be rhetorically useful in trying to stymy growing American discontent with the war on Gaza. But they rely upon superficial analysis and a false equivalency that fails to reflect deeper existential truths; truths too often absent from dominant media discourse. Here the humanities prove an invaluable resource once more, providing a humanistic context enabling a deeper, richer understanding of human affairs including the terrifying and tragic self-immolation of Aaron Bushnell.

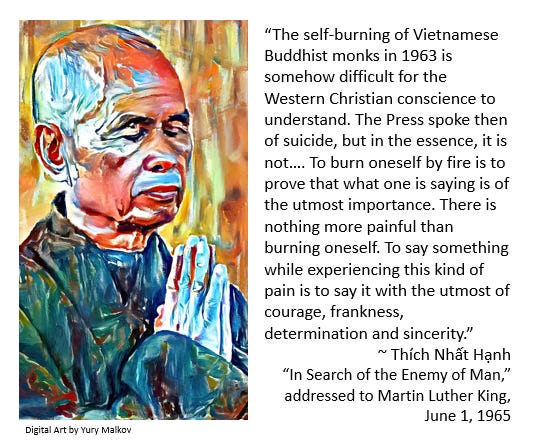

Specifically, we can find insight into the meaning of Bushnell’s act, and why it isn’t an instance of suicide, by turning to a 1965 letter written by a Vietnamese monk amidst the Vietnam War to an American Civil Rights leader. The Civil Rights leader was Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The monk, Thich Nhat Hanh, would go on to befriend King and work with him to advance the cause of global peace and human dignity. Hanh, who outlived his friend, dying at the age of 95 in 2022, became a world-renowned practitioner of Buddhism, pioneering a movement to bring the spiritual tradition into wider engagement with ordinary people, problems, and life.

A Plea for King to End His Silence

On June 1, 1965, Thich Nhat Hanh sent a letter to Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King titled, “In Search of the Enemy of Man.” It was the first communication between the two men. Hanh wished to rouse Rev. King’s conscience and inspire him into action for peace against the cataclysmic destruction of the Vietnam War. The war was causing “hundreds and perhaps thousands of Vietnamese peasants and children to lose their lives every day,” Hanh wrote to the 1964 recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, “and our land is unmercifully and tragically torn by a war which is already twenty years old.”

Having read of King’s efforts to combat segregation and oppose black people’s dehumanization, Hanh wrote that he was confident King understood and empathized with the suffering of the Vietnamese people. But that empathy needed to be expressed as open opposition to the war. “The world's greatest humanists would not remain silent,” Hanh wrote, referencing “religious humanists” such as Albert Schweitzer and Paul Tillich. “You yourself can not remain silent.”

King went on to heed Hanh's plea in the years that would follow the letter, culminating in the April 4, 1967 address, “Beyond Vietnam.” The speech, in which King called the U.S. government “the greatest purveyor of violence” and called for America to undergo a “revolution of values,” proved to be the boldest and most widely condemned of King’s high profile public speeches. It also represented the crystallization of his conception of injustice as a giant triplet of evil that entailed not only racism and economic exploitation, but also militarism. The subtitle of the speech, “A Time to Break Silence,” vividly recalled Hanh’s plea for King to join the unofficial interfaith alliance of humanists and end his silence on Vietnam.

Before delivering the “Beyond Vietnam” speech, King nominated Hanh, on January 25, for the 1967 Nobel Peace Prize. King wrote he was privileged to call Hanh a friend, and that awarding him the Nobel Peace Prize “would remind all nations that men of good will stand ready to lead warring elements out of an abyss of hatred and destruction. It would re-awaken men to the teaching of beauty and love found in peace. It would help to revive hopes for a new order of justice and harmony.”

Nearly one year after Hanh sent his letter to King, the two men met in Chicago and issued a joint statement titled “Buddhists and Martyrs of the Civil Rights Movement.” The statement read,

“We believe that the Buddhists who have sacrificed themselves, like the martyrs of the civil rights movement, do not aim at the injury of the oppressors but only at changing their policies. The enemies of those struggling for freedom and democracy are not man. They are discrimination, dictatorship, greed, hatred and violence, which lie within the heart of man. These are the real enemies of man—not man himself.”

Hanh and King were in solidarity in their commitment to the love of humanity. Their common enemy was not a particular group of people—the Americans or white people—but rather the corrupting beliefs, attitudes, and actions, all so much a part of the human condition, responsible for generating so much pain and suffering.

Their statement is a profound rebuke of the ad hominem—the personal attack—and an affirmation of reason and love in pursuit of justice. As Hanh initially expressed it in his letter to King, one year earlier, the self-immolating monks did not desire the death of even their oppressors. What they wanted was a change in policy and to combat cupidity, intolerance, and the other maladies outlined in their joint letter. “I also believe with all my being that the struggle for equality and freedom you lead in Birmingham, Alabama,” Hanh wrote, “is not aimed at the whites but only at intolerance, hatred and discrimination.” He added that he and his fellow monks were trying desperately to urge their brothers not to kill people: “Please kill the real enemies of man which are present everywhere, in our very hearts and minds.”

Hanh could not sleep the night he learned of King’s assassination. “They killed Martin Luther King,” he wrote to a friend. “They killed us.” Hanh described praying for King after learning of the assassination. Then it occurred to him that King did not need the prayer. “He does not need it,” he said to himself. “You have to pray for yourself. We have to pray for ourselves.” Hanh took comfort in the fact that he had told King that the people of Vietnam considered him a “bodhisattva,” an “enlightened being trying to work for the emancipation of other human beings. He did not say anything but I knew he was so moved by what I said.”

The Meaning of Self-Immolation

The bond of humanistic love between Hanh and King was forged in the contemplation of the fiery sacrifice of self-immolation. Hanh’s letter, “In Search of the Enemy of Man,” began with the observation that the Western media did not understand the Vietnamese monks who took action to challenge dehumanization, namely the suppression of Buddhism by the U.S-backed regime in South Vietnam. Multiple monks were inspired by the example of Buddhist monk, Thich Quang Duc, who self-immolated in the middle of a busy intersection of Saigon on June 11, 1963.

The American press inaccurately characterized their acts of sacrifice as “suicide,” explained Hanh. In words as applicable to Graeme Wood and other mainstream commentators writing today about Bushnell as they were to the U.S. media of the 1960s, Hanh wrote,

“The self-burning of Vietnamese Buddhist monks in 1963 is somehow difficult for the Western Christian conscience to understand. The Press spoke then of suicide, but in the essence, it is not….”

Suicide entails a desperate abandonment of life, Hanh explained. Those who commit suicide often do so out of a “lack of courage to live and to cope with difficulties,” or felt a “loss of hope,” while some even wished to escape existence itself. Such were not the motives of self-immolating monks.

It's true that self-immolation and suicide share the commonality physical “self-destruction” and the ending of a life. The difference of intent is what makes for a profound conceptual distinction between suicide and self-sacrifice. Though their act was self-destructive, the Buddhist self-immolators were not motivated to end or evade life. On the contrary, they wanted life to flourish.

“The monk who burns himself has lost neither courage nor hope; nor does he desire non-existence. On the contrary, he is very courageous and hopeful and aspires for something good in the future…. Like the Buddha in one of his former lives—as told in a story of Jataka—who gave himself to a hungry lion which was about to devour her own cubs, the monk believes he is practicing the doctrine of highest compassion by sacrificing himself in order to call the attention of, and to seek help from, the people of the world.”

Most self-immolators' acts of self-sacrifice are premised on a faith in humanity and life rather than a longing for oblivion or abandonment of hope. They believe in humanity and the possibility that a dormant conscience can be stirred, can be enlivened. As Hanh wrote,

“To burn oneself by fire is to prove that what one is saying is of the utmost importance. There is nothing more painful than burning oneself. To say something while experiencing this kind of pain is to say it with the utmost of courage, frankness, determination and sincerity.”

The choice of fire and self-destruction as a means to communicate is admittedly an act of desperation. Depending on the cause and circumstances, such an act may reveal as much about the health of our democracy as the character of the self-immolator. How many protests and poems were ignored, letters, phone calls, and petitions dismissed, international laws violated, fundamental ethical principles transgressed before the conscientious citizen felt compelled to give their life to try and chisel through the hardened heart of a callous and unresponsive power structure?

Anyone paying close attention to the slow motion devastation befalling the people of Gaza cannot help but to feel maddening impotence as reports and imagery stream forth of children forced to carry dead loved ones, people resorting to picking wild plants including weeds to feed their families, small children with bullets to the head, families eating birdseed and other animal feed to stave off starvation, infants and small children dying of hunger and dehydration, and missile strikes killing entire families.

Dr. Jeffrey Nall delivers enlivening presentations and dynamic workshops on the topics featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can send inquiries through Facebook or Substack. He can also be found on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and TikTok.

A single story captures the mixture of horror and helplessness many of us feel. On January 29, 2024, Hind Rajab, due to turn 6 in May, found herself trapped in a black Kia with the dead bodies of her aunt, uncle, and three cousins including a 15-year-old named Layan. Hind’s family was obeying an Israeli order to leave Gaza City for the south when their car was fired upon by the Israeli military. After the initial attack, the 15-year-old, Layan, still alive, called her uncle who put her on the line with the Red Crescent Society emergency services. In a panic, Layan said the children were being fired upon in the car and an Israeli tank was next to them. On the recording of Layan’s call, we hear firing and screams, then the call goes silent. The teenager had been killed.

Left alone and desperate, the 5-year-old Hind called emergency services begging to be saved. “I'm so scared, please come,” she cries out. “Please call someone to come and take me.” And come they did: the Red Crescent Society sent Yousef Zeino and Ahmed al-Madhoun to rescue the child. The paramedics whereabouts were communicated to the Israeli military to ensure their safety and the two men courageously drove to the gruesome scene of violence to save Hind who waited in the shadow of a tank and the company of corpses—her loved ones.

It would take two weeks to discover the result of this daring mission since the Red Crescent Society lost contact with Zeino and al-Madhoun. A preliminary investigation by the Euro-Med Human Rights Monitor determined that Hind and her would-be rescuers were all killed by artillery shelling. Fragments of an American-made M830A1 HEAT shell were found inside of the destroyed ambulance.

After learning of her daughter’s fate, Hind’s mother, Wissam Hamadah, decried the leaders of Israel and the U.S. “For every person who heard my voice and my daughter's pleading voice, yet did not rescue her,” said Hamadah, “I will question them before God on the Day of Judgement. Netanyahu, Biden, and all those who collaborated against us, against Gaza and its people, I pray against them from the depths of my heart.”

There is no question Bushnell knew the story of Hind Rajab. It was a story that reverberated around the world, breaking the heart of every humane person who heard it. Bushnell likely heard Hind’s diminutive voice and Layan’s screams. He probably also heard the words of Hind’s mother, an angry plea for the world to make sense, for a small child not to be left alone with the stench of death only to be killed in broad daylight, by a tank in an age of supposed moral progress. Truly grasping the inhumanity of a death like Hind’s positions us to meaningfully contemplate Bushnell’s choice to self-immolate and understand why his act of self-sacrifice was not suicide.

Self-Sacrifice is Not Suicide

Those who equate suicide and self-sacrifice as exemplified in self-immolation fail to look beyond the surface similarities and grasp the distinct essences motivating the two acts. In a word, they fail to grasp a truth accessible only through reason’s deeper, more comprehensive gaze.

A simple thought experiment helps us grasp the distinction. Imagine that a parent witnesses a person firing a gun in the direction of their child. With only a split second to decide, the parent jumps in front of the child, absorbing the lethal bullets. Would we see the parent as suicidal? Would we act to prevent the parent from acting on their willful agency to honor one of their highest values?

We grasp this vital distinction once more through the Jataka tale that Hanh referenced in his letter to King. In “The Story of the Hungry Tigress,” contained in the Jātakamālā or Garland of Birth Stories, we read that a starving tiger mother has just birthed cubs but is so starved she is prepared to eat her young as they move to drink from her teats. The Buddha, in one of his prior lives, witnesses this unfolding tragedy, and decides to throw himself to the tiger. In doing so, he satiates the mother’s hunger, rescuing her from starvation and the violation of her own young, and saves the unsuspecting cubs. “Thus did the Bodhisattva, who was to be the Buddha long ages afterward, show in this birth, his compassion for all creatures, by sacrificing his body to the wants of a hungry tigress.”

A superficial analysis of the kind featured by mainstream commentators on Bushnell’s death would have us pair the self-sacrificing parent, the incarnation of the Buddha who threw himself to the tigress, and Thich Quang Duc with someone who had succumbed to the worst of despair and acted to end their life because they found life unbearable and desired death. But the parent in this situation does not jump in front of their child to die just as Aaron Bushnell and Thich Quang Duc did not self-immolate for purposes of death. On the contrary, each including our imagined parent was motivated by a reverence for life. As Bushnell’s heartbroken friend, Levi Pierpont, told Democracy Now, his friend “didn’t have thoughts of suicide. He had thoughts of justice. That’s what this was about. It wasn’t about his life. It was about using his life to send a message.”

Those who equate self-immolation and suicide are guilty of the fallacies of either equivocation or false equivalency. False equivalency occurs when we equate two of something that are distinct in important ways. In this case, taking one’s life for purposes of no longer being alive, and taking one’s life to honor one’s deepest values and commitments. The equivocation fallacy comes into play when we engage in a kind of word play that entails exploiting ambiguity or double meaning in a word to try and convince someone of our point. We see this fallacy in action in the deployment of the word suicide to describe the importantly distinct experiences just mentioned. If we are going to call these two different kinds of deaths by the same name—”suicide”—we will be need to recognize their differences to foster reasonable reflection and be careful not to conflate.

Wood committed the equivocation fallacy in his The Atlantic article by arguing that our objection to “violence”—implicitly referring to violence done to others against their will and at the expense of the non-consenting innocent victim—requires us to oppose all other forms of violence including self-immolation. The argument fails in the basic sense that it absurdly implies we must object to violence enacted in self-defense. More to the point, it exploits linguistic ambiguity to try and furtively compel us to arrive at Wood’s preferred conclusion: the denunciation of Bushnell’s self-sacrifice. But a rational analysis requires awareness that we are dealing with two species of violence: violence done by one autonomous being at the expense of another with the aim of advancing egoistic objectives, and another kind of violence done by one autonomous being at their own expense with the aim of honoring universal human rights. We should always be wary of those who hinge their argument on words rather than the deeper experiences that the words are meant to help us think about and discuss.

To clarify, no sensitive person will disagree that seeing a human being burn to death is horrifying. Bushnell’s immolation repulses the viewer. We do no want to see flesh aflame, we do not want to hear cries of the dying. We are sickened. Our skin crawls. Conscious thought is overpowered by visceral feeling. These facts are not in dispute. To the contrary, they are the very basis of the choice.

Bushnell chose this extreme course of action precisely because he felt that his suffering would be not only seen but even felt in a way Palestinian suffering was not. His self-immolation could not be ignored, he rightly surmised, the way Palestinians was ignored: their dismemberment, starvation, sickness, amputations without pain reliever, babies dying in incubators, children shelled in passenger cars, loved ones hanging from limbs after airstrikes, to hundreds gunned down while attempting to secure food. It is no great leap to surmise that Bushnell envisioned his self-immolation as a step toward atonement for the injustices of his society, for the American made shell that killed two brave paramedics trying to save a frightened 5-year-old child.

As he walked to the Israeli embassy, Bushnell said that he was about to “engage in an extreme act of protest,” but then pointed out the suffering he was about to choose for himself was but a small portion allotted to the tens of thousands of Palestinians in Gaza. “This is what our ruling class has decided will be normal.”

Honoring Aaron Bushnell’s Sacrifice

Like the Vietnamese Buddhist monks protesting their persecution under the U.S.-backed dictatorial regime, Bushnell's self-immolation was guided by forethought. He wrote out his final wishes, making plans for his cat and allocation of his last resources. He proceeded with clarity and purpose as he posted a final message to social media, donned his military uniform, and calmly articulated his message and aims before setting himself ablaze before the Israeli embassy in Washington, D.C.

Self-immolation is an extreme, lethal act. No one who loves life comfortably advocates or even endorses such a method to promote peace and human dignity. Such an act is viscerally repulsive to lovers of life. “I don’t want anybody else to die this way,” explained Bushnell’s friend Pierpont, an U.S. Air Force conscientious objector.

“If he had asked me about this, I would have begged him not to. I would have done anything I could to stop him. But obviously we can’t get him back. And we have to honor the message that he left. I would have told him that this wasn’t necessary to get the message out. I would have told him that there were other ways.”

Yet lovers of life like Hanh, Pierpont, and Bushnell are also committed to truth. And this commitment requires admission of even painful truths. Truths like the fact self-sacrifice has the power to stir the lulled conscience of those who inwardly wish to cry out against inane suffering and senseless destruction of innocent life. Thus Pierpont added,

“But seeing the way that the media responds now, now that this has happened, it’s hard not to feel like he was right, that this was exactly what was necessary to get people’s attention about the genocide that’s happening in Palestine. And so, I just—I want people to remember his message.”

If you enjoyed this post please like it by clicking the heart icon. We also invite you to share this post and to leave a comment telling us what you think on the topic and/or what you found important in this piece.

Invite Dr. Nall to Speak

Dr. Jeffrey Nall delivers enlivening presentations and dynamic workshops on the topics featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can send inquiries through Facebook or Substack:

I have said much on the subject of the Gaza War. Like all sane people, I have been horrified by it immediately after I saw Israel ready and prepared to conduct a war of destruction and vengeance in response to the October 7th attack by Hamas. I was horrified when they used the biblical reference of Amalek. This did not bode well for a proportionate response.

Well, almost five months later, It is far worse than my darkest imaginings; it is made worse by U.S. complicity; it is made worse by the silence of so many Jews around the world, including in Israel, though there are some voices. I am one, a Jew of conscience, but I personally know no one here who agrees with me. It is lonely, but my conscience is not seared.

So how could this be? Books, esp. great literary and moral philosophical works have kept me grounded and not fall prey to the voices of tribalism and nationalism. I have been truly fortunate to have read the works of a survivor of Auschwitz, a chemist and a brilliant writer: Primo Levi. He said, when asked about Auschwitz:

"Monsters exist, but they are too few in number to be truly dangerous. More dangerous are the common men, the functionaries ready to believe and to act without asking questions."

So, yes, ordinary people particiapting in the destruction of Gaza. What does "Never Again" really mean?

I truly wish the act did bring more attention and cause change.