Death by Poverty: The Lie of Scarcity and the Risk of Spiritual Decline

The common rebuke to the demand of expanding economic rights, as FDR and MLK insisted we do, is that our nation doesn't have the money. Contemporary Poor People’s Campaign organizer, Bishop William J. Barber II addressed this claim in the lead up to the June 18, 2022 Poor People's March on Washington.

“Whenever we start conversations with the lie about scarcity, whenever there's an attempt to address poverty and always the issue is 'how much does it cost,' but when there's a discussion about funding the military or about tax cuts for the wealthy that never comes up. The spirit of Herod and injustice and greed still lives.”

Barber went on to point out that Nobel Peace Prize winning economist Joseph Stiglitz warns failing to combat economic inequality is more expensive than funding proactive policy measures that remedy the problem. And as Barber points out, elected officials who claim we don't have enough money fail to acknowledge the contradictions in their policy decisions.

Limitless Military Spending

In 2020, the United States spent $778 billion dollars on military spending. That is more than triple what China spent, and greater than the spending of China and the next 10 countries with the highest military budget. Military spending comprises more than 46 percent of all federal discretionary spending, that part of the budget that Congress decides how to spend, annually. Another 6 percent is spent on Veterans' benefits. By contrast, just under 10 percent or $159 billion of discretionary spending is spent on education.

According to the National Alliance to End Homelessness, more than 580,000 people experienced homelessness in January 2020. This figure includes 171,000 people in families, 37,000 veterans, 34,000 unaccompanied youth, and 110,000 chronically homeless individuals. Giving each homeless person $15,000 a year for housing would cost less than $9 billion for the year. Giving them $200,000 to purchase an apartment or home would cost less than $117 billion dollars.

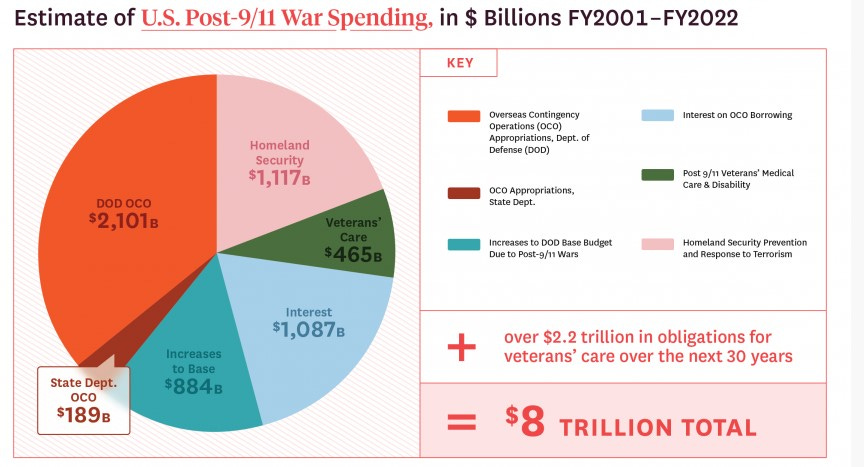

If those figures seem big, consider the U.S. has “spent and obligated $8 trillion dollars on the post-9/11 wars in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, and elsewhere,” between 2001 and 2022.

Nearly 4,000 people died in the state of Florida, in 2005, from inadequate healthcare for years and the Florida legislature continues to refuse to expand Medicaid for all low income residents.

The “war on terrorism” was purportedly declared to prevent another horrific September 11, in which terrorists murdered 2,977 civilians in 2001. But if the aim was to protect human life, we are entitled to ask why legislators did not and do not respond with the same urgency to address thousands of annual deaths due to inadequate healthcare.

Nearly 4,000 people died in the state of Florida, in 2005, from inadequate healthcare for years and the Florida legislature continues to refuse to expand Medicaid for all low-income residents. A 2009 study reported that about 45,000 people die, nation wide, from a lack of resources to address their health care needs.

More recently, a 2022 study determined that 26.4-percent of Covid-19 deaths in the United States would likely have been prevented if our nation provided universal healthcare as do other major industrialized nations. Researchers contend that more than 338,000 Covid-19 deaths were attributable to inadequate healthcare resources for those who were either uninsured or under-insured. (The study authors contend that the U.S. healthcare system is not only inefficient it is also excessively costly. Their recommendation is a single-payer healthcare system to improve care and reduce costs.)

Is it ethical and rational to protect people from terrorism, but leave them to inanely die from hunger, a lack of healthcare, or general lack of vital social supports?

Though such recognition is absent from wider popular media discourse, researchers consistently find what our basic reasoning indicates: that poverty is lethal. One study determined that about 4.5-percent of annual U.S. deaths—hundreds of thousands—are attributable to poverty.

Dominant culture in the U.S. recognizes the moral right of being protected from political terrorism and violent assault. Our military spending is ostensibly aimed at defense. The ethical question then becomes, is it ethical and rational to protect people from terrorism and violent assault, but leave them to inanely die from hunger, a lack of healthcare, or general lack of vital social supports? On what moral grounds can freedom from violent assault be prioritized over freedom from death due to inadequate healthcare or poverty more generally?

Military Spending and Spiritual Decline?

In just a few months, our government has overcome partisan polarization long enough to give Ukraine $31.3 billion in weapons, military and security assistance, and deployed U.S. military and intelligence personnel. For contrast, Russia’s entire military budget is $66 billion dollars a year.

None of us can doubt the need of aid among the Ukrainians as they suffer a Russian war of aggression—one that reminds us of the destructive invasion of Iraq, in 2003, launched by U.S. President George Bush. (In classic “W” fashion, Bush accidentally acknowledged the criminality and brutality of his actions during a speech condemning Russian aggression: “...the result [of anti-democratic repression] is an absence of checks and balances in Russia and the decision of one man to launch a holly unjustified and brutal invasion of Iraq. [Brief pause.] I mean of Ukraine.”)

Logical and ethical consistency demands that we ask, how is it that our national leaders can find billions to fund Ukraine’s resistance but cannot find the money to fund 8 years of paid leave at a cost of $26 billion a year. Why hasn’t this money been allocated to help the forlorn men and women living homeless in our cities? Those we drive by and avert our eyes from out of shame and a feeling of helplessness? The claim that we “don't have the money” is belied by our rapid check cutting for Ukraine and annual military spending. It is what Bishop Barber and others describe as the “lie of scarcity,” a lie they believe perpetuates and protects the status quo.

Here we might well to consider Rev. King’s chastisement, in his April 4, 1967 speech, “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence,” when he declared:

If this moral claim is true, what are the logical implications for our nation? Are we spiraling toward spiritual death?

We must further join the great ethical thinkers of the past in critically assessing the motivations behind military spending and endeavors. Is the real aim to save lives and promote democracy? If so, why do we miss so many pieces of low-hanging fruit? Why not, for example, stop supporting monarchs (Saudi Arabia, Bahrain) or stop subverting democratic governments?

Just imagine how many lives could have been saved had such enormous economic power been marshalled to help save the estimated 5.6 million people dying globally each year from lack of access to healthcare in poor countries. The official civilian death toll in Ukraine today is a tragic 3,381, and officials believe the actual number is many times higher. But are we aware of the fact that 5,700 people are dying every day from hunger—more than 2.1 million people each year?

Bishop Barber also points out that the U.S. is unique in its failure to provide adequate healthcare for its people. Indeed, research has shown that the U.S. health system is last in terms of "affordability, administrative efficiency, equity, and health care outcomes," when compared to peer nations.

If our spending is directed by respect for the dignity of human life, why is the credit card always available for war but slyly put away when we get around to talking about food, housing, and healthcare?

Revolution of Values: Loving People More than Things

The contemporary Poor People’s Campaign is centered on honoring love and human dignity in society, a recognition that objects are not worth more than human beings. This moral distinction is as elementary as it is ignored, and it is one that Rev. King placed at the center of his life and social justice work. As a student of the humanities, Rev. King understood that political projects are hollow without an ethical foundation. There was a reason King was not willing to embrace the “by any means necessary” maxim. For King, some principles were so important that they were worth not only losing but also dying for.

Like other great humanists, Rev. King sought to make clear the distinction between the means and ends of life. This often overlooked or misunderstood distinction was at the center of his activism and philosophy. Some things in life are mere stepping-stones to what we truly value. There are somethings that we value because they help us get something else. Financial gain, wealth, privilege, and material possessions were not, for King, ends. They were mere means. Means to honoring the ends: humanity—dignity, love, justice, joy.

Then there are the sacred ends of life, that which is intrinsically valuable, important for its own sake. Rev. King affirmed that human beings were not means but ends unto themselves. That’s what the German philosopher Immanuel Kant meant when he wrote, “man is not a thing.”

Rev. King quoted theologian, Abraham Mitrie Rihbany, to explain the folly of our nation’s absurd preoccupation with the material means of life. Speaking from the perspective of an imagined representative of “Eastern” thought offering a critique of Western mechanical-technical progress, Rihbany writes:

“You call your thousand material devices 'labor-saving machinery,' yet you are forever 'busy.' With multiplying of your machinery you grow increasingly fatigued, anxious, nervous, dissatisfied. Whatever you have you, want more; and wherever you are, you want to go somewhere else. You have a machine to dig the raw material out of the ground for you, a machine to manufacture that raw material into various articles for you, a machine to transport the articles, a machine to sweep and dust, one to carry messages, one to write, one to talk, one to sing, one to play at the theater, one to vote, one to sew, another to keep things cold, another to keep things hot, another to beat the egg, and a hundred others to do a hundred other things for you, and still you are the most nervously busy man in the world. You have very little, if any, time for spiritual culture.…Your devices are neither time-saving nor soul-saving machinery. They are so many sharp spurs which urge you on to invent more machinery and to do more business.’”

The machines and mechanisms of life originally intended to serve the goals of humanity and living well, explains Rihbany, have become impediments to those very goals. Not because technology is bad, but because we have confused means and ends, tools and their ultimate purpose.

King believed the solution to this confusion was not to turn away from scientific-technological progress, but to return the machinery of human existence to its secondary status as vehicles for honoring human dignity and facilitating flourishing.

“…when scientific power outruns moral power, we end up with guided missiles and misguided men. When we foolishly maximize the minimum and minimize the maximum we sign the warrant for our own day of doom. It is this moral lag in our thing-oriented society that blinds us to the human reality around us and encourages us in the greed and exploitation which creates the sector of poverty in the midst of wealth.”

King’s recognition of the intrinsic worth of humanity—our capacity for expression, feeling, creativity, knowledge, empathy, growth, and self-determination—is what led him to affirm love as what he called the “highest good.” In “A Christmas Sermon on Peace,” delivered Christmas Eve, 1967, explained that agapic love of humanity is

“the key that unlocks the door which leads to ultimate reality. This Hindu-Moslem-Christian-Jewish-Buddhist belief about ultimate reality is beautifully summed up in the First Epistle of Saint John: ‘Let us love one another: for love is of God: and every one that loveth is born of God, and knoweth God. He that loveth not knoweth not God; for God is love….If we love one another, God dwelleth in us, and his love is perfected in us.’”

Rev. Dr. King wished to do more than “reform” the existing social order in the United States. He believed our nation required a fundamental change. “True compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar,” he said, in his Beyond Vietnam speech. “It comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring.” Basic moral decency called for the nation to “rapidly begin the shift from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society,” and to recognize the error of prioritizing profits and property rights over human beings.

Perhaps the problem is that many in positions of social authority lack the very moral imagination necessary for advancing the cause of justice.

This is the cause that the contemporary Poor People’s Campaign has taken up. There is no question that it is a heavy burden with countless obstacles. But as Bishop Barber has pointed out, the history of social change—from abolition of slavery, overcoming segregation, women’s suffrage and more—all began against equally insurmountable odds, with those in power and privilege insisting that such change was unimaginable. Perhaps the problem is that many in positions of social authority lack the very moral imagination necessary for advancing the cause of justice.

If you found this post interesting, please share it with others and like it by clicking the heart icon. And be sure to subscribe if you haven’t already.

Invite Dr. Nall to Speak

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook or by leaving a comment.

Subscribe

Subscribers will receive periodic posts pertaining to the broad domain of humanistic inquiry, from the insights of great thinkers throughout human history, the meaning and importance of critical thinking and ethics, the underappreciated poetry in everyday existence, to contemporary cultural analysis and the ongoing struggle to combat human oppression and violence. You will also have the opportunity to engage the author and our online community in dialogue about each post.

Why get a paid subscription?

Paid subscriptions directly support Dr. Jeffrey Nall’s efforts to produce and share publicly accessible independent scholarship and analysis. Supporting donations can also be made through PayPal. For more about my work go to JeffreyNall.com and find me on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.