Going to the Movies...with the Pentagon

War as Cinematic Abstraction. Part II of a series exploring the intersection of movies and the military

The following is the second post of a series dealing with popular American culture and military service. The first piece is available here: “Giving Veterans More than ‘Thanks.’”

Few of us truly know and understand war. This is one of the reasons our ritualized “thanks” of veterans often ring hollow. Fewer than one in ten Americans are now, or once were in the military. An even smaller share of the population are combat veterans.

In place of direct experience or educated insight, much of our thinking has been shaped by popular culture’s cartoonish characterization of American warfare. Community events, movies, news reporting, and advertisement campaigns centered on honoring veterans rarely give us a big picture view of military service. Businesses pursue profits by symbolically connecting their brand to the U.S. military through marketing campaigns around Memorial Day and Veteran’s Day extolling soldiers’ “heroism” and the greatness of our military.

News programs feature the voices of upper-level officials who rarely offer a window into the treacherous toil of combat. Instead they offer rosy characterizations of mission progress and tout our virtuous objectives. At times officials in the Defense Department have actively misrepresented the facts about the progress and character of U.S. wars, as was clear with the war in Afghanistan.

Popular culture represents our nation's military conflicts as simple matters of good guys going up against the bad guys. That the good guys are our guys is unquestionable common sense. The moral ambiguities of warfare, ill-defined notions of victory, and questionable political decisions motivating military action are all ushered into a distant background, behind the flag and banners of patriotism.

Those who dare to call into question political leaders’ rationale for military action are often repressed or marginalized. One of the more notable cases was MSNBC's termination of Phil Donahue for airing voices critical of the Iraq war on his popular news commentary show.

War as Cinematic Abstraction

For most of us, warfare is a cinematic abstraction. War is something that happens on the big screen, and the big screen is where most of us learn what war is like. This isn’t by accident, either. As shown in the documentary, Theaters of War: How the Pentagon and CIA Took Hollywood (2022), the Defense Department actively works with movie makers to ensure a particular vision of the U.S. military and warfare are presented.

Established in 1948, the Pentagon's Entertainment Liaison Office has supported hundreds of movies including Top Gun (1986), Zero Dark Thirty (2012), American Sniper (2014), four of the Transformer movies, and two of the Iron Man movies. The 2012 movie, Act of Valor (2012), was initially intended to be a Navy recruitment advertisement. The filmmakers and the Navy soon partnered to turn the planned ad into a full-length feature film. The movie uniquely featured active duty U.S. Navy SEALS and U.S. Navy Special Warfare Combatant-craft Crewmen.

The military attempted to persuade producer Jerry Bruckheimer to alter the backstory of Bruce Willis’ character in Armageddon (1998). "The incorporation of an Air Force-related 'back story' for [the Willis character] could provide us the incentive to recommend official support of this project." Bruckheimer bucked the request and was still able to secure support. Undoubtedly this was partly due to the fact filmmakers consented to making other script changes suggested by the military. According to an Air Force memo, those changes led to "much greater Air Force presence in the film than was initially scripted."

In 1996 the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) established a similar entertainment office. Communications professor, Roger Stahl and his research team has unearthed evidence that the pentagon and the CIA have “exercised direct editorial control over more than 2,500 films and television shows.” Reflective of the increasingly intertwined relationship between government agencies and entertainment production companies, Jennifer Garner, who plays a CIA agent in the TV series, Alias, stared in an actual recruitment video for the CIA.

Denied Support

The Pentagon’s entertainment office has also denied support to movies officials deemed objectionable—films like The Deerhunter (1978), Apocalypse Now (1979), It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), GI Jane (1997), Platoon (1986), and Jarhead (2005). The defense department’s tax-payer supported monopoly on very experience state-of-the-art and military hardware gives the organization significant leverage over film productions. Producer Jerry Bruckheimer is on record saying that Pearl Harbor (2001) and Top Gun (1986) could not have been made without military support.

In his groundbreaking book, Operation Hollywood: How the Pentagon Shapes and Censors the Movies (2004), journalist David L. Robb writes,

"Over the last fifty years, hundreds of films have gone through the military's approval process, leaving the Pentagon's cutting-room floor a graveyard of deleted dialogue, eliminated characters, and cut scenes. Entire movies have been scrapped because someone in the military didn't want them made."

The pentagon denied Oliver Stone's request for support for Platoon for reasons including the film’s depiction of U.S. soldiers murdering and raping innocent Vietnamese villagers. Reading the details of the denial letter for the first time, Stone responded, “Well, I saw both.” Stone not only directed but also wrote the screenplay for the film based on his combat experience as a Vietnam veteran. As the Defense Department reports, Stone earned a Bronze Star Medal for valor.

From Stone’s vantage point, the Pentagon’s entertainment office is less interested in accuracy than clouding the realities of war.

“The whole ethos of that office, Pentagon, is that they're supposed to provide accuracy to the filmmakers, accuracy. And they do the opposite. They provide inaccuracy and lies. You show the bad side as well as the good side. We keep making military movies, especially since 2001, glorifying the American soldier, glorifying our patriotism, nationalism, homeland, all this nonsense. We make it into this fetish. We fetishize the military. No one can say a bad word about them. This is wrong. This is wrong. You have to point out evil when it happens.”

Amidst the rise of films like Top Gun, retired Navy rear admiral, Gene R. La Rocque, who commanded a nuclear cruiser and later founded the Center for Defense Information in 1971, expressed similar disapproval. In 1986 he told a reporter that he objected to Hollywood’s distorted portrayal of war.

“We can watch these films, see people get killed in war, turn off the set and then go get a beer. It is almost like a fairy tale. I hate these films. They glorify war and militarism. And that’s dangerous.”

Pentagon Propaganda?

In a 2020 interview with Military.com, Air Force veteran and current Director of Entertainment Media at the Defense Department, Glen Roberts explained that his office evaluates movies with an eye for “security, accuracy, policy and propriety.” The emphasis on accuracy is clearly secondary to maintaining and projecting a marketable image. Roberts admits as much when he says his office asks the question, “Is it the right way that we want to represent ourselves in the public eye?”

The decorated combat veteran turned novelist and, later, senator, James Webb, learned that the entertainment office’s prioritization of image over accuracy when he sought to turn his book, Fields of Fire (1978), about a group of Marines fighting in Vietnam war, into a film. The Marine Corps had made the book assigned reading so Webb, who was Navy secretary under President Ronald Reagan, was surprised when the Pentagon’s entertainment office denied his 1993 request for material support to make the movie.

The office explained that they denied Webb’s request for support because "the Marines and the Department of Defense would be tacitly accepting [criminal activities by soldiers] as everyday, yet regrettable, aspects of combat." Webb, who is a staunch supporter of the U.S. military and objected to Stone’s depiction of the United States and its soldiers, responded to the rejection by stating that the aim of making the film was to honestly depict events of the Vietnam war. He wrote:

“It appears that what you are really saying is that when it comes to Vietnam, [Department of Defense] will support only sterile documentaries, or feature films that amount to nothing more than dishonest propaganda.”

Law professor, Jonathan Turley agrees that the military’s entertainment office contributes to what must be recognized as a propaganda system. In the foreword to Robb’s book, Operation Hollywood, Turley writes:

"Like other propaganda systems around the world, the efforts of the military are often quixotic and comical in resisting well-known historical facts. Yet, in comparison with other countries, the U.S. military operates perhaps the most sophisticated and successful propaganda system in the world. These liaison offices work to influence public opinion on the margins and to reward script writers and directors who yield to their demands on the contents of scripts."

To claim the Pentagon’s actions are a form of propaganda is a serious accusation. The term propaganda is often bandied about in a diffuse and imprecise manner. Certainly the military does not exercise control over movies the way authoritarian governments like North Korea might. But propaganda, or the manipulative direction of others’ thoughts and actions, need not be so didactic to be successfully employed.

An early pioneer of the field of public relations, Edward Bernays’ book, Propaganda (1928), defended propaganda as a vitally important mechanism for controlling the public mind.

“The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country.”

Edward S. Herman and leading global intellectual, Noam Chomsky, developed our understanding of the unique exercise of propaganda in the media culture of our free society, in their book, Manufacturing Consent (1988).

Though journalists are not hindered by government censors, they are hindered by spoken and sometimes unspoken rules about the points-of-view they are expected to adopt. Those who adhere to the values and interests of those in positions of power, within the organizations and ownership hierarchy, are more likely to succeed and flourish. Those who think and report independently are less likely to do so. Phil Donahue’s previously mentioned experience is a clear example of this. Yet such firings are often unnecessary since those who rise to such heights of success have usually internalized the values and behaviors that are more likely to sustain their adherence to the dominant belief system, along with developing the circles of human relationships that reinforce that worldview.

The phrase “manufacturing consent” can be traced back to political commentator, Walter Lippmann’s book, Public Opinion (1922). Lippmann argued that democratic governance now required those in positions of power and authority to master and deploy the art of “the manufacture of consent,” the art of subtly directing the general public to reasonable thought and action on matters beyond their expertise. One way to produce the consent of the public for a particular order of society, according to Lippmann, is to shape the fundamental beliefs people rely upon to make sense of their world. He wrote that we by and large “pick out what our culture has already defined for us, and we tend to perceive that which we have picked out in the form stereotyped for us by our culture.” Those who shape these basic pictures of the world will, in turn, shape how we see and operate in the world. This influence will not feel oppressive or coercive. Instead we are likely to take our thinking and actions to be our own, even when they have been carefully scripted and directed behind the scenes.

More Than Meets The Eye: Hollywood, the U.S. Military, and the Manufacture of Consent

We see the manufacture of consent in the way the Pentagon actively develops relationships with movie makers in order to shape the works they produce. Though this does not constitute naked authoritarian propaganda, it does reflect the subtle art of manufacturing consent to a particular worldview to the exclusion of other competing perspectives and values. The leader of the Pentagon’s entertainment office readily admits to developing relationships with movie makers in the hopes of shaping their craft. Roberts said:

“we've actually sat down in writers' rooms with, you know, screenwriters and production teams to help strengthen and add credibility to their stories.”

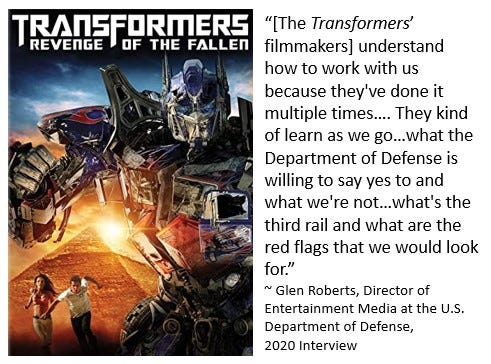

Roberts gave the makers of the Transformers movie franchise as an example of Pentagon-Hollywood success.

“[The filmmakers] understand how to work with us because they've done it multiple times…. They kind of learn as we go…what the Department of Defense is willing to say yes to and what we're not…what's the third rail and what are the red flags that we would look for.”

According to the Air Force, Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen (2009) is the culmination of more than one year of collaboration with the Department of Defense. That collaboration led to the military’s assistance in writing the script and the inclusion of military hardware such as jet fighters, an aircraft carrier, and Abrams tanks. Hundreds of service members from all four branches of the military were also featured in the filming to make “to make the film feel more realistic.” Parts of the movie were even filmed at at U.S. airbases.

The 2004 documentary, Operation Hollywood: How the Pentagon Shapes and Censors the Movies, offers a candid look of how the Department of Defense shapes movie making in Hollywood.

Though Roberts and others in the entertainment office deny that they actively dictate to movie makers what to do, they freely acknowledge developing relationships that indirectly exact profound influence over movies and the way they represent the military. One way the military develops these relationships is by taking entertainment workers on retreats. Roberts said

“the Navy does a program called Hollywood to the Navy, where on weekends, they'll take reporters or civic leaders or people in the entertainment industry, whether they're writers or producers, directors, actors, location managers, and drive them down to San Diego and show them around destroyer or a sub or an aircraft carrier….Take him out, see some, some aircraft, show them Special Forces that are…down operating down in that area. And it's just a great way to get the imagination flowing.”

We would all do well to recognize that when we go to the movies, we are often going with the pentagon.

Roberts also says that in addition to staying in consistent touch with the Writers Guild, the entertainment office takes industry leaders on immersive experiences. One example is when they flew about 40 people to Alaska and put them through an artic survival training school.

“They had to endure sub-zero temperatures just for a few minutes just to get an idea to get a taste of what the military folks are going through. They got to see F-22 fighters, they got to see the Air National Guard, combat search and rescue folks in action. So it's really an immersive experience…. It's fun for them to see and… to meet each other…, make those connections in the industry as well…. I keep in touch with all the various folks over the years…who…just continue to rave about those kinds of experiences.”

It’s important to recall that these experiences are funded by the U.S. taxpayer, and they have a purpose. The purpose, as Robb and others have shown us, is to shape the Hollywood representations of the U.S. military in order to shape the public’s perception of the military. The obvious question is whether or not the perception they intend to promote is accurate or in the interests of veterans and the wider public. At a minimum we would do well to recognize that when we go to the movies, we are often going with the pentagon.

If you enjoyed this post please share it with others and like it by clicking the heart icon. Be sure to subscribe if you haven’t already.

Invite Dr. Nall to Speak

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook or by leaving a comment.