In “Woman-made: Finding Beauty and Agency in Childbirth, I explained the importance of Canadian painter, Amanda Greavette’s depictions of childbirth. Her artwork powerfully counters the culturally dominant tendency to diminish if not outright disappear maternal agency.

Popular cultural largely represents childbirth as something that happens to women rather than something women do. Instead of showcasing a range of birth experiences, including empowered women potently producing human life, we are usually shown disempowered women in life-threatening situations; situations that require others to come to women’s rescue. This pervasive depiction of childbirth is inaccurately pessimistic.

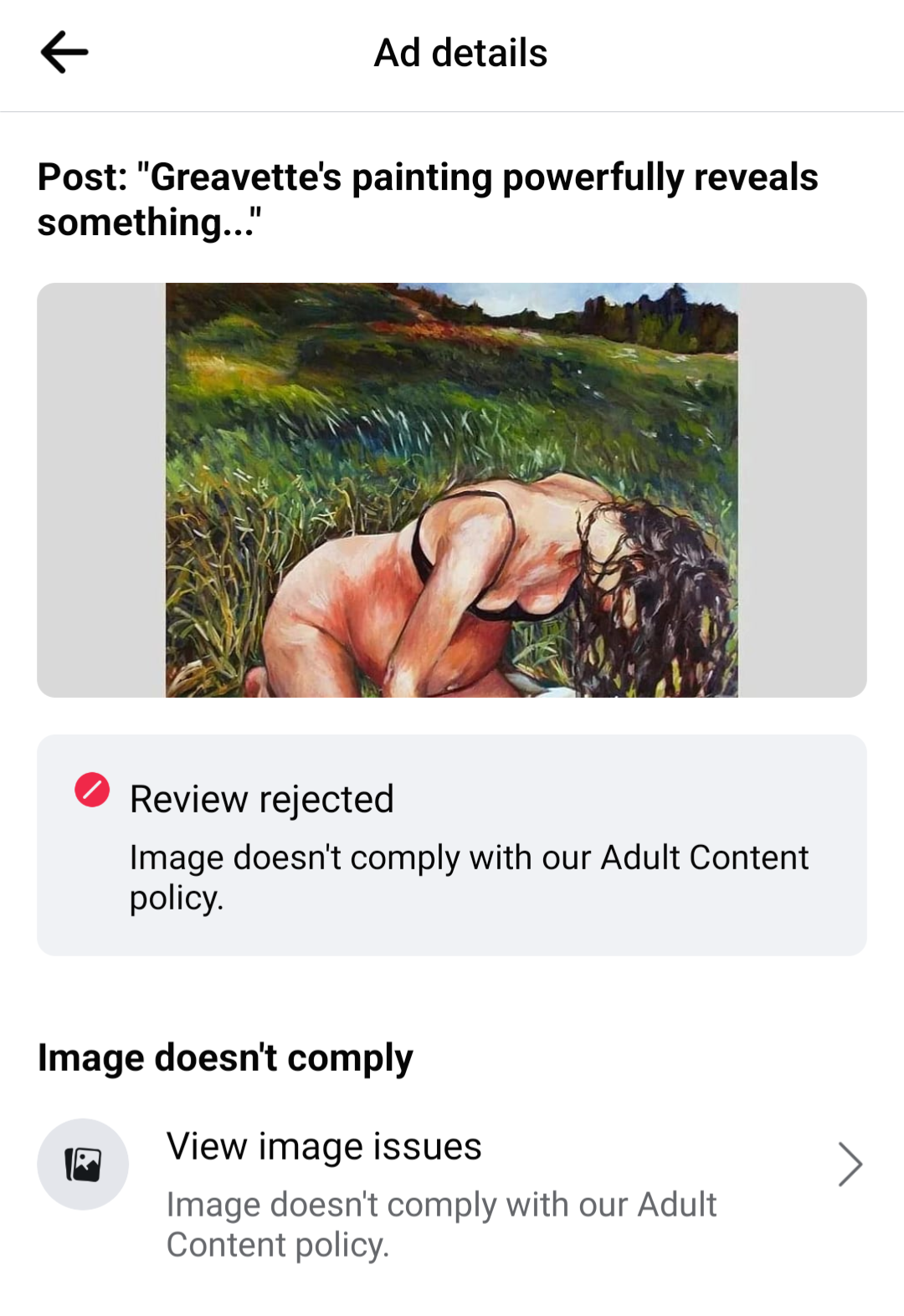

To generate greater exposure for the reflection and Greavette’s art, I placed a Facebook ad promoting a post about the article and featuring an image of the painting in question. Facebook rejected the ad. I then requested a review but the initial rejection was quickly affirmed. This ironically validated the very thesis of the initial post: that our maternal origins and the agency of birth-giving women are marginalized—pushed out of sight—in popular culture.

Childbirth as Adult Content?

Why was the Facebook post rejected? Because it violated Facebook’s “adult content” policy.

The natural question here is, what constitutes “adult content”? The phrase seems to pertain to pornography. The policy states that ads must not contain "nudity, depictions of people in explicit or suggestive positions, or activities that are overly suggestive or sexually provocative."

Apparently, Facebook’s system believes that childbirth is equivalent to pornography.

Apparently, Facebook’s system believes that childbirth is equivalent to pornography. How else to explain the rejection on grounds of the “adult content” criteria? The painting in question shows a woman on her knees over a bed. No one is having sex but we do see her butt along with the life she is birthing. Apparently the mother's bottom or the act of giving birth, itself, was deemed too sexually “explicit” or “suggestive” for wide viewership.

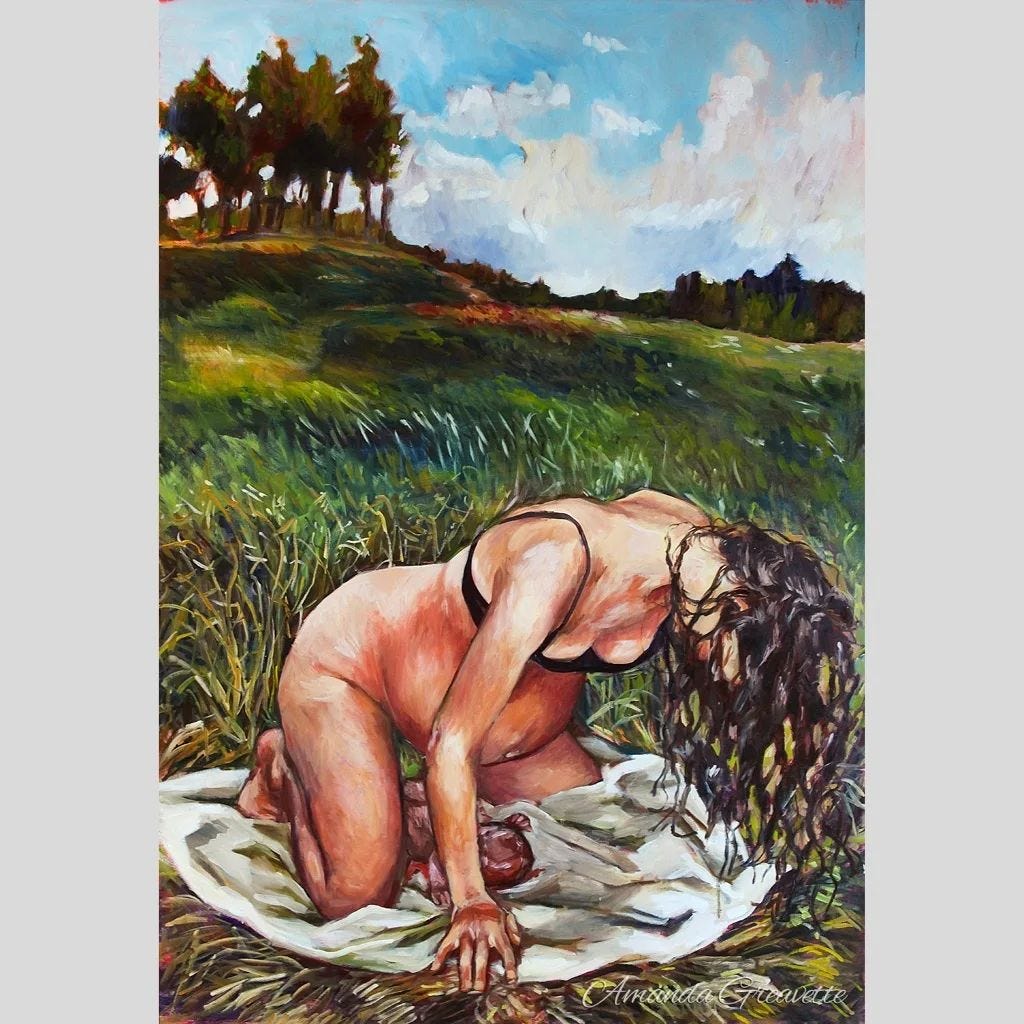

In an attempt to circumnavigate the initial rejection I tried boosting another post featuring a link to the same article but with a different Greavette painting. In this work we see a woman in a meadow on her hands and knees, bearing down and birthing her baby. Her backside is directed away from the viewer’s eye, so we only see her thigh, hip, and the right side of her bottom. We also see her stomach as well as her neck and shoulders.

The results were the same. The initial request and a subsequent review were both “rejected.”

After the second round of rejections I attempted to boost the post with yet another painting. This one featured absolutely no nudity assuming we don’t count faces, necks, and hands. By then the system had grown distrustful of my poor judgment because the ad review process stalled. So I got in touch with a person in the company’s advertisement division.

I spoke to a helpful representative named Sebastian who lives in Columbia. He explained that the first and second reviews of content are conducted exclusively by artificial intelligence. Sebastian acknowledged that AI isn’t as intelligent as the company would like it to be, and that the earlier images ought to have been permitted. The problem is that the system lacks the ability to make important distinctions between sexually connotative nudity and non-sexual nudity. In other words, the AI cannot consistently implement Facebook’s own policies.

Now may be a good time to ask ourselves about over-reliance on unintelligent machines to make important decisions.

Here we are reminded of how far removed we are from the often touted world of truly intelligent machines. Discernment and contextualized understanding continue to be distinctly human competencies. Now may be a good time to ask ourselves about over-reliance on unintelligent machines to make important decisions. We should contemplate how AI is now permitted to make significant decisions about what people will or will not be permitted to see, read, or think about in the social media world. If we truly treated social media platforms like Facebook as the town square they are touted to be, we might insist on more human moderators.

Returning to the issue at hand, the Facebook representative explained that images of nudity are even more likely to be flagged when they are accompanied by facial expressions of pleasure. Thus it could be that the first painting had two strikes against it. Not only did it show the woman’s butt, it also showed smiling birth attendants. If such matters were entirely up to Facebook’s AI, joyful, body-affirming birth would be prohibited while images of somber women covered up by hospital gowns and lying in bed would be just fine.

The inability…to discern between debasing images of exploitive sexualization and images joyfully honoring the body and the source of human existence indicates a dangerous degree of social immaturity.

The inability (for people or the machines we deploy) to discern between debasing images of exploitive sexualization and images joyfully honoring the body and the source of human existence indicates a dangerous degree of social immaturity. How are we to thoughtfully discuss reproductive ethics, at a time when abortion is on the lips of so many in the public, when we are deprived of elementary representations of women's pregnancies and birth experiences?

Where Babies Come From

The problem isn’t entirely to do with AI. Sebastian, the Facebook representative, explained that posts like the one I was trying to promote would also likely face the prospect of being flagged as “inappropriate” by ordinary users. He gave the example of his home country, Columbia, saying many view childbirth and breastfeeding as private affairs and do not readily approve of seeing images of these actions in the public sphere. I shared that this was also true of many in the U.S. To this point, someone responded to my post about Greavette’s painting with the comment, “Why do we need to see that to understand birth?”

To answer this question I’ll pose another, do we really know where babies come from and how they are made? Do we know really who creates and births them? Most would say, of course we do! I’m not so convinced. We may know “where babies come from” in a general and abstract sense, but the broader cultural discourse around childbirth and pregnancy suggests that we lack genuine awareness that women create rather than have babies. Take three commonplace expressions.

“The baby was born on (insert date).”

“When is the baby due?”

“Did she have the baby, yet?”

Just ask yourself how we might respond if someone spoke in comparable terms of an athletic championship:

“The championship was won on (insert date).”

“When will the championship be won?”

“Did the Tampa Bay Buccaneers have the championship, yet?”

Each of these sentences diminishes or omits the agent responsible for the result in question. Championships are not just “won” without someone winning them. Neither are babies simply “born” without mothers birthing them. Similarly, we find the question, “When will the championship be won?,” strange because it leaves out the important detail of who we have in mind to win the championship. The third example sounds disconsonant because the word “have” typically implies passivity. We have breakfast—even if someone else made it—or have our oil changed (usually by someone else). But we don’t have championships. And mothers don’t just have babies.

But we don’t have championships. And mothers don’t just have babies.

We speak of birthing women in childbirth as we would a ball in a football game rather than an athlete acting in the world to affect a particular result. We sometimes attribute more agency to the newborn than to the mother with phrases like the baby “came out” as we describe the manner or time of “the birth.”

Ordinary language attributes more agency to reading a book than to birthing a human being.

Ordinary language attributes more agency to reading a book than to birthing a human being. No one would say, for example, “The Handmaid's Tale, was read on last week” or “When will The Handmaid's Tale be read”? In ordinary communication we would refer to the person who read or intended to read the book in each of these sentences: “Diane read The Handmaid's Tale last week” and “When will Diane read The Handmaid's Tale?” That we attribute more agency to someone reading a book than a woman birthing new life ought to be inspire critical introspection on the matter.

The Power of Art

Clearly, we have a problem. But it is one that transcends Facebook. For all of the patriarchal propaganda promoting reproduction as women’s true purpose, there has been an accompanying effort to symbolically annihilate the fact mothers do more than have babies, they quite literally make them. Works of art and cultural representations that illustrate and dramatize the hidden reality of maternal agency in pregnancy and childbirth give us a clearer picture of the facts of life. These facts enable us to fully appreciate the mothers who made us; and they inspire us to recognize that pregnancy isn’t the carrying of a preformed person, but the process by which a woman, when she decides to remain pregnant, forges a person.

Art and the wider world of popular cultural expression functions to illustrate and dramatize otherwise abstracted truths. Art helps us feel the true—visceral truth.

Art can help us connect to and truly grasp the fundamental truths of human existence. Too often we think that grasping something as a piece of information is sufficient for genuinely knowing—understanding it. But that’s usually not true. Art and the wider world of popular cultural expression functions to illustrate and dramatize otherwise abstracted truths. Art helps us feel the true—visceral truth. This is why artistic representations of childbirth like Greavette’s are so powerful. It's also a reminder of why the humanities are more important than we generally give them credit for being.

If you found this article interesting, please share it with others and like our post by clicking the heart icon. And be sure to subscribe if you haven’t already.

Related Reads

Speaking Services

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook or by leaving a comment.

Very interesting piece again. Funny that I recently read a similar piece about a slightly different aspect of AI and how it can look at things:

https://psyche.co/ideas/when-will-humorous-ais-press-our-buttons-with-their-jokes

As to the question of the abstract idea of birth, I'm not sure I agree with all of it. I think most people simply are focused on what they're focused on and can't think about it in depth. People don't think about birth until they're confronted with it directly when they get pregnant or get someone pregnant. They also don't think about death until they're confronted with it. Doesn't necessarily mean they have a bad idea of what it is. Just that it's not front of mind for most people.