In my book, Feminism and the Mastery of Childbirth, I show birth is almost always represented as a life-threatening emergency in popular culture. Pregnant women are at the same time portrayed as helpless non-agents in need of rescuing; props for someone else's agency. Canadian artist, Amanda Greavette's powerful and inspiring portrayals of birth are revolutionary counterweights to this mainstream distortion of women's birth abilities and experiences.

In this piece, the birthing woman’s facial expression communicates focus and intensity but not affliction. We are given an honest picture of the difficult work women—our mothers—undertake when they birth new life. It is not easy work, but it is also not impossible.

How strange that birthing women should have to accommodate others during her birth work.

Many will be surprised to see the woman birthing her creation on her knees rather than on her back. We are accustomed to seeing women give birth on their backs in the lithotomy position. This common place birth position has long been chosen by the doctor and for the doctor’s convenience. How strange that birthing women should have to accommodate others during her birth work.

The positions of the caregivers are also noteworthy because they symbolize the centrality of the pregnant woman in a humanizing birth setting. One caregiver is kneeling by the bed, another leans in supportively. On the other side, one places a loving hand on her lower back, and the fourth facilitates the birth. Countering dominant medical practice and cultural portrayal, the birthing woman is returned to her proper place at the center of the birth experience.

We should also contemplate the expressions of the woman’s caregivers. Notice the joy and confidence their faces and body language communicate. They do not fan the flame of “birth terror,” looking onward with irrational panic and fear. This is a representation of a safe birth experience; and such experiences constitute the overwhelming majority of births, according to the World Health Organization.

Part of the power of Greavette’s work is that it openly acknowledges and conveys the very real difficulty of women’s birth work. But it also insists on treating this labor with the reverence and dignity it deserves, refusing to accept prominent stereotypes of feminine weakness and infantilization.

Such a representation is a stark contrast with the panic and “rescuism” of Hollywood depictions where the medical staff dictate to the birthing woman and act upon her as one would an object. Part of the power of Greavette’s work is that it openly acknowledges and conveys the very real difficulty of women’s birth work. But it also insists on treating this labor with the reverence and dignity it deserves, refusing to accept prominent stereotypes of feminine weakness and infantilization. Women giving birth deserve all the support they desire, but rarely do they need to be saved.

As creatures of culture, our beliefs and the experiences they shade and shape are powerfully influenced by popular cultural portrayals. Therefore, we cannot underestimate the importance of diversifying the images and stories of childbirth in comedy routines, childbirth guides, movies, TV-shows, and commercials.

What kinds of popular culture representations of childbirth have you seen?

Can you think of a recent movie or show, maybe advertisement or piece of art that represented childbirth? How did it portray birth and how was it different from Greavette's painting? Leave us a comment and let us know.

Revealing Our Hidden Maternal Origins

A powerful aspect of this painting is that it reveals something ubiquitously hidden from us within the dominant culture: our maternal origins. We see the mother sending her creation into the world before our eyes. She is not “having” a baby anymore than we “have” a diploma, workday, or championship. She is doing something, but not just anything. She is birthing new life; she is igniting the spark of being. This is divine work, is it not? How else to describe the generation and animation of a human being?

Greavette's painting reminds us that we did not simply “arrive” here. Our mothers made and birthed us. This is the reality absurdly invisiblized throughout our culture, hidden behind stories of babies delivered by storks, made by God, or simply described as having been born.

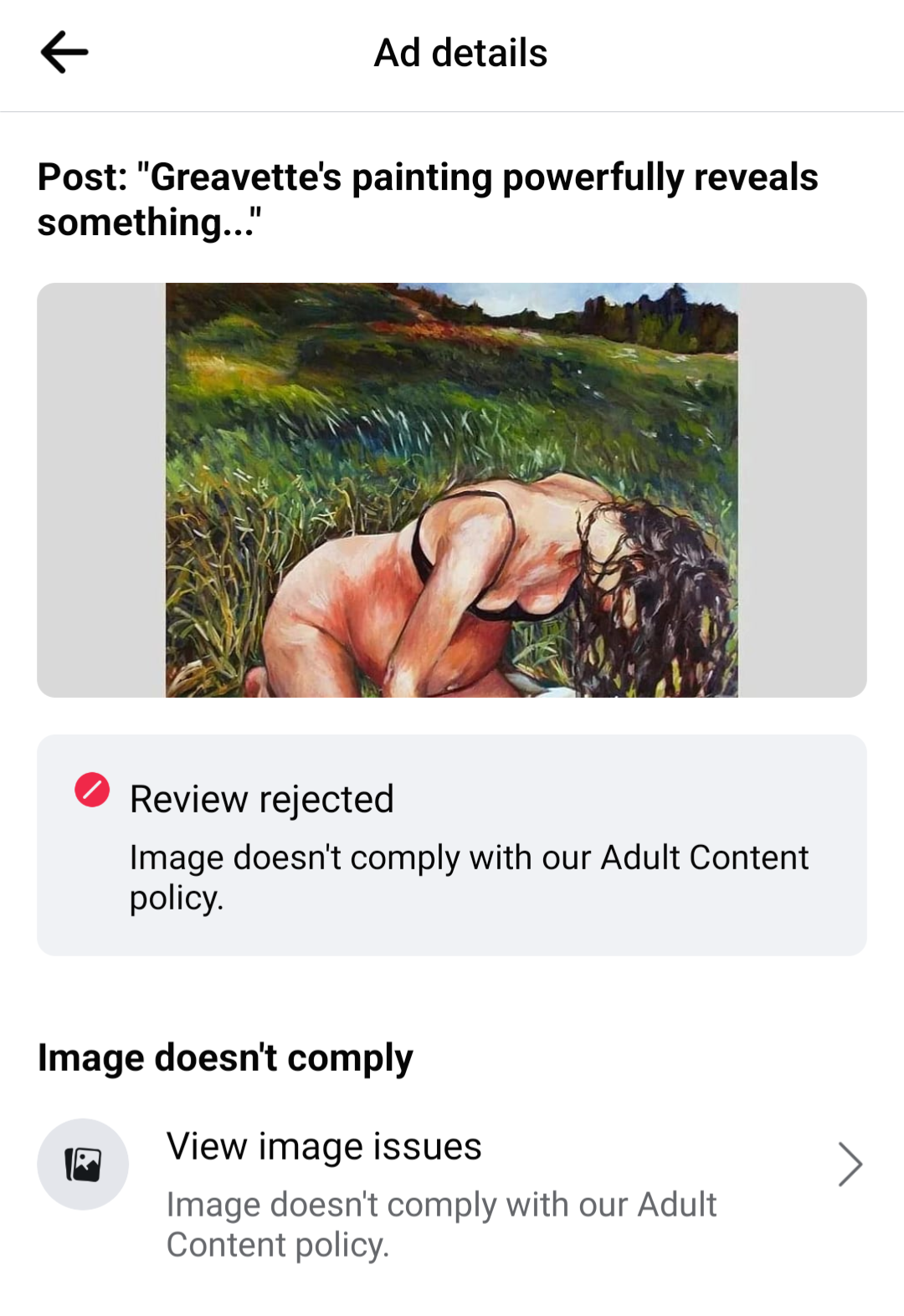

Facebook’s rejection of my attempt to boost a post featuring an image of this painting quintessentially expresses this “backgrounding” our maternal origins. The ad was rejected because it violated the organization's “Adult content” policy.

I then attempted to boost a post featuring a different painting by Greavette that showed less of a birthing woman’s body. The results were the same.

The natural question here is, what constitutes “adult content”? The phrase seems indicative of pornography.

That policy states ads must contain not "nudity, depictions of people in explicit or suggestive positions, or activities that are overly suggestive or sexually provocative." The first painting in question shows a woman on her knees over a bed. No one is having sex but we do see her butt. We are left to conclude that either the mother's bottom was deemed too “explicit” for wide viewership, or the act of giving birth itself was judged to be too “suggestive.” The latter seemed most likely since the second painting shows very little of the woman's unclad body.

The inability to discern between debasing images of exploitive sexualization and images joyfully honoring the body and the source of human existence indicates a dangerous degree of social immaturity. How are we to thoughtfully discuss reproductive ethics, at a time when abortion is on the lips of so many in the public, when we are deprived of elementary representations of women's pregnancies and birth experiences? Do we really know where babies come from and how they are made?

Read the follow-up to this article: “Are Paintings of Birth Pornographic? Facebook’s A.I. Thinks So, and Why That’s a Problem”

The Implications of Birth Agency

Learning to recognize the agency in women's birth projects not only ensures dignified birth experiences, it also helps us grasp the fact that women do not merely have babies, they make them. When we grasp that they make them, we are in a better position to tackle important and often controversial ethical questions around abortion rights. We begin to understand that the question is not whether or not a pregnant woman ought to have to have the baby, but whether or not she ought to be made to make a baby.

My sense is that this vital ontological distinction helps alleviate some of the moral concern that some—men and women—have about abortion. When we properly locate agency in pregnant women, we are in a better position to more generally honor women’s reproductive autonomy in all of its forms, be it honoring their decision about the conditions they prefer to give birth in or honoring their decision about whether or not to end an undesired pregnancy.

If you found this article interesting, please share it with others and like our post by clicking the heart icon. And be sure to subscribe if you haven’t already.

Related Reads

"Are Paintings of Birth Pornographic? Facebook A.I. Thinks So, and Why that's a Problem

Speaking Services

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook or by leaving a comment.

These Are My Hours is a full-length documentary featuring a birth much like Amanda’s pieces of art. It includes no commentary from anyone but the birthing woman and the camera never leaves her side. The mother is not disturbed. The baby is not taken from her. It gives viewers a new perspective on birth. The creators ( 2 midwives) have taught classes to college students on the contrast of this film and birth in popular media via a guest lecture entitled “Birth and the Media”

www.thesearemyhours.com