For the Love of War and the Fear of Death

Fear, Fallacies, and the Failures of Mainstream Journalism and the General Public. Part II in a series exploring the Iraq War 20 years after the "Shock and Awe" invasion

The 2003 Iraq War stands as a crucial lesson in the dangers of uncritical thought and conformity and the vital necessity of critical thinking for democracy. Far too many in the American public fell prey to government leader’s unsubstantiated, alarmist claims about Iraq.

In October 2002, most in the U.S. believed Saddam Hussein was close to having nuclear weapons. Nearly a sixth of the nation believed he already had them. A majority—66% (2002) and 57% (2003)—mistakenly believed that Hussein had a role in the September 11, 2001 terror attacks. This sentiment was expressed by a pro-war demonstrator in Melbourne, Florida, on February 15, 2003, who carried a sign reading, “Remember 9/11 and let the bombs fall.”

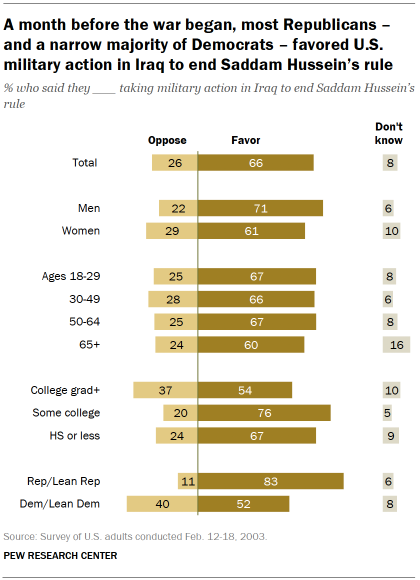

After more than a year of hearing those in power warn of Saddam Hussein’s support for terrorism, weapons of mass destruction, and desire to harm the U.S., 66% of the public favored military action in Iraq one month prior to the invasion.

The public’s obsequious embrace of the Bush administration's talking points was facilitated by the widespread failures of journalists in the mainstream media. Major news outlets frequently echoed and amplified the administration’s WMD claims rather than subjecting them to sustained critical interrogation. As CNN's Howard Kurtz put it, years after the war, “All too often, skepticism was checked at the door, and the shaky claims of top officials and unnamed sources were trumpeted as fact.”

A March 2004 report by the University of Maryland's Center for International and Security Studies concluded that journalists tended to accept “the Bush administration’s formulation of the ‘War on Terror’ as a campaign against WMD, in contrast to coverage during the Clinton era, when many journalists made careful distinctions between acts of terrorism and the acquisition and use of WMD.” Reporters also authored stories that “stenographically” relayed the administration’s claims about WMD rather than scrutinizing or contextualizing them.

Voices critical of the Iraq War were marginalized or entirely silenced. On February 25, 2003, MSNBC terminated popular commentator, Phil Donahue, for giving a platform for critics of the war. An internal memo at the network made the intent of Donahue’s firing clear: “He seems to delight in presenting guests who are anti-war, anti-Bush and skeptical of the administration’s motives.” The network could not allow Donahue’s program to become “a home for the liberal antiwar agenda at the same time that our competitors are waving the flag at every opportunity.”

Read Part I: “Invading Iraq: A Bipartisan Tragedy”

Fairness & Accuracy in Reporting’s study of 393 people appearing on major nightly news programs, from January 30, 2003 to February 12, 2003, found that the vast majority—76%—were current or retired government officials and just 14% questioned the position of the Bush administration on Iraq. Only three of the sources—less than 1%—were identified with groups or organizations with an anti-war position.

Not only did the corporate media privilege pro-war perspectives, it frequently gave voice to the pathological love of death—necrophilia. In The Heart of Man (1964), pioneering social theorist, Erich Fromm wrote that necrophilia entails the exaltation of objects and force over the living and reason.

“The necrophilous person is driven by the desire to transform the organic into the inorganic, to approach life mechanically, as if all living persons were things. All living processes, feelings, and thoughts are transformed into things. Memory, rather than experience; having, rather than being, is what counts. The necrophilous person can relate to an object—a flower or a person—only if he possesses it….”1

The machine-loving necrophiliac, Fromm contended, is more fascinated with “devices which can kill millions of people across a distance of several thousand miles within minutes, than he is frightened of and depressed by the possibility of such mass destruction.”

What better exemplifies necrophilia than fawning over weapons being readied for a military invasion? In the lead up to the 2003 Iraq invasion some journalists excitedly gushed over the beauty and might of military machinery rather than interrogate the dismembering effects of that machinery. Norman Solomon's documentary, War Made Easy (2007), provides multiple clips of journalists using the word “love” to describe their feelings about warfare machinery. NBC news journalist Hanson Hosein said he had “fallen almost in love with the F/A-18 Super Hornet” while Brian Wilson of Fox News said, “I love the [A-10] Wart Hogs.” Others described the technical specifications and capabilities of fighter jets and bombs with giddy enthusiasm.2

There is something else lacking from this extensive discussion and visual representation of missiles, bombs, tanks, and other military hardware: dead bodies.

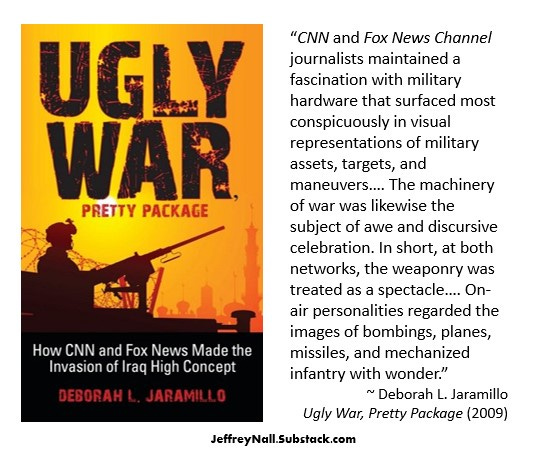

During the Iraq War, cable news networks across the political spectrum cheerfully reported minute details about military equipment the way sports analysts poor over athletic stats. CNN developed what they internally called digital “baseball cards” featuring the image and capabilities of various U.S. military machines like the M1A1 Abrams and the M2A3 Bradley. In Ugly War, Pretty Package (2009), Boston University professor of film and TV studies, Deborah L. Jaramillo wrote,

“CNN and Fox News Channel journalists maintained a fascination with military hardware that surfaced most conspicuously in visual representations of military assets, targets, and maneuvers…. The machinery of war was likewise the subject of awe and discursive celebration. In short, at both networks, the weaponry was treated as a spectacle…. On-air personalities regarded the images of bombings, planes, missiles, and mechanized infantry with wonder.”

News networks’ routine coverage of military weapons featured former or current military figures narrowly discussing the weapons from the standpoint of strategy, technical capabilities, and military efficacy. Ethical matters pertaining to when utilizing such weaponry is acceptable and the likely effects of such weaponry on human life and the environment were not prioritized. “The use of military analysts to explain the weapons is a way of giving us the military's point of view,” explained Jaramillo, “and getting us to think in terms of strategy instead of people.”

There is something else lacking from this extensive discussion and visual representation of missiles, bombs, tanks, and other military hardware: dead bodies. Such coverage made war a bloodless abstraction: a strategic goal carried out by a set of unnamed figures in uniform using “state-of-the-art” weaponry. Ends, biophilia—the love of life—and the guiding values of humanity were supplanted by machines, mechanisms, and the means of life.

The Manipulative Power of Fear and Other Fallacious Appeals

Those who can convince us that we are in danger can also convince us to engage in, or tolerate forms of violence we would otherwise never accept. In The Heart of Man, Fromm argued that much of the violence in the world is motivated by fear. The most common of violence is committed or endorsed when done for the purpose of defending “life, freedom, dignity, property—one’s own or that of others.” Much of the reactive violence we commit in response to fear results from irrational thoughts and manipulation.

Writing amidst the Vietnam War, the wider Cold War, and with acute awareness of the looming dangers of nuclear war, Fromm observed,

“Very often the feeling of being threatened and the resulting reactive violence are not based upon reality, but on the manipulation of man’s mind; political and religious leaders persuade their adherents that they are threatened by an enemy, and thus arouse the subjective response of reactive hostility.”

Fromm added that the fact wars almost always must be portrayed as defensive to be accepted reminds us that most people “cannot be made to kill and to die unless they are first convinced that they are doing so in order to defend their lives and freedom….” Yet it is also true that this intuitive opposition to violence is all too easily overridden by fallacious appeals to power, fear, and popular opinion.

The Iraq War reminds us of the power of fear-based appeals to convince many to support the most extreme forms of violence. Philosophers have long recognized the dangerous and irrational potency fear exerts over thought and action. We commit the fallacious appeal to fear when we use the threat of something bad happening to convince others of our claim. Put differently, appealing to fear means trying to justify our proposition by pointing out the supposed dangers of not accepting the belief in question.

The Bush administration repeatedly deployed this manipulative sleight of hand by answering the question, “why should we invade Iraq” with the answer, “because if we don’t something bad will happen to us.” Condoleezza Rice urged us to support military action to avoid “mushroom clouds” from nuclear weapons. It is difficult to imagine a more explicit appeal to fear.

Fear based appeals use the risk of something bad happening to us as the basis for accepting a claim: We should support the invasion of Iraq, so we aren’t victims of another terror attack. But the fact we would be afraid of Iraq having WMD does not itself prove the nation's leaders have them, nor does it prove the nation would use them on us or that the only way to resolve the problem is to launch a military invasion. Fear, on its own, is not a reliable source of truth, and it cannot take the place of reasoned judgment and factual substantiation of a claim.

Fear-based appeals often attempt to justify a claim by relying on that very claim. That is to say, fear-based appeals are often accompanied by the fallacy of circular argument, also known as begging the question. A circular argument is one in which we try to support a claim with the very idea that is in question! The Bush administration’s argument, roughly, was that we had to invade Iraq to do something about the country’s WMD program. But how do we know that Iraq has WMD? Because that WMD program poses an existential threat to the United States and its global interests.

The careful reader will notice that the reason given above to support Iraq had WMD is a repeat of the claim, an argument that runs in a circle and goes exactly nowhere. It is as if someone argued we should believe in God because of the risk we run of ending up in hell. But if hell is only a reality if God exists, then it makes no sense to trouble ourselves with hell until God’s existence has been established. Similarly, we ought not worry about Iraq creating “mushroom clouds” until sufficient evidence has been established to show Iraq has such weapons. This is particularly true when taking military action will predictably result in the deaths of thousands of innocent civilians, not to mention many thousands of soldiers.

Fear’s insidious influence on our thinking goes beyond our being manipulated by those in power to believe something because we are afraid of it. Many of us are also afraid to question ourselves—our basic beliefs and worldview—and the authorities and institutions we have come to trust, rely upon, and identify with. The renowned 20th century philosopher, Bertrand Russell, argued that human progress and the flourishing of freedom of thought required us to disobey and overcome irrational fear. In Principles of Social Reconstruction (1916), he wrote:

“But if thought is to become the possession of many, not the privilege of the few, we must have done with fear. It is fear that holds men back—fear lest their cherished beliefs should prove delusions, fear lest the institutions by which they live should prove harmful, fear lest they themselves should prove less worthy of respect than they have supposed themselves to be.”

The Iraq War stands as a testament to the costs of the continued failure to renounce fear as the motivating agent of thought and action. Perhaps now is the time to bravely question those institutions we have so long cowered in support of.

The susceptibility of so many otherwise thoughtful, non-violent people to be misled into supporting a war reminds us of the importance of critical, independent thought. A wise public and free press must be able to recognize fallaciousness appeals and insist on factual support and rational argument. In addition to fear-based appeals and circular reasoning, those in power often attempt to justify their claims by exploiting irrational deference to authority. Something is not true simply because those in power say it is. Having social and/or political power does not necessarily enhance the quality of our reasoning abilities, nor does it take the place of a good argument. As philosopher Elliot D. Cohen put it in Critical Thinking Unleashed (2009),

“In an open society, political leaders are not to be idolized and worshipped as gods among humans. Like anyone else, their views can be called into question if they fail to fit the facts as rationally determined. Such a society is antiauthoritarian, realistic, and democratic in its emphasis on enlightened self-governance. In contrast a closed society is authoritarian, and its leaders lead by demanding blind obedience.”

To maintain a free society and our own ethical decency we must confront fear—our own and those fears stoked in us by others—with intellectual and ethical courage. We must respond to political paternalism with independence of thought and a demand for reasoned argument. Thinking critically requires us to disentangle the truth from power and fear. The capacity to make such distinctions may make the difference between war and peace, between life and death.

If you enjoyed this post please share it with others and like it by clicking the heart icon. Be sure to subscribe if you haven’t already.

Invite Dr. Nall to Speak

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook or by leaving a comment.

Fromm references real-life examples of professed lovers of death including Hitler and Stalin. He also discusses General Millan Astray who was confronted, in 1936 by Spanish philosopher Unamuno. General Astray’s favorite motto was “Viva la muerte!” or “Love live death!” Fromm also highlights the Italian fascist, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti's Initial Manifesto of Futurism (1909) in which he explicitly endorses misogyny and celebrates war and militarism. Fromm does not but could have named Theodore Roosevelt, as well, given his explicit endorsements of the powers of warfare to facilitate manly greatness. A more recent example of this “necrophiliac” enthusiasm was on display when MSNBC's Brian William described images of tomahawk missiles being launched from two U.S. naval vessels as "beautiful." The missiles were launched at a Syrian air base by the Trump administration in April 2017. Though Williams was roundly criticized, there was comparably little scrutiny of CNN's unctuous coverage of a Raytheon Company tomahawk missile facility. The report mentions that each missile costs in excess of $1 million but failed to place this figure in the context of the U.S. military budget. Instead all of the focus was on the unique capabilities of the weaponry. Following the Trump administration's dropping a MOAB bomb in Afghanistan, in 2017, Fox News' Geraldo Rivera commented, "Well, one of my favorite things is watching bombs drop on bad guys."

See the unambiguous expressions of love and enthusiasm for weapons of war at the 39:55 minute mark in War Made Easy.

Notice the fawning coverage in the western media of the technology and arms being sent to Ukraine. The same perverse wonder and praise for weapons of war. And Biden who cheered on that Iraq invasion continues to beat the drums of endless, hopeless wars. Sadly the left has completely lost touch with the antiwar movement that spoke loudly in 2002-2003. They have been completely disoriented and turned upside down by Trump.

msDNC deserves to die with its lies. It's all I watched before Oct. 7th. I had no idea what the world thought of America and why. Now I know the truth about Israeli genocide and America's wars and the curtain has fallen. I'll never believe msm or cable again.