At the start of the Spring 2022 semester I began my “Introduction to Ethics” course with the uncontroversial observation that people have often treated others pretty terribly. Consider the fact that children as young as 7 years-old were routinely put to work in factories for 12-hour days during the dawn of industrialism.

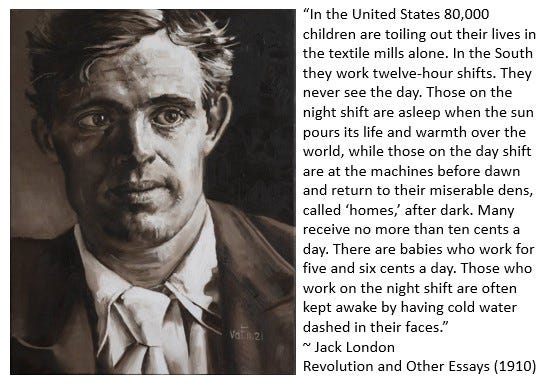

Journalist and acclaimed author of The Call of the Wild, Jack London, described U.S. child labor in his 1910 book, Revolution and Other Essays. He wrote:

“In the United States 80,000 children are toiling out their lives in the textile mills alone. In the South they work twelve-hour shifts. They never see the day. Those on the night shift are asleep when the sun pours its life and warmth over the world, while those on the day shift are at the machines before dawn and return to their miserable dens, called ‘homes,’ after dark. Many receive no more than ten cents a day. There are babies who work for five and six cents a day. Those who work on the night shift are often kept awake by having cold water dashed in their faces.”

London went on to explain that some children as young as six-years-old had already gained eleven months of experience working “the night shift.” And children who are too sick to work were coerced out of bed by hired hands of their employers.

“When they become sick, and are unable to rise from their beds to go to work, there are men employed to go on horseback from house to house, and cajole and bully them into arising and going to work. Ten per cent of them contract active consumption. All are puny wrecks, distorted, stunted, mind and body.”

We might also mention the denial of women the right to vote in the United States, until 1920. This is, coincidentally, the same year that “wife beating” became illegal in all U.S. states. To this we could add that fact marital rape was not criminalized in the United States until the second half of the 20th century.

From Indignation to Ethical Introspection

Pondering the willingness of others to enslave, torture, brutalize, or simply exploit others in ways that are, today, understood as clearly wrong tends to generate disgust and indignation. We ask questions like, “How could people could treat other people so badly?” This leads us into historical, cultural, sociological, and psychological analysis of people’s past behaviors. (Even when the aim is to do ethical analysis, people will often slide into social-scientific analysis, side-stepping the important questions and solutions suggested by moral philosophy.) The presumption is that the evil of these behaviors is quite obvious.

To be clear, I think we ought to be disgusted at the thought of the denigration of human dignity. Our feelings, including feelings of disgust, after all, are partly due to our beliefs, which function as an interpretive lens guiding our understanding of the world. But it’s precisely this appreciation for human dignity that generates concern when our feelings of indignation create a distorted divide between us, in the present, and others, in the (immoral) past.

When I teach ethics I attempt to flip this scripted interrogation to facilitate introspection and moral humility. I exchange the question of why others behaved so badly with the question of how we came to be opposed to racism, sexism, child exploitation, and the like. One inclination is to say that it’s just not in our 21st century nature to accept such abuses. But the fact that so many who came before behaved this way, did so with cultural support; and that we are the same species and have not biologically evolved in the last few centuries, suggests the need for a fuller reply.

I ask students to ponder the source of their morally superior beliefs. I am not asking why the belief in women’s rights, for example, is morally superior to the sexist position. I take it for granted that those of us who are anti-racist, anti-sexist, anti-homophobic, and anti-child exploitation hold positions that are morally superior to the racist, sexist, homophobic, and exploitative positions. These are my questions:

How did we, today, obtain this superior moral wisdom?

Are our beliefs the result, by and large, of our own intellectual effort?

To what extent is our moral goodness as much an accident of social-cultural circumstance as moral badness was?

Are we making adequate effort, on an ongoing basis, to critically evaluate our moral beliefs and choices?

Standing on the Shoulders of Moral Giants

This line of questioning tends to facilitate the basic insight that most of us have done comparatively little work and, therefore, deserve rather little credit for the superior moral beliefs we hold. By and large, we stand on the shoulders of moral giants who daringly confronted the dominant beliefs of the ages and refused to abide by the doctrines and practices endorsed by popular opinion, tradition, and cultural authority. These ethical innovators courageously consulted their own conscience and endeavored to think independently.

This awareness ought to concern us. It implies that many who reject mistaken moral beliefs and embrace the superior positions do so on the superficial basis of adhering to dominant social-cultural influence. And this is the same wellspring of the very beliefs we, today, abhor.

Refusing to Leave Moral Goodness to Chance

One of the first, important lessons of moral philosophy is that moral goodness ought not be left up to chance. The error of many who adhered to, and perpetuated immorality and injustice began in their abdication of the responsibility of independent thought. The fact that we are well within the mainstream of moral opinion should offer very little comfort given that the moral views taken for granted, today, as right were once deemed false by the same cultural common sense that presently endorses them. The point, obviously, is not that we are wrong to be anti-racist, anti-sexist, anti-homophobic and so forth. The point is that the cultural dominance or popularity of these views is coincidental to their moral accuracy.

Realizing that we are not so different from those who actively perpetuated or passively permitted moral wrongs of the past enables us to better pursue moral excellence. We become less confident in our moral purity; less comforted with the fact our moral beliefs fit into the dominant cultural consensus.

Looking Up, Taking Moral Initiative

We begin to ask important questions like, which of the commonly accepted beliefs and behaviors of today will be viewed as ignorant and unconscionable in the future? What are the unrecognized immoralities of the current age for which future generations will repugnantly judge us as we do those who accepted and participated in male supremacy, white supremacy, homophobia, exploiting child labor?

The arts continue to be an ally in aiding us to step beyond cultural convention to ponder such questions. The movie, Don’t Look Up (2021), for example, challenges us all to ponder our moral responsibility for climate catastrophe. Will future generations look upon us, today, as lacking moral sensitivity and aliveness, as we see those who numbly went about their lives as children toiled in factories, people were enslaved, and husbands “disciplined” wives? Educated people are denied the alibi of “ignorance” about the devastation that is now and will be wrought from climate change.

Perhaps future generations will target their moral revulsion at other elements of our ordinary life. Is it outrageous to imagine a future where people will scornfully wonder how we could go about our ordinary lives while homeless people lived in our very midst?

Are the moral ramparts that defend our diets against questions about animal suffering and rights built of hollow rationalizations or will they stand the test of time?

Might people one day view with shock our acceptance of the absence of democracy and co-ownership in most workplaces? Might they condemn the ordinary exploitation of adult labor for the profit of many who do not work? These are, of course, open questions.

Such questions deserve to be considered for their own sake. But they also challenge us to recognize that being good is too often left up to the whims of cultural authority and popular opinion; too much left up to chance.

The solution is to embrace the commandment of ethics to critically evaluate our moral beliefs and lives. Truly differentiating ourselves from those who believed and perpetuated immoral ideologies means opening our lives and thinking to our own critical analysis and honest, good faith dialogue with others. And while we may not always like what we see, we will at least have the opportunity to develop moral integrity.

As someone who grew up anti-racist and anti-homophobic, upon reflection, I have no idea where those beliefs came from--they were just part of who I was/am. I would love to say they are the result of thought provoking conversations in my youth; however, I know that to be untrue. As an adult, I have spent many years studying the systems and institutions of oppression. And, although my beliefs mesh with many in society, I recognize that I stand on the shoulders of the men and women who came before and whose work has enhanced my knowledge a million fold. It is not enough to simply be "anti" anything. I think it is incumbent upon us to learn about the institutions that reify the oppression we see today. In order to truly work towards equality, we must do the hard work of learning--really learning. Reading the work of those who came before and critically evaluating our own thought processes and beliefs and whether or not we believe what we do because it is popular or because we understand and are mindful of the history of the that oppression.