"Worthless Degrees" and the Hidden Hand of Values

How Values Shape the Facts of Our Lives

Over the last decade, comedians, sitcoms, and politicians have taken turns criticizing the worthiness of the humanities and broader liberal arts as areas of study in higher education. In the “Thanksgiving” episode (1998) of That 70s Show, Red Forman asks his daughter, Laurie, for an update on her college experience. She replies, “I’ve decided to major in philosophy.” Her brother, Eric, seizes the opportunity to make a dig at his sister, retorting, “That’s good, because they just opened up that big philosophy factory in Green Bay.” The exchange has since been memorialized through a popular online meme.

The irony of criticisms like this one, and those below, is that they unwittingly prove the vital necessity of the humanities and liberal arts for democratic society and individual flourishing. The humanities emphasize the thinking skills and cultural knowledge that enable us to critically assess the claims and beliefs touted as culturally “common sensical.” Here I want to highlight how they help us recognize the hidden hand of value judgments shaping social norms and our individual beliefs and choices.

The Undisclosed Values of Humanities’ Critics

In 2017, then South Dakota Governor Dennis Daugaard recommended students in his state choose “realistic” courses of study and avoid philosophy.

“I don’t think we need to direct kids where they should go, obviously we want kids to follow their dreams, but they can’t be too dreamy…. So they should follow their dreams with their eyes open so that if you’re going to take a philosophy degree at the end of the day the job opportunities for philosophy majors are relatively few and probably don’t pay very well.”

That same year, then Kentucky Governor Matt Bevin urged colleges to steer students toward away from majors with he claimed had poor job prospects.

“If you’re studying interpretive dance, God bless you, but there’s not a lot of jobs right now in America looking for people with that as a skill set.”

Bevin also urged colleges to eliminate entire programs and degrees such as those pertaining to French literature.

“Find entire parts of your campus…that don’t need to be there. Either physically, as programs, degrees that you’re offering, buildings that… shouldn’t be there because you’re maintaining something that’s not an asset of any value, that’s not helping to produce that 21st century educated workforce.”

The joke from That 70’s Show along with Daugaard and Bevin’s arguments indicate the importance of the humanities because the humanities aid us in understanding the influence value-based claims have in shaping our thinking. Not only do all of these criticisms assert, without support, that those with these majors face poor job prospects; they also take it as self-evidently true that any field of study that does not generate skills directly translated to maximum economic productivity are not valuable.

Critics are entitled to make such an argument, but they simply assume what is in question. Rather than offering support for their value-based judgments, Bevin and Daugaard present their conclusions, that these are unworthy fields of study, as a “matter-of-fact” rather than a “matter-of-value.” Their audience is expected to accept, without reasoned support, their value-based assumptions as obviously true. Those who do not question such a claim are more likely to accept the conclusion and its implications. The humanities aid in the development of our autonomy or self-determination by uniquely facilitating the critical evaluation and discussion of precisely these kinds of presumptions about what is most important or valuable.

How Values Shape the Facts of Our Lives

The study of human values is one of the unique domains of the humanities. With a fuller appreciation of the influence values exert over our factual lives we are better equipped to appreciate the important role the humanities play in human understanding.

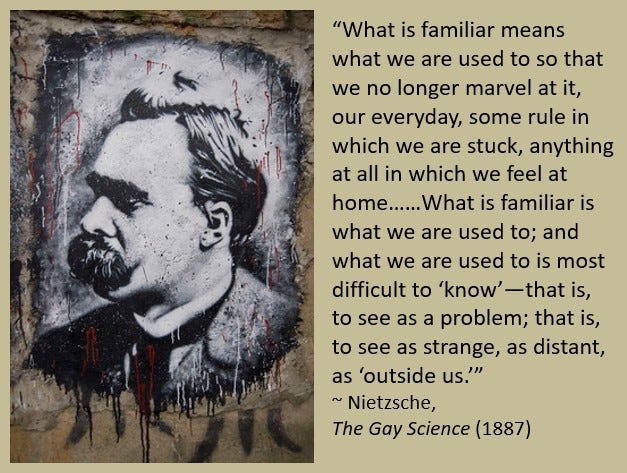

We’re all familiar with the words, “value” and “values.” But that familiarity does not necessarily translate into conscious understanding. A range of philosophers, psychologists, and spiritual teachers have taught us the strange insight that the most familiar to us is often the least understood. As Nietzsche puts it in The Gay Science (1887):

That which is unfamiliar stands out to us as unique or strange. This response generates, at a minimum, some awareness about the thing or belief in question. By contrast, the more familiar something is to us, the less likely we are to critically examine it. Such examination would require a degree of epistemological skepticism that exceeds prescriptions of normal life and dominant culture.

With this in mind let’s think about the meaning of “value.” In one sense, a value is a belief about what matters or is important to us. We sometimes value or deem important material objects like money, a car, a home, or even a favorite cup. We also value certain beings, such as pets, colleagues, friends, and family members. And we value experiences, such as listening to good music, drinking a good cup of coffee, or sharing in good company. To say we value such things, beings, or experiences is to say that they fulfill a desire or purpose of ours. Thus, to value something is to deem it significant, meaningful, desirable or even necessary.

Factual claims are different. They pertain to whether or not something is or isn’t. Our factual claims are rooted in sensory perception: what something looks like, tastes like, smells like, feels like, or sounds like. Even our sensory perception relies upon foundational concepts that transcend human experience in order to cogently organize and therefore make real sense of causation. David Hume made as much clear in explaining the “problem of induction.” (See footnote for more.) Claims that something is “good” or “important” ultimately rely upon values which transcend strictly empirical evaluation. If this thought seems strange just consider the question of whether or not Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. lived a good life.

Did Rev. Dr. King Live a Good Life?

Rev. King received countless credible threats against his life and was finally assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee one day after marching with striking sanitation workers. King died before he turned 40-years-old. He was among the most disliked men in public at the time, never achieved great wealth, and also failed to achieve his goal of uniting the working poor across ethnic boundaries to institute measures such as a basic income, universal guarantee of employment, and reallocating a large portion of the military budget toward social programs to expand the welfare safety net. (Critics of the humanities and liberal arts may also find it noteworthy that King “wasted” his education on degrees in Sociology and Divinity before completing a doctorate in Theology.) Of course, we could mention his success in leading the civil rights movement, winning the Nobel Peace Prize, and becoming one of the most familiar public figures in the United States.

But none of these facts dictate whether or not he lived a good or bad life. Such a value judgment can only be made when we couple the empirically relevant facts of his life with a value-based premise such as, “anyone who lives a life of service to others lives a good life” or “a good life is one committed to advancing social justice.” If we viewed King’s life through the lens of such principles, we would quickly conclude that he lived a good life.

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. lived a life of service to others. [Factual claim]

Anyone who lives a life of service to others lives a good life. [Value statement]

Therefore, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. lived a good life.

By contrast, we would conclude he was a clear failure if we applied the value-principle that “only those who live long lives, were materially prosperous, or were popularly approved of by their contemporaries.”

Previously I gave examples of experiences we value such as drinking a good cup of coffee. The word “good” is a value-laden term that goes beyond mere factual observation. The question of what constitutes a “good” cup of coffee pertains to taste, and taste falls squarely in the axiological territory of aesthetics. The matter of taste is further complicated when we factor in the way our understanding of a thing or experience impacts how we experience it. If we are sufficiently empathetic beings, we might, for example, find our experience of a particular food changed after learning that it is produced by forced laborers, child labor, or perhaps animal cruelty.

To be clear, nothing so far said dismisses the importance of factual information. To exemplify our values, we must understand what is factually true or false, or at least likely true compared to unlikely. Scientific knowledge is essential in grounding humanistic reflection. Our value judgments must be factually informed. But it must also be understood that facts are silent, indifferent, or simply directionless without values.

The Inescapable Influence of Values

The meaning or significance of most facts is determined under the light of our values. Our values dictate the overarching aims that motivate our practical choices and thinking, including how to respond or make sense of empirical truths. These overarching aims are those parts of existence we seek out for their own sake.

Values function as fundamental frames of reference guiding our judgments. They animate otherwise lifeless factual claims about the world. As philosopher Alison Jaggar pointed out, in “Love and Emotion in Feminist Epistemology,” social values are implicitly at work in even the most basic of scientific tasks such as identifying which problems that deserve to be solved.

In Man for Himself: An Inquiry into the Psychology of Ethics (1947), Erich Fromm made much the same point in dispelling the notion that objectivity entails detachment.

“The idea that lack of interest is a condition for recognizing the truth is fallacious. There hardly has been any significant discovery or insight which has not been prompted by an interest of the thinker. In fact, without interests, thinking becomes sterile and pointless. What matters is not whether or not there is an interest, but what kind of interest there is and what its relation to the truth will be.”

Our interests are expressions of our values, be they conscious or unconscious. That we choose to focus our attention on one or another matter logically implies a commitment and, therefore, affirmation of that undertakings value. By recognizing the role values play in our lives we enhance our capacity for objective thought. Subjective, biased thought is more likely to follow self-deceptive thinking that presumes we engage the world as divinities in a state of utter emotional detachment.

The Dangers of Facts without Moral Direction

What’s more, when we fail to tether our lives to foundational values we put ourselves at risk of becoming functionary agents of potentially reprehensible belief systems. Humanist psychologist, Abraham Maslow, warned of the diminished awareness of the centrality of values in human life in his book, Religions, Values, and Peak-Experiences (1964). He wrote:

As Australian philosopher Val Plumwood argued, in Environmental Culture: The Ecological Crisis of Reason (2002), demands for “value-free” thinking tend to favor those in positions in power since their views and assertions are taken for granted as inescapable matters of fact.

“The politics of the emotionally-neutral anthropologist who does not care whether the indigenous people he or she studies are harmed or not through their knowledge-gathering illustrates this clearly, as does the politics of the natural scientist whose work opens the way for destructive exploitation of what is studied. Power is what rushes into the vacuum of disengagement; the fully ‘impartial’ knower can easily be one whose skills are for sale to the highest bidder, who will bend their administrative, research and pedagogical energies to wherever the power, prestige, and funding is. Disengagement then carries a politics, although it is a paradoxical politics in which an appearance of neutrality conceals capitulation to power.”

Values assign meaning—good or bad, worthy or worthless, significant or insignificant—to the objects, entities, and undertakings in life. When we lose sight of the primacy of values, our actions become unprincipled and purposeless. Renowned Russian novelist, Leo Tolstoy, author of War and Peace (1869) and Anna Karenina (1878), illustrates this point by highlighting our tendency to exalt technical progress without a fuller appreciation of the ultimate ends it is intended to advance.

“The medieval theology, or the Roman corruption of morals, poisoned only their own people, a small part of mankind; today, electricity, railways and telegraphs spoil the whole world…. Everyone suffers in the same way, is forced to the same extent to change his way of life. All are under the necessity of betraying what is most important for their lives, the understanding of life itself, religion. Machines—to produce what? The telegraph—to dispatch what? Books, papers—to spread what kind of news? Railways—to go to whom and to what place? Millions of people herded together and subject to a supreme power—to accomplish what? Hospitals, physicians, dispensaries in order to prolong life—for what? How easily do individuals as well as whole nations take their own so-called civilization as the true civilization: finishing one’s studies, keeping one’s nails clean, using the tailor’s and the barber’s services, traveling abroad, and the most civilized man is complete…. Enough individuals therefore, as well as nations, can be interested in civilization but not in true enlightenment. The former is easy and meets with approval; the latter requires rigorous efforts and therefore, from the great majority, always meets with nothing but contempt and hatred, for it exposes the lie of civilization.”

Tolstoy’s use of “religion,” here, communicates a more general idea that transcends religious doctrine and speaks to all of us. By religion he means the contemplation of matters of ultimate concern; the area of humanistic thought concerning itself with “the understanding of life itself.”

Tolstoy’s point is that we are often so busy with secondary pursuits—telegraphs and books to communicate, railways to travel, and hospitals to stay alive—that we lose sight of the ultimate commitments and pursuits that give those activities their true worth. He challenges us to stay concentrated on what we care the most for. To stay aware of the values—be they love, friendship, truth, beauty, aliveness—our communication, travel, and fleeting lives aim to fulfill. If we lack a clear sense of what we are ultimately devoted to, we may busy ourselves with aimless industry that, at best, leads to no-where or, at worst, comes at the expense of life. For Tolstoy, technological progress that fails to advance fundamental human values is mere absurdity.

The larger point here is that human values continue to shape thought, feeling, and action in the world. When we recognize the power values possess, we understand the indispensable role of the humanities in human understanding. The humanities facilitate the creative and critical exploration of competing visions of values including beauty, justice, God, love, truth, and the good life.

The greater our awareness of these contrasting perspectives, the more likely we are to recognize and scrutinize the value-based beliefs presented to us as inescapable matters-of-fact. And such awareness is vital to human autonomy given that value-based presumptions function to shape our education, careers, personal lives, and wider social institutions.

Subscribe

Subscribers will receive periodic posts pertaining to the broad domain of humanistic inquiry, from the insights of great thinkers throughout human history, the meaning and importance of critical thinking and ethics, the underappreciated poetry in everyday existence, to contemporary cultural analysis and the ongoing struggle to combat human oppression and violence. You will also have the opportunity to engage the author and our online community in dialogue about each post.

Why get a paid subscription?

Paid subscriptions directly support Dr. Jeffrey Nall’s efforts to produce and share publicly accessible independent scholarship and analysis. Supporting donations can also be made through PayPal. For more about my work go to JeffreyNall.com and find me on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.

Footnotes

The Problem of Induction

Empiricism and inductive reasoning—conclusions supported by evidence indicating what is likely to be true—rely upon making general claims, based on accumulated evidence, that cannot be confirmed through empirical observation. Inductive claims entail observing particular events or objects and then making claims about their relationship to a more general set of objects or events. We observe, for example, that each of the 1,000 people who did X experienced common result Y. We then conclude that others who are like the observed 1,000 would likely experience Y if they also did X. Such conclusions rely upon the principle of the uniformity of nature, which presumes that all observed regularities or “laws” in the natural world will continue to hold in the future. Yet such a claim could only be confirmed by observation coupled with the very principle it seeks to confirm. As philosopher Nils Rauhut writes:

“Alas, in order to know that that principle is true, we need to assume that a specific inductive inference works. We thus have come full circle; in order to show that inductive arguments are reliable, we had to appeal to the principle of the uniformity of nature and in order to justify the principle of the uniformity of nature we had to presuppose that inductive arguments are reliable. We thus have…begged the question; we ended up presupposing what we tried to establish.”