Knowing When the Sky Isn't Falling: What an Ancient Fable about the End of the World Teaches Us About Critical Thinking

Part III in a Series Exploring the Art of Critical Thinking in the Pursuit of Living Well

Most Westerners know the European folk tale about a chicken stirred into frenzied action after a purportedly ominous object falls from up above. Far fewer of us know the more ancient fable from the Buddhist tradition. Both offer warnings about the dangers of group-think and decisions guided by fear. But the Buddhist fable, “The Sound the Hare Heard,” uniquely offers us a model for how to think critically as well as implied criticism of uncritical, fallacious thinking. The Buddhist tale also adds the keen insight that critical thinking requires ethical awareness.

Most of us know this tale as the story of Chicken Little or Henny Penny. The Danish scholar, Just Mathias Thiele, put the tale into print in 1823, centuries after being orally transmitted. In 1840, the illustrator and wood engraver, John Greene Chandler, told the tale to an American audience under the title, The Remarkable Story of Chicken Little, changing the protagonist’s name from Kylling Kluk in Thiele’s telling to Chicken Little.

In Chandler’s rendering, Chicken Little cries out that the “sky is falling” after something falls onto her tail. When her acquaintance, Hen Pen, asked how she knew the sky was falling, Chicken Little said she not only heard the sound of the sky falling but saw it with her own eyes. Hen Pen accepts Chicken Little’s subjective testimony, and insists that the pair “run as fast as we can.” Before long they are joined by Duck Luck, Goose Loose, and Turkey Lurkey.

Events turn fatal when the frantic flock reaches Fox Lox. Once the birds explain that the sky was falling, Fox Lox urges them to take shelter in the fox’s den.1 As they do so, Fox Lox bites off the head of each guest at the entrance of the cave, one by one, before devouring Chicken Little on the spot. Chicken Little and the rest of the gaggle don’t live long enough to learn that the object that fell from the sky was nothing but the leaf of a rose-bush. Unbeknownst to them all, their fear-based inferences and group-think led them not to safety but to the den of their demise.

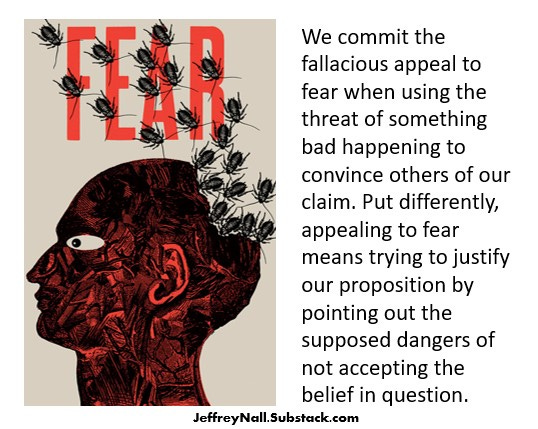

The 19th century telling of this tale leaves us with a clear warning about not just the dangers of accepting a claim because many in our community believe it, but also the error of allowing fear to influence our reasoning. We commit the appeal to fear fallacy when we determine what’s true based on what frightens us. The fallacy, as it’s expressed in the Chicken Little story, is this:

“If the sky falling would kill us where we now stand, we ought to believe the sky is falling and run!”

Appealing to fear means assigning a claim more credibility because of how terrible or dangerous it would be, if true, rather than deciding whether or not there is good reasoning or evidence for believing the frightening claim in the first place.

A common version of this fallacy is ubiquitously displayed along the interstate roadways of Florida where billboards urge passengers to believe in God to avoid an eternally burning in hell.2 But the purported dangers posed by God’s existence (for the unbelieving) is secondary to the question of whether or not God exists just as the risks posed by a falling sky can only merit rational attention once the claim that the sky is falling is proven.

To be sure, appealing to fear is a favorite tactic of manipulation. But it’s vital to recognize we can inflict this kind of irrational thinking upon ourselves, allowing fear to override reasoned judgment about the facts. This is represented in Chandler’s story, where the malevolent fox opportunistically fed into the fear of the birds who had convinced themselves that the end of the world was upon them. Their irrational thinking made them easy prey for the unscrupulous fox.

The moral of this story should not be misconstrued as an objection to any and all claims of catastrophic import. Sometimes the facts support terrifying and life-altering conclusions such as the reality of climate change or the jarring determination that a country we identify with is committing war crimes and ethnic cleansing.

The essence of the fable is that we must not allow fear to trump reasoned judgment in shaping our conclusions. The fear evoked about the claim in question is not evidence that the claim is true. Something does not gain credibility the more we fear it. Rather our fear should rise in proportion to the reality of the danger. And by knowing when the sky isn't falling we are better poised to handle those genuine calamities that life inevitably assigns us as individuals and members of society.

The Hare Before the Chicken, the Lion Before the Fox

Some 2,000 years before the Chicken Little story was put into print, Buddhist authors wrote what is perhaps the oldest of the sky is falling stories titled, “The Sound the Hare Heard.” The fable is featured in the Jataka Tales of the Buddha, written sometime between 300 BCE and 400 CE.

As implied by the name, the main protagonist of this ancient story is a hare and not a chicken. In place of a deceitful fox who takes advantage of the fear and gullibility of others, the Buddhist fable gives us an insightful and compassionate lion who seeks to help his fellow animals rather than prey on their vulnerability. The figure of the lion offers readers a valuable contrast between fearful and presumptive thinking and prudent, courageous analysis. More than identifying uncritical forms of thought, this ancient telling offers readers a model for how to think critically.

“The Sound the Hare Heard” begins with a group of monks asking the Buddha if there is virtue in the ascetics’ punishing spiritual practices of purification and self-denial. In reply, the Buddha says, “no,” and likens them to “the noise the hare heard.” Unfamiliar with the story, the monks ask him about this “sound” heard by the hare.

The Buddha then explains that there was once a hare who sat in reflection beneath a palm tree, wondering what would happen to him if the earth were destroyed. The hare’s meditation was interrupted by a clamorous noise from something falling from the sky unto the palm leaf under which he sat. Just as quickly as he jumped to his feet the hare jumped to the conclusion that the earth itself was coming to an end. “The earth is collapsing!,” he declared, as he took off into a run.

The hare’s alarm didn’t go unnoticed. Another hare demanded to know what the other was so afraid of. “The earth is breaking up!,” replied the first hare as he continued his sprint. Soon all of the hares joined the run, believing the world was crumbling. More and more animals became infected with fright. Deer, rhinoceroses, tigers, elk, boars, buffaloes, wild oxen, and even some elephants joined the panicked herd. The fearful group echoed the dire warnings they’d been told each time they passed other confused onlookers. And so the stampede grew larger as it rushed in the direction of the sea.

But not everyone was infected by the collective panic. The lion was skeptical that the earth was coming to an end and concerned that the other animals were going to hurt themselves. Inspired with compassion, he ran to the front of the stampede and brought the animals to a halt with three thunderous roars. The lion asked who had witnessed the start of this apocalypse. One by one, the animals pointed to the preceding group of species who had repeated the dire warning but had not themselves seen the earth collapsing.

“The tigers said, ‘The rhinoceroses know.’ The rhinoceroses said, ‘The wild oxen know.’ The wild oxen said, ‘The buffaloes know.’ The buffaloes said, ‘The elk know.’ The elk said, ‘The boars know.’ The boars said, ‘The deer know.’”

When the boars pointed to the deer, the deer in turn pointed to the hares. When the first hare to have heard the noise was identified, the lion asked where he had been when he witnessed the earth begin to break up. “In the forest in a palm grove mixed with belli trees,” he explained. “I was lying there under a palm at the foot of a belli tree.”

From these details, the lion concluded that the hare had probably heard the sound of a fallen piece of fruit and mistaken it for the earth’s collapse. But rather than rest with self-assurance in his explanation and simply report his hutch as fact, the lion “wanted to verify his conclusions and demonstrate the truth to the other animals.” He urged the frightened animals to calmly remain in their place, and then took the hare upon his back to the origin of the mayhem. The lion located the hare’s resting spot where the grass was still flattened. Nearby a piece of ripe belli fruit lay on the ground just beside the palm leaf the hare had been sitting underneath.

The lion returned to the others with the hare and shared not just his conclusion but also the evidence than led him to that conclusion. All that was found near the hare’s resting place was belli fruit, he explained, not fractured earth. The earth was intact and they could return to their routines without fear.

After the Buddha told the tale to the monks, he commented that it was the animals’ lack of independent thinking that put their lives in peril.

“Those animals had placed themselves in great danger because they listened to rumours and unfounded fears rather than trying to find out the truth themselves. Truly, if it had not been for the lion, those beasts would have rushed into the sea and perished.”

The Buddha concluded his lesson by revealing that he was, at the time, the lion.

Insights into Critical Thinking

The fable of the hare plants seeds to multiple insights for critical thinking. The first is also the most elementary and therefore easiest to overlook: that many of our strongest beliefs about the world are not based on direct experience or genuine knowledge; they are the result of a reasoning process that we too often leave to uncritical, unconscious determination. The hare believed he had experienced the onset of the earth’s destruction. As we know, his only direct experience was of a loud noise, which he interpreted to be the sound of the earth shattering.

We should be careful not to read the fable as a condescending critique of the hare. “The Sound the Hare Heard” is less about the hare than the intellectual egocentrism we’re all susceptible to. Like the hare, many of us spring to conclusions so quickly that it doesn’t even feel like we’ve participated in a thought process at all; it doesn’t feel like an intellectual act at all. The conclusion—that the earth was crumbling, in the hare’s case—feels so self-evident we can find it difficult to even explain ourselves. “It just is!,” we sometimes reply when pressed for an answer. And by insisting that the truth of our claim requires no justification beyond understanding the claim itself we commit the self-evidence fallacy.

Critical thinking, as the Buddha’s fable teaches us, begins with increased mindfulness or self-awareness. Namely, mindfulness of the thought processes upon which so much of our lives hinge. Like the hare, most of our mistaken beliefs have a kernel of truth. The hare, after all, did hear a loud noise. It wasn’t his ears that deceived him. It was the thought that such a loud sound could only be explained as the fracturing of the earth that initiated the ensuing panic.

By recognizing that few of our experiences directly reveal their meanings, we begin to ask ourselves what other ingredients have gone into making the stew of our conclusion. We become more attentive to the fact our understanding of the world is due to inference more than pure, passive observation.

Stand-alone observations are akin to puzzle pieces jumbled together with pieces of thousands of different puzzles. Putting the puzzle of life together requires much more than finding pieces of truth. It also requires deciding how to organize and piece those truths together in a coherent, sensible manner. Our experiences rarely gain substantive meaning before they’ve been filtered through a kaleidoscope of beliefs. When we allow this interpretive filtration process to be done uncritically and unconsciously, we effectively relinquish our agency and empower fear and whim.

Watch my short video, “Critical Thinkers Don’t Drop The Mic, They Pass It” at TikTok

The Folly of Intellectual Arrogance

Of course the hare’s conclusion—that the earth was collapsing—was preposterous. But we should be careful not to overlook the deeper truth conveyed in the story. All of us are prone to leaping to conclusions without so much as recognizing we’ve taken a leap at all. Too many of us are comforted by the thought that only fools are capable of believing preposterous things with the kind of vigor and conviction of the hare. Here we would do well to recall the French essayist, Montaigne’s insight that human beings are all fools.

“To learn that we have said or done a foolish thing, that is nothing; we must learn that we are nothing but fools, a far broader and more important lesson.”

We read a still more ancient warning about intellectual arrogance in The Dhammapada, where the Buddha taught his followers that the fool who “thinks himself wise” is the worst off of all. Such a fool is as impervious to receiving wisdom as the spoon is to tasting soup.

“The fool who knows his foolishness, is wise at least so far. But a fool who thinks himself wise, he is called a fool indeed.

“If a fool be associated with a wise man even all his life, he will perceive the truth as little as a spoon perceives the taste of soup.”

Understanding begins with the awareness of our limits and proneness to mistaken judgments about the world and also ourselves. It’s one of the most frustrating but also delicious ironies that many who most loudly lay claim to being the “rational” ones are often glaringly lacking in the basic self-awareness requisite for wisdom, and so present themselves as connoisseurs of soup in spite of the fact they are spoons.

“The Sound the Hare Heard” teaches us a lesson in intellectual humility. The animals were not stupid, but we're just too easily taken in by fear and groupthink to ask basic questions of an incendiary claim. We give ourselves too much credit to presume that we humans aren’t capable of such absurd folly. There is hardly a current event that splashes across mass media airwaves and news sites where we cannot observe passionate reactions from people who do not, first, take the time to examine the basis of the controversy they have so quickly taken sides on. When fear overtakes us there is little to no room for critical interrogation. This is because critical interrogation requires a courage that those consumed with fright cannot sustain.

Critical Thinking Entails Ethical Thinking

Lastly, we should note that the lion of this ancient “sky is falling” fable was more than an independent and judicious thinker; he was also empathetic. The lion was not a disinterested observer. His perspicuous assessment of the circumstances was inspired by compassionate interest in his fellow animals and the wish to mitigate unnecessary harm and suffering. In Psychoanalysis and Religion (1950), Erich Fromm commented that the primary reason he found the story noteworthy was that it signified the spirit of Buddhism.

“It shows loving concern for the creatures of the animal world and at the same time penetrating, rational understanding and confidence in man’s powers.”

Such a conception of critical thinking requires more than analytical skill for its own sake. The critical thinker’s deployment of reason and awareness, the Buddha and Fromm remind us, is animated by sensitivity and care for others, for life. For the powers of critical thought and reason to be more than mere “mechanisms” of manipulation, they must be brought into the service of our foremost values including a love of life and the living—of being and not only having. The true character of critical thinking is revealed not in the exploitative and ethically contradictory behavior of Fox Lox, who exploits the irrational fear of others in ways they’d never condone if directed at them. The marvel and character of critical thinking is observed in the Lion’s deployment of reasoned inquiry in the service of not only empirical truth but also ethical awareness that other beings such as ourselves—sensitive and capable of some degree of self-awareness—are worthy of care and help.

If you enjoyed this post please share it with others and like it by clicking the heart icon. Be sure to subscribe if you haven’t already.

Invite Dr. Nall to Speak

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook or by leaving a comment.

Neither the sex or gender of Fox Lox is given in the 1840 story.

The most common example I’ve encountered reads, “Where are you going? Heave or Hell?” Other examples, as identified by Jake Morow, include “Turn or burn,” “Stop, drop, and roll doesn’t work in hell,” “There’s no air conditioning in hell,” “Are you against Jesus? There will be hell to pay,” and “If you think it’s hot in the summer, imagine hell.”

This hits me as an attempt to minimize. Partly admittedly because I just posted a sky is falling post . I’m having a visceral gut reaction to the brutality and violence occurring on our planet . If only I could be just be a little more cerebral about all this .. the actual truth is that the sky isn’t falling as long as YOUR sky isn’t falling.

My sky is falling , your sky is falling if you believe that we are all connected. When the sky falls anywhere on the planet , or the roof caves in , or a child’s limbs are blown off. How much worse does it need to get , what would it take before it registers to you that sometimes fear is exactly the appropriate catalyst to realizing that the sky, indeed is falling .. what’s happening is a direct consequence of too many complacent people who stay in their heads critically thinking their way through what should be ripping their hearts out.