Rev. Dr. Martin Luther, Jr. is one of the most revered figures in American history. Each year we commemorate his birth with a national holiday; a monument in Washington DC features his quotes and effigy; and nearly 90% of Americans view him favorably.

Our nation’s collective memory of Rev. King is perhaps best summed up by the “fun facts” coloring page my son brought home in 2019 when he was in first-grade. A cartoon depiction of King stands in the center of the page holding two flags, one reading “freedom” and the other reading “equality.” Surrounding him are four statements:

“I was a key leader in the American Civil Rights Movement.”

“I believed in, and fought for, equal rights for African Americans.”

“I helped end legal segregation and discrimination in the United States.”

“My famous speech, ‘I Have a Dream,’ promoted freedom and equality for all.”

The Rev. King most of us honor each year fits neatly with the vision of our nation triumphantly overcoming its immoral missteps, making King’s dream—a dream ostensibly woven into American identity—a reality. Our nation’s unjust past becomes further evidence of its greatness since we generated not only the injustice but also the solution to that injustice. It was a test of our greatness and we passed.

But the King we think we know is a self-serving fable of those with economic and political power; one that betrays the full vision of the just society he died struggling to build; a fable that hollows out his most incisive social critiques, dulling his prophetic philosophy of social transformation in the service of love. The result is a harnessed legacy used to maintain the status-quo.

When Rev. King Was Hated

Before being assassinated on April 4, 1968, Rev. King was one of the most hated people in the United States. He was viewed favorably by just 33% of Americans, in August 1966. For contrast, both former President Donald Trump and current president Joe Biden are viewed more favorably and less unfavorably than Rev. King. As of October 2022, about 44% of Americans view President Biden favorably while 41% view former president Trump favorably.

In August 1966, 63% viewed Rev. King unfavorably and 44% viewed him as “highly unfavorable.” And that was before King gave his most controversial and widely condemned “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence” speech. King was disapproved of by a larger portion of the population before his death than Joe Biden and Donald Trump are disapproved of at this time of political polarization.

The King We Do Not Remember

Many inured to white supremacy hated Rev. King because of his well-known efforts to undermine racism. But there were other reasons for his high disapproval rating. As King himself noted, even some members of the civil rights community objected to his expansive concern for wider societal transformation.

Students in my college classes inform me each semester that they are taught that Rev. King was a civil rights leader who advocated for nonviolence to peacefully end southern segregation. They do not learn that Rev. King explicitly recommended “militant” nonviolent tactics to achieve social change and rejected the idea that being “moderate” was necessarily good.

On March 25, 1968, ten days before his assassination, King was asked by Rabbi Everett Gendler to answer whether or not he labeled himself a “moderate” in the struggle against racial injustice. King answered with clarity and precision:

"If by moderation we mean moving on through this tense period of transition with wise restraint, calm reasonableness, yet militant action, then moderation is a great virtue which all leaders should seek to achieve. But if moderation means slowing up in the move for justice and capitulating to the whims and caprices of the guardians of the deadening status quo, then moderation is a tragic vice which all men of goodwill must condemn."

King was undoubtedly motivated by peace and love. The ethic of love—a love that extended to every human being including those most difficult to love, our “enemies”—was the very value inspiring his work. King refused to remain silent about the Vietnam war precisely because he viewed even those deemed enemies of his country as his brothers and sisters.

The kind of peace King sought was one that honored the dignity of all in the society. He differentiated between what he called a “negative peace,” understood as “merely the absence of tension” and a positive peace—a true peace—connoting a condition of justice and brotherhood. In his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” (1963), King wrote:

“I think this is what Jesus meant when he said, ‘I come not to bring peace but a sword.’ Now Jesus didn’t mean he came to start war, to bring a physical sword, and he didn’t mean, I come not to bring positive peace. But I think what Jesus was saying in substance was this, that I come not to bring an old negative peace, which makes for stagnant passivity and deadening complacency, I come to bring something different, and whenever I come, a conflict is precipitated, between the old and the new, whenever I come a struggle takes place between justice and injustice, between the forces of light and the forces of darkness. I come not to bring a negative peace, but a positive peace, which is brotherhood, which is justice, which is the Kingdom of God.”

Though we ostensibly honor the life and work of Rev. Dr. King each Martin Luther King Day, it is clear most lack basic understanding of his overarching social analysis and activist project. Rev. King spent the last years of his life speaking out and organizing against what he viewed as the immorality of capitalistic materialism and American militarism as well as white supremacy.

Economic Injustice

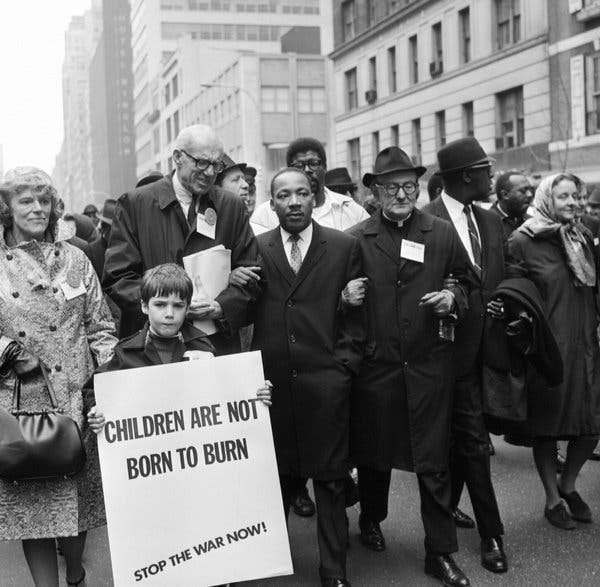

On April 4, 1967, exactly one year before his death, Rev. King delivered his boldest national address titled, “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence.” King called for the United States to withdraw from Vietnam and begin a “radical revolution of values” by channeling the millions of dollars spent on war to address the dire needs of the nation’s poor. King believed that materialism, militarism, and racism formed a giant “triplet of evil,” and that those who love humanity and seek justice must recognize the interconnectivity of all three.

“When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered.”

King came to this conclusion after observing that millions of black people remained in dire conditions even as important advances had been made in civil rights including ending segregation and expanding voting rights. As early as the bus boycott years King had argued that those in power pit poor whites against ethnic minorities to prevent poor people from working collaboratively to change the social order.

In “The Drum Major Instinct” sermon, King described talking to wardens at the Birmingham jail. The officers argued that segregation was beneficial to everyone. When the conversation turned to the pay received by the white officers, King suggested they ought to be marching with the civil rights movement.

“You’re just as poor as Negroes….You are put in the position of supporting your oppressor. Because through prejudice and blindness, you fail to see that the same forces that oppress Negroes in American society oppress poor white people. And all you are living on is the satisfaction of your skin being white.... And you’re so poor you can’t send your children to school. You ought to be out here marching with every one of us every time we have a march.’”

King’s commitment to love enabled him to have empathy for even those contributing to his own oppression. That empathy, in turn, generated insight into the psychological motivations that drove those with relatively little power toward hateful, dehumanizing ideologies.

His awareness of the oppression experienced by poor whites was one reason he believed using violence would be counterproductive to achieve racial equality. Visiting violence on poor whites, themselves subjected to economic injustice, would only entrench the existing racial polarization, which in turn helped maintain economic class divisions. King understood that black people and other minorities disproportionately bore the burden of poverty as they do, today. He also knew that everyone who was poor was oppressed and that this included the millions of poor whites in our nation.

Through his civil rights work Rev. King continually came face to face with the dire conditions of the poor across the United States. These experiences caused him to conclude that racial equality and the broader goal of human rights could not be achieved, in the United States, without a radical campaign against economic injustice. In his 1967 lecture, “Nonviolence and Social Change,” King said,

“In our society it is murder, psychologically, to deprive a man of a job or an income. You are in substance saying to that man that he has no right to exist. You are in a real way depriving him of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, denying in his case the very creed of his society.”

To make good on its promise of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, King believed that the United States needed to ensure its citizens’ basic needs were met. In Where Do We Go From Here (1967), King wrote that the United States could initiate this transition by guaranteeing a livable minimum annual income for every American family as well as ensuring all workers, regardless of industry, are paid a fair wage.

“There is nothing but a lack of social vision to prevent us from paying an adequate wage to every American citizen whether he be a hospital worker, laundry worker, maid or day laborer. There is nothing except shortsightedness to prevent us from guaranteeing an annual minimum—and livable—income for every American family.”

According to Rev. King, we ought not allow ourselves to be “deluded” by the myth of capitalist ideology. In his defiant “Three Evils of Society” speech, delivered August 31, 1967, King cleverly observed that U.S. political policies favor “socialism for the rich and capitalism for the poor.” We use the mechanisms and power of government to help those with the most power and wealth rather than those with the greatest human need and the least power.

The problem, in part, according to King, is that we have adopted a mythical narrative about capitalism.

“We have deluded ourselves into believing the myth that Capitalism grew and prospered out of the protestant ethic of hard work and sacrifice. The fact is that Capitalism was built on the exploitation and suffering of black slaves and continues to thrive on the exploitation of the poor – both black and white, both here and abroad.”

King Believed Capitalism, Not the Poor, was to Blame

Running counter to the culturally exalted model of combating poverty through non-profit, non-governmental philanthropy, Rev. King believed that poverty could only be remedied through political-structural transformation. He challenged us to recognize that poverty is primarily the result of economic exploitation and not individual character defects. “The way to end poverty,” King explained in his “Three Evils” speech, “is to end the exploitation of the poor.” And we should ensure poor people have “a fair share of the government services and the nation’s resources.”

Attempting to solve the problem of poverty by exclusively teaching poor people how to “improve themselves” and better manage their financial resources is a bit like teaching black boys and men to learn how to navigate white supremacy by not wearing hoodies or staying out of the “wrong” neighborhoods; or like trying to help women combat sexist harassment by encouraging them to watch what they wear. Suggestions like these fail to address the root of the problem and simply blame the victim. The suggestion that working poor people simply adopt better money management techniques, go back to college, or seek another job are also distractions from the fundamental economic injustice violating their dignity.

To be clear, I am not arguing Rev. King believed that individuals have no responsibility in their life circumstance. The problem is that we overemphasize individual choices with too little awareness of the much larger structural circumstances that leave ordinary people, most of whom work hard, with little to show for.

Militarism

King is well-known for his commitment to nonviolence in the struggle for racial justice. Few appreciate that King insisted that nations were also morally obligated to renounce the use of violence to achieve their objectives. In his 1967 “Christmas Sermon on Peace,” King argued that nonviolence should also be deployed “in all areas of human conflict” including international affairs.

King saw that militarism dehumanized, maimed, or killed its participants. The invader and the invaded both endure spiritual obliteration. In “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence,” King contended that the “giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism” reinforced one another, preventing the flourishing of a truly just society. He argued that the United States was wrong to take military action in Vietnam and that the death and suffering it was contributing to was immoral.

“This business of burning human beings with napalm, of filling our nation’s homes with orphans and widows, or injecting poisonous drugs of hate into the veins of peoples normally humane, of sending men home from dark and bloody battlefields physically handicapped and psychologically deranged, cannot be reconciled with wisdom, justice and love.”

King’s comments point us to that most painful and instructive of Vietnam War photos: that of the nine-year-old girl, Phan Thi Kim Phuc, fleeing a South Vietnamese napalm bomb attack on her village on June 8, 1972. The children were mistakenly believed to be North Vietnamese soldiers.

King’s “Beyond Vietnam” speech exemplified the rejection of what Erich Fromm had called, in a 1962 address, “social narcissism” or what we might, today, call ethnocentrism: the irrational exaltation of one’s own cultural group—their beliefs, experiences, values, and interests—over others. King noted the constraints we feel when questioning our own leaders in times of conflict.

“Even when pressed by the demands of inner truth, men do not easily assume the task of opposing their government’s policy, especially in time of war. Nor does the human spirit move without great difficulty against all the apathy of conformist thought within one's own bosom and in the surrounding world.”

But King refused to silence his conscience, explaining that the United States had, before the Vietnam war, actively worked against the Vietnamese independence movement, siding with and funding French colonial control.

“Even though they quoted the American Declaration of Independence in their own document of freedom, we refused to recognize them….Our government felt then that the Vietnamese people were not ready for independence, and we again fell victim to the deadly Western arrogance that has poisoned the international atmosphere for so long.”

Our nation then endorsed the authoritarian regime of Ngo Dinh Diem, subjecting Vietnamese peasants to more torment.

“The peasants watched and cringed as Diem ruthlessly rooted out all opposition, supported their extortionist landlords, and refused even to discuss reunification with the North. The peasants watched as all this was presided over by United States' influence and then by increasing numbers of United States troops who came to help quell the insurgency that Diem's methods had aroused.”

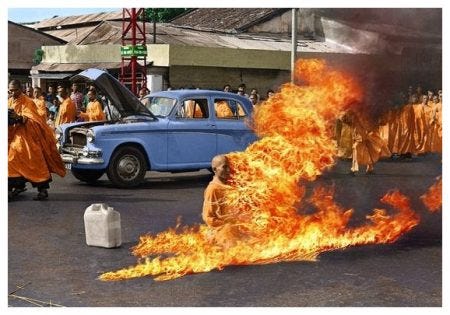

Diem’s repressive regime persecuted Buddhists and jailed thousands of political enemies suspected of being communists in “reeducation” camps. He implemented secret police and routine torture. Buddhist monk Thich Quang Duc self-immolated himself on a busy street in the city formerly known as Saigon, on June 10, 1963 to protest the U.S. backed autocrat.

Critically examining militarism would allow us to recognize the lie that a nation like the United States lacked the economic resources to care for essential human needs and flourishing. If hundreds of millions of dollars could be spent to intervene in a foreign nation’s internal affairs, it could not be reasonably argued that same nation lacked resources to address homelessness, hunger, education, and other vital needs of its people. King insisted that nations that prioritized funding destruction over human flourishing risked spiritual disaster.

“A nation that continues year after year to spend more money military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death.”

Rev. King also warned us not to be deceived by peaceful professions of men enacting the grandest displays of violence. In his December 24, 1967 “Christmas Sermon on Peace,” King highlighted the profound disconnect between the stated motives—words—and actions of the men who led military actions around the world.

“The conquerors of old who came killing in pursuit of peace, Alexander, Julius Caesar, Charlemagne, and Napoleon, were akin in seeking a peaceful world order. If you will read Mein Kampf closely enough, you will discover that Hitler contended that everything he did in Germany was for peace. And the leaders of the world today talk eloquently about peace. Every time we drop our bombs in North Vietnam, President Johnson talks eloquently about peace. What is the problem? They are talking about peace as a distant goal, as an end we seek, but one day we must come to see that peace is not merely a distant goal we seek, but that it is a means by which we arrive at that goal.”

King instructs us to pay attention to men's deeds rather than their professions, and to see that someone’s aims are best understood through observing their actions.

A larger point is that even the well-intentioned are mistaken in separating methods and goals. The means we deploy to achieve our goals often shape the goals themselves. Thus he called on us to recognize that eternal value of moral and spiritual integrity.

In the pursuit of a peaceful society and world we must recognize, King explained in his Christmas sermon, that “ends are not cut off from means, because the means represent the ideal in the making, and the end in process.” The path we take to arrive at our goal affects the goal itself so that we cannot so simply prioritize the end goal and flippantly choose "any means necessary." The two are tied together.

Such thinking was what guided King to conclude that nonviolence was the difficult though practical and ethical choice in combatting systemic racism and white supremacy. In sum, King believed it necessary that we prioritize integrity and consistency with our highest principles, even as we face the greatest of challenges.

King’s emphasis on striving to live a life of integrity may be one of his greatest lessons. King consistently prioritized truth and ethical consistency over flattering those in power and those with whom he shared bonds. In the final speech of his life, “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop,” given the day before his assignation, King offered criticisms of religious authorities who behave in contradictory ways and pursue self-interest. In his “Beyond Vietnam” speech, he chastised those who would question why he would take an interest in his nation’s military bombardment of a foreign nation.

“Could it be that they do not know that the good news was meant for all men—for Communist and capitalist, for their children and ours, for black and for white, for revolutionary and conservative? Have they forgotten that my ministry is in obedience to the one who loved his enemies so fully that he died for them?”

King called for an end to the Vietnam war and criticized the United States for betraying its earlier role as a force for revolutionary freedom. In order to speak with integrity about the wrongness of using violence to resolve conflicts amongst members of the same society he needed to speak

“clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today—my own government.”

King’s comments indirectly refer to the tens of thousands of Vietnamese civilians the U.S. military killed through bombing and massacres like that of Mỹ Lai. Following the speech King was roundly condemned by major news outlets. Had his approval rating been measured at the time it would have most certainly fallen even lower.

Santa Claus-ification of Martin Luther King

Today, King is celebrated and discussed in narrow terms as a peaceful civil rights leader who had a dream of ending racism. Fifty years following King’s assassination, conservative commentator, Sean Hannity, described King as a great speaker and visionary leader. He and a guest panel commemorated King’s efforts to combat racism and segregation. One year later, conservative commentator, Bill O’Reilly, conveyed his admiration for King, describing him as one of the “greatest” men in “American history.” O’Reilly said he admired that King “was so calm. And his message was look, we just what the Constitution says: Equal rights to pursue happiness. Equal rights to pursue the American dream. We want to be treated the way whites are treated.”

Hannity and O’Reilly did not discuss King’s objections to the Vietnam war nor did they observe that King described the U.S., at the time, as the “greatest purveyor of violence in the world.” They did not explore his commitment to militant, disruptive activism toward social transformation. Neither commentator mentioned King’s advocacy of a guaranteed income for all Americans nor his explicit endorsement of expanding the social safety net provided by the government. These men were either uneducated about Rev. Dr. King’s philosophy and activism or they actively presented half-truths for some unstated aim.

To be clear, Hannity and O’Reilly are not alone in offering narrow, superficial praise of a man who was once hated by the same nation that now honors his birthday with a national holiday. More recent conservative commentators have suggested King would have objected to contemporary Black Lives Matter protests on account of the fact some led to property destruction.

Such critics have clearly not listened to King’s “Nonviolence and Social Change” lecture, later published in The Trumpet of Conscience (1968) ,where he calls for widespread civil disobedience “as forceful as an ambulance with its siren on full” to tackle the interrelated emergencies of racism and poverty. King discusses in some detail the violent rioting of his day, affirming his commitment to nonviolent activism, but also insisting on the importance of distinguishing between property and persons.

“A life is sacred. Property is intended to serve life, and no matter how much we surround it with rights and respect, it has no personal being. It is part of the earth man walks on; it is not man.”

Contemporary philosopher, Cornel West, describes the trend of reductively celebrating King’s legacy, ignoring seminal features of his life and work, the “Santa Claus-ification” of Martin Luther King, Jr. West said,

“I don’t want to sanitize Martin Luther King. I don’t want to deodorize Dr. Martin Luther King. I don’t want to disinfect Dr. Martin Luther King, and we’re not gonna domesticate Dr. King.”

The contention is not that we must simply agree with King’s spiritual-moral-political project or all of his recommended solutions to the ails of society. Reasonable people of even shared moral commitments are inevitably going to disagree on some matters. Each of us is not only entitled to but also obligated to scrutinize King’s arguments and analysis. He is, like the rest of us, a fallible mortal. Yet we dishonor his life and work by conveniently exalting pieces of the project he sacrificed his life to accomplish while ignoring the parts that are uncomfortable to consider. King was a perspicuous student of ethics, religion, history and current affairs. He also risked and ultimately lost his life in nonviolent struggle to achieve a more just, loving world. The least we can do is give his ideas a fair-hearing. We might just be better for it.

Please share and like this post by clicking the heart icon.

Invite Dr. Nall to Speak

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook or by leaving a comment.

Subscribe

Subscribers will receive periodic posts pertaining to the broad domain of humanistic inquiry, from the insights of great thinkers throughout human history, the meaning and importance of critical thinking and ethics, the underappreciated poetry in everyday existence, to contemporary cultural analysis and the ongoing struggle to combat human oppression and violence. You will also have the opportunity to engage the author and our online community in dialogue about each post.

Why get a paid subscription?

Paid subscriptions directly support Dr. Jeffrey Nall’s efforts to produce and share publicly accessible independent scholarship and analysis. Supporting donations can also be made through PayPal. For more about my work go to JeffreyNall.com and find me on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram.