What Would a Suffragist Do? Lessons for Social Change from Our Feminist Foremothers

Commemorating the 103rd Anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment

On August 18, 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment, was ratified, removing a chief obstacle to women’s right to vote. The Amendment stated:

“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

Though the amendment did not remove every barrier for all women to vote, it was nonetheless a major advancement in women’s rights in the United States. One of the chief champions of the Nineteenth Amendment, Susan B. Anthony, died more than a decade before is passage, 40-years after first being introduced to Congress.

We are indebted to our feminist foremothers for advancing women’s rights and for combating the oppression of women in our society. As we commemorate another anniversary of the Nineteenth Amendment, we should do more than praise their achievements. While acknowledging their faults and imperfections including the ethnocentric and classist bias of white suffragists, we should strive to emulate the best of their example and learn from their insights into patriarchal culture and the nature of social change itself.

No Retirement from the Cause of Justice

Our feminist foremothers teach us that the cause of justice belongs to all of us regardless of age. The 1920 voting right’s victory began, in part, seventy-one years before the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. On July 18 and 19, 1848 Elizabeth Cady Stanton and female Quakers hosted the Seneca Falls Convention in New York, the first large public meeting advocating for women’s rights. Abolitionist Lucretia Mott was inspired to organize the convention after being obstructed from full participation in the 1840 Anti-Slavery Convention in London because she was a woman.

Three years later Stanton met Susan B. Anthony. The two went on to become lifelong friends and allies in the fight for women’s equality. In 1872 Anthony and thirteen other women succeeded in casting their ballots in Rochester, New York. They did so in violation of the law. Anthony was later arrested and put on trial. As Susan Shaw and Janet Lee wrote:

“She appeared before every Congress from 1869 to 1906 to ask for passage of a suffrage amendment. Even in her senior years, Anthony remained active in the cause of suffrage, presiding over the National American Women Suffrage Association…from 1892 to 1900.”

Anthony labored for women’s rights for five decades but died fourteen years before women won the right to vote in the United States. Her life and work stand as powerful rebukes to the contention that social change activism is the work of the young. Anthony fought for women’s rights into her eighties. Her example teaches us that there is no retirement from paying the debt we all owe the often unnamed whose labor produced the expanded rights that enable us to live more dignified lives, today.

Yet the best reason to strive to combat oppression and honor human dignity is not to pay an ethical debt. Instead, the change agents of the past show us that such labors of love and principle give us purpose and facilitate the activation of our fuller human potential—our brightest humanity. In responding to the wrongs they sought to rectify, our feminist foremothers were not only subjected to the abuses of power and uncritical popular opinion, they were also rewarded with a joyful fulfilment that the self-serving and status-quo observing rarely experience.

They also provoke us to think of causes of justice within a larger context of human history, progress, and meaning. We are called to look beyond strictly short-term strategic calculations and to ask existential questions. In addition to asking, will this legislation pass or how many politicians currently support it, we are invited to ask, Is this treatment of the “other” ethically defensible? What rules should govern a just society? What would a person of moral integrity do to while others are denied dignity? Anthony, Sojourner Truth, and other feminist foremothers remind us that social transformation is not achieved simply through political calculus; it also requires ethical daring, creativity, and conviction.

Failure is No Excuse for Giving Up

Susan B. Anthony wasn’t alone in laboring for a posthumous victory. Many champions of women’s rights died long before the gains in voting rights, access to contraception, property rights, and educational opportunities were achieved. Their efforts instruct us to pursue just causes out of commitment to ethical principle rather than political expediency. They also exemplify the power of human agency to defy fatalistic decrees that “nothing can be done.”

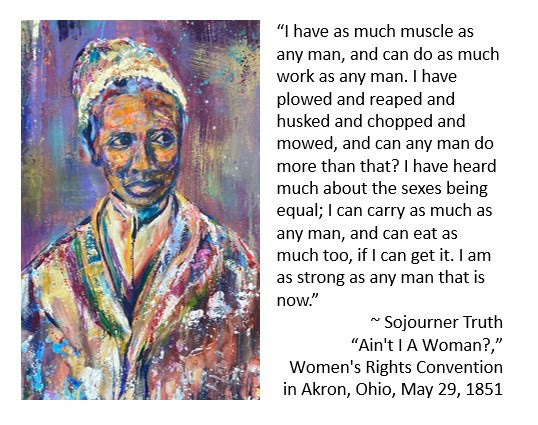

Like Anthony, the abolitionist and itinerant preacher, Sojourner Truth, failed to see passage of the Nineteenth Amendment. Truth delivered her stirring speech, best known as “Ain't I A Woman?,” at the Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio, just three years after the Seneca Falls Convention. She drew on her own experience as an enslaved working woman to explode patriarchal myths of “femininity.” In the earliest transcription of her speech we read:

“I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man. I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that? I have heard much about the sexes being equal; I can carry as much as any man, and can eat as much too, if I can get it. I am as strong as any man that is now.”

Truth highlighted her bodily experiences with food and work to lay claim to her womanhood and puncture the culturally dominant stereotype of femininity. She also challenged the unfairness of depriving women of the full development of their unique capabilities, whatever they might be.

“As for intellect, all I can say is, if women have a pint and man a quart - why can’t she have her little pint full? You need not be afraid to give us our rights for fear we will take too much, for we can’t take more than our pint’ll hold.”

Truth died in 1883, decades before the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified. The same was true of Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, who died in 1911, eight years before her efforts on behalf of women came to fruition.

Born to free black parents in 1825, Harper was another feminist foremother who lent her intellectual capabilities to the causes of abolition and suffrage. In 1858, Harper, a poet, writer, and active Unitarian, refused to give up her seat or ride in the “colored” section of a segregated trolley car in Philadelphia. She did so nearly one hundred years before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat to a white bus passenger in Montgomery Alabama, in 1955.

In 1866, Harper joined Anthony and Stanton to speak at the Eleventh National Women’s Rights Convention in New York City. Harper shared her keen awareness of the wrongs and outrages inflicted upon her due to her racial identity. The compounded difficulty became clear to her when, around 1864, her husband died and she was left widowed with four children and limited resources and opportunities.

During that same speech, in 1866, Harper challenged her white female counterparts to recognize black women’s unique plight as they faced the dual and integrated oppressions of sexism and racism. Harper said,

“You white women speak here of rights. I speak of wrongs. I, as a colored woman, have had in this country an education which has made me feel as if I were in the situation of Ishmael, my hand against every man, and every man’s hand against me. Let me go to-morrow morning and take my seat in one of your street cars…and the conductor will put up his hand and stop the car rather than let me ride.”

Harper gave the example of Harriet Tubman who, despite her service in the U.S. Army, was subjected to racist abuse. Tubman was twice assaulted by white train conductors, one in New Jersey and another in Auburn. Refusing to go down without a fight, Tubman sustained an injured shoulder and broken ribs, in October 1865, while resisting the Auburn conductor's efforts to throw her into either the smoking car or baggage car. Harper chided her audience for failing to recognize the equal urgency of combating racism as well as sexism.

“We have a woman in our country who has received the name of ‘Moses,’ not by lying about it, but by acting it out-a woman who has gone down into the Egypt of slavery and brought out hundreds of our people into liberty. The last time I saw that woman, her hands were swollen. That woman who had led one of Montgomery’s most successful expeditions, who was brave enough and secretive enough to act as a scout for the American army, had her hands all swollen from a conflict with a brutal conductor, who undertook to eject her from her place. That woman, whose courage and bravery won a recognition from our army and from every black man in the land, is excluded from every thoroughfare of travel.”

In the same speech, Harper went on express an ethical principle that would be resounded for generations of social reformers including Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.:

“We are all bound up together in one great bundle of humanity, and society cannot trample on the weakest and feeblest of its members of its members without receiving the curse in its soul.”

For Harper, the full flowering of human dignity required the acknowledgment and honoring of every member of the human family. Those benefited by undue privilege make a proverbial deal with the devil at the expense of their own full humanity, tarnishing their own dignity.

Harper made clear that she did not think women's enfranchisement would immediately achieve the revolutionary goal of eradicating human oppression.

“I do not believe that white women are dewdops just exhaled from the skies. I think that like men they can be divided into three classes, the good, the bad, and the indifferent.”

Women were not inherently better than men, as Harper understood all too well as a black woman subjected to racism from white women as well as men. Yet she also understood from direct experience the plight of disenfranchised women.

Neither Truth nor Harper tasted the fruits of their labor for suffrage. That many working for women’s social equality never lived to see the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment reminds us that the egoistic demand for immediate results is an obstacle to effecting social change. Our feminist foremothers teach us that repeated failure isn’t certain evidence that one cannot succeed. We’re also reminded that the successes won in one age are often born of the long, tiresome, and seemingly fruitless toil of those in preceding ages.

Our feminist foremothers offer us a lesson that must be learned again and again: when an dehumanizing ideology is culturally normalized, naturalized, or portrayed as divinely ordained, it becomes one of the most important mechanisms of oppression.

The tireless struggles of Stanton, Anthony, Truth, Harper, and others to achieve women’s voting rights reveals the irrationality of “insisting on the past”—the fallacy of judging what is possible in the present and the future by strictly referring to what has been achieved and not achieved in the past. They teach us that progress and justice are dead without faithful and imaginative conviction in our cause, commitments that transcend our individual lives and comingle with universal ethical principles. They also teach us that deferring to supposedly prudent “pragmatists”—those singing defeatist hymns that bow to the status-quo —is a death-sentence to social transformation and the dignity it honors.

Seeing What is Invisible: Social Change Born of Critical Consciousness

We too often overlook the difficult intellectual labor of courageously seeing what has been rendered invisible, and thus perfectly hidden. When our feminist foremothers claimed women were independently entitled to basic rights, they were challenging a 5,000-year-old system of belief and practice that presumed the superiority of males over females.

“I ask no favors for my sex. I surrender not our claim to equality. All I ask of our brethren is that they will take their feet from off our necks” ~ Sarah Grimke, “Letters on the Equality of the Sexes” (1837)

While some believe the idea of “patriarchy” is feminist propaganda, a cursory study of the humanities presents endless evidence of male supremacist thought and practice across cultures. In book II of Genesis, we read that the animals God made for Adam failed as adequate helpers. So God formed Eve from his rib “and brought her to the man.” No matter the intellectual gymnastics the Bible’s meaning is clear: woman does not have her own purpose; her purpose is to assist man in living his life. So as to leave absolutely no confusion about this, after Eve eats of the tree of knowledge, God declares “in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children; and thy desire shall be to thy husband, and he shall rule over thee.”

The influential Greek philosopher, Aristotle began his work, Politics (350 BCE), with a discussion of the smallest unit of society, the family. He quotes the poet Hesiod in writing, “First house and wife and an ox for the plough.” After interjecting, “for the ox is the poor man’s slave,” he defines the family as “the association established by nature for the supply of men’s everyday wants…..” To make matters entirely clear, Aristotle later writes that “The rule of a household is a monarchy, for every house is under one head.” For Aristotle the family was no more for women than Eve for herself. Both were for man.

Our feminist foremothers offer us a lesson that must be learned again and again: when an dehumanizing ideology is culturally normalized, naturalized, or portrayed as divinely ordained, it becomes one of the most important mechanisms of oppression. Culturally normalized beliefs or assumptions are rendered common sensical—so taken for granted that questioning them becomes as absurd as questioning the necessity of eating or breathing. Questioning let alone directly challenging such culturally dominant or institutionalized ways of living is scorned as absurdity—foolish and fantastical! This is why our foremothers’ naming and describing of male supremacist culture is an achievement of its own; an achievement of imagination and intellectual courage every bit as important as the political movement that sought to overturn the sexist order of things.

This is the context which allows us to appreciate the boldness and defiance of women such as Mary Wollstonecraft who refused to partner with patriarchy: In her 1792 work, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, Wollstonecraft attributed the misogynistic presumption that women’s predetermined purpose is to serve and advance the interests of men to the Biblical story of Adam and Eve. Given the obvious absurdity “that Eve was, seriously speaking, one of Adam’s ribs,” the deduction that all women were created for men, she wrote,

“must be allowed to fall to the ground; or only be so far admitted as it proves that man, from the remotest antiquity, found it convenient to exert his strength to subjugate his companion, and his invention to show that she ought to have her neck bent under the yoke; because she as well as the brute creation was created to do his pleasure….”

Less than 50 years later, Sarah Grimke wrote, in her 1837 “Letters on the Equality of the Sexes” that it was time for men to stop pointing to Eve’s sin as justification for keeping their feet on women’s necks.

“Woman, I am aware, stands charged to the present day with having brought sin into the world. I shall not repel the charges by any counter assertions, although as was hinted, Adam’s ready acquiescence with his wife’s proposal does not savor much of that superiority in strength of mind that is arrogated by man. Even admitting that Eve was the greater sinner, it seems to me that man might be satisfied with the dominion he has claimed and exercised for nearly six thousand years, and that more true nobility would be manifested by endeavoring to raise the fallen and invigorate the weak, than by keeping women in subjection. I ask no favors for my sex. I surrender not our claim to equality. All I ask of our brethren is that they will take their feet from off our necks.”

To win the freedom women, today, rightly enjoy, they had to imaginatively and perspicuously see through the dehumanizing fog of cultural normality to recognize women’s full humanity. This is what we find in Susan B. Anthony’s 1859 speech denouncing the patriarchal ontology of womanhood.

“The old idea that man was made for himself, and woman for him, that he is the oak, she the vine, he the head, she the heart, he the great conservator of wisdom…she of love—will be reverently laid aside with other long since exploded philosophies of the ignorant past.”

Anthony’s friend, Elizabeth Cady Stanton took the matter further in her 1895 book, Introduction to The Woman’s Bible. Stanton argued that the Bible symbolically and culturally upheld the institutionalization of women’s oppression:

“The canon and civil law; church and state; priests and legislators; all political parties and religious denominations have alike taught that woman was made after man, of man, and for man, an inferior being, subject to man. Creeds, codes, Scriptures and statues, are all based on this idea. The fashions, forms, ceremonies and customs of society, church ordinances and discipline all grow out of this idea.... The Bible teaches that woman brought sin and death into the world, that she precipitated the fall of the race, that she was arraigned before the judgment seat of Heaven, tried, condemned and sentenced. Marriage for her was to be a condition of bondage, maternity a period of suffering and anguish, and in silence and subjection, she was to play the role of a dependent on man’s bounty for all her material wants, and for all the information she might desire on the vital questions of the hour, she was commanded to ask her husband at home.”

Figures like Stanton did not divide politics and culture as though we had to pick one over the other. She recognized that cultural dominance vouched for and maintained political dominance. For women and any unjustly oppressed group of people to overcome their subjection they must unlearn the erroneous and dehumanizing self-image they had internalized.

Through their works of cultural criticism our feminist foremothers teach us that we must not conceive of social change as a narrowly confined, singular activity such as just advocating for changes in politics and the law or just consciousness raising. A holistic approach to social change recognizes the importance of cultural engagement and dialogue—criticism of the ordinary ways of thinking, believing, and living—and actively advocating for changes in social institutions and laws. In sum they teach us the importance of critically interrogating popular opinion, power, and tradition and the necessity of self-examination as well as political strategy and commitment.

If you enjoyed this post please share it with others and like it by clicking the heart icon. Be sure to subscribe if you haven’t already.

Invite Dr. Nall to Speak

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook or by leaving a comment.

Loved reading this reminder of the sacrifices made by our Foremothers, they fought the good fight for us wearing long skirts and corsets, I think we should be grateful that women today can (and should) pick up the banner, in shorts and tank tops if we want.

Frances Ellen Watkins Harper 'the good, the bad and the indifferent' perfectly describes my view on the current state of humanity as a whole, some things never change, I am grateful to these brave women for effecting the changes that they did.

Fantastic post. Really enjoy your perspective. Lots of great insights here and thinking how it relates to your post about Camus and The Plague. Victories have to be re-won even when they are won. For women’s rights we see that I’m the last few years. A right women won in 1973 has to be fought for again like Sisyphus pushing the boulder back up the mountain.