Quiet Joys Amidst an Alien Apocalypse

What "A Quiet Place: Day One" Teaches Us About the Good Life and What Makes Life's Hardships Worth Surviving

Note: The following exploration of the film, A Quiet Place: Day One (2024) discusses significant plot points that may be considered “spoilers.”

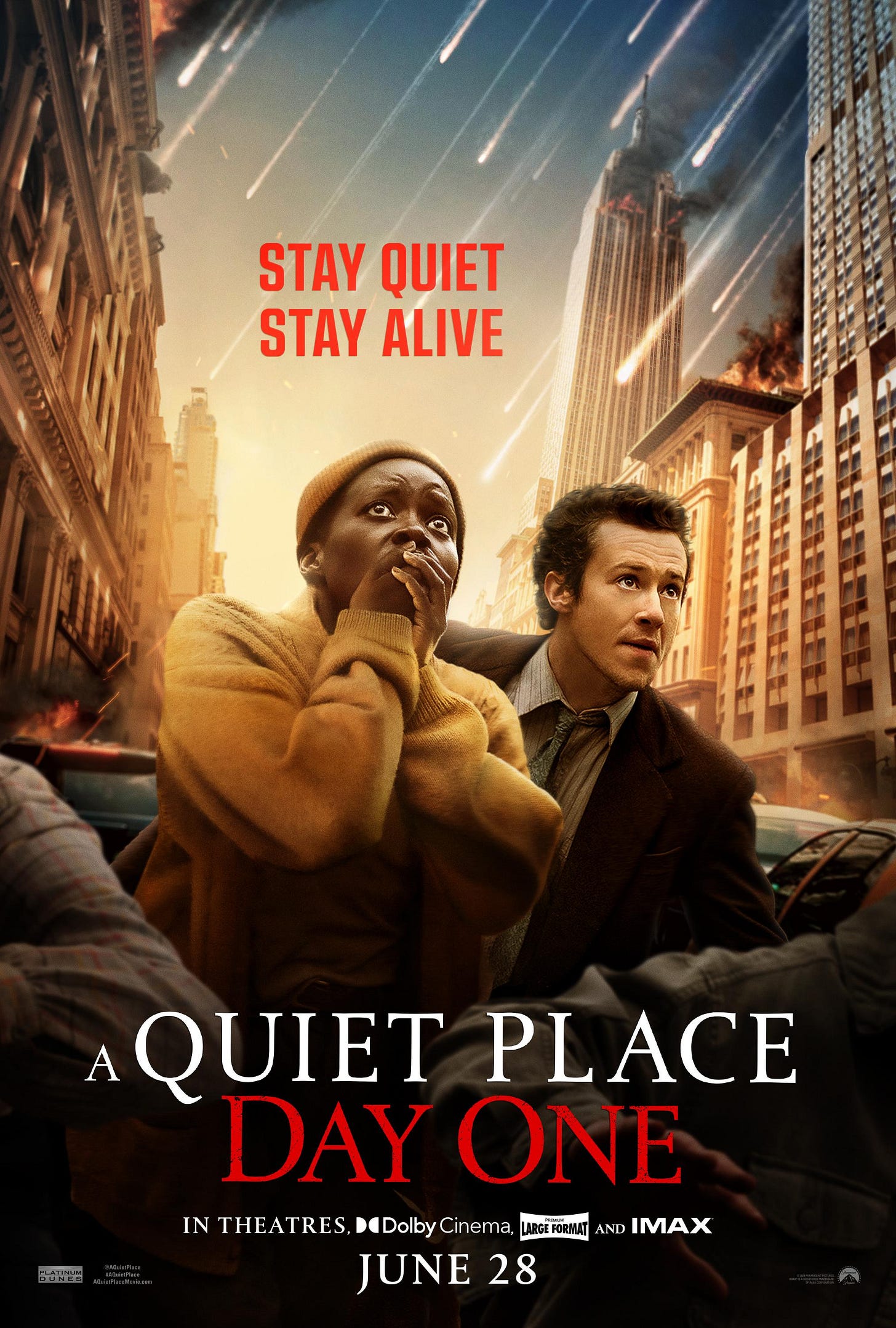

As did prior chapters of the film series, A Quiet Place: Day One (2024) gives viewers more than an action-packed, edge-of-your seat, jump-scare monster movie. We also get rich representation of the intrinsic joys of life, joys we sometimes numbly overlook in our narrow concentration on the future and what comes next. Day One helps us remember to live for the ends of life and not merely the means, that fulfilment is found in states of being more than those ruled by the clock and our possessions.

Most disaster or alien invasion films center on survival. Characters are presented with the challenge of preventing the total destruction of human civilization, if not the world itself, by aliens (Independence Day, 1996), an asteroid (Armageddon, 1998), a comet (Deep Impact 1998), the earth’s malfunctioning core (The Core 2003), a pandemic (Contagion 2011), or the malevolent use of climate-controlling satellites (Geostorm 2017). Day One is different.

The prequel to A Quiet Place I and II is not so narrowly concerned with survival or averting catastrophe. Like Seeking a Friend for the End of the World (2012), this is a film that takes up a question too many disaster movies take for granted: Why bother living in the first place? What is so good and beautiful in life as to make suffering worth surviving through? In helping us to reflect on such questions the film indirectly helps us appreciate why the impossible hardships life sometimes imposes on us may be worth trying to endure. In a word, this is a film that fosters clarity of mind and spiritual resilience.

Sam’s Quest for… Pizza?

The film’s protagonist, Sam, short for Samira, is terminally ill with cancer and living in a hospice facility. While Sam, played by actress Lupita Nyong'o, isn’t exactly running into the jaws of death, she's not exactly fleeing in terror from them either. It's not only that death’s menace has lost some of its terror, as she expressed in a poem her new friend, Eric, will later read, but life has also lost some of its glimmer.

Sam’s cancer diagnosis and impending death has made her numb to living and resigned to death. But this disposition changes when an apocalyptic alien invasion interrupts a reluctant trip into the city to see a “show” with fellow hospice patients—a show that turns out to be an oddly ominous puppet show of all things.

As the aliens rain down upon New York City, unleashing death, destruction, and chaos, Sam decides it's now or never to… get pizza. Her caretaker and friend at the hospice center, Reuben, played by Alex Wolff, thinks she's kidding when she silently conveys through pad and pen that she's going for pizza in Harlem. But she's not. And he can't dissuade her either.

Along the way Sam meets a kind and loyal puppy of a person named Eric, played by Joseph Quinn of “Hellfire Club” and Stranger Things fame. Viewers are introduced to Eric when he emerges from a sunken subway staircase as though he’s been reborn or escaped a watery tomb. He gasps for air in a state of panic before feeling calm as his eyes fall on Sam’s support cat, Frodo.

Eric is a law student from the U.K. and finds himself utterly alone in the Big Apple at the very moment he most needs family and friends. Eric’s panic is replaced by curiosity and bemusement as he follows Frodo through the besieged city. Eric soon discovers that Frodo isn't just out for a stroll but is returning to his/her caretaker, Sam.

Frodo may have a soft spot for strays but not Sam. She tries to send Eric on his way. She’s heading out for doomsday pie and an expedited appointment with death. Sam’s desire for pizza feels nihilistic as though little matters and she just wants to get the thing over already. In this respect Sam’s reticence and withdrawn attitude in Day One matches Dodge’s in Seeking a Friend for the End of the World, whereas Eric’s zestful optimism is like Dodge’s counterpart, Penny, in Seeking a Friend….

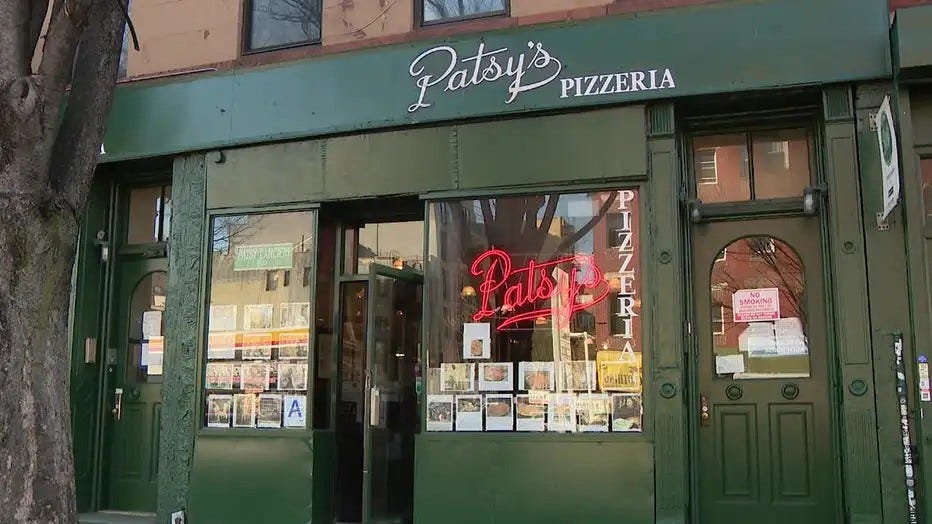

Seeing that Frodo has dragged along not a scrumptious mouse but a forlorn human, Sam gesticulates her disapproval, indicating that Eric should be headed in her opposite direction. When he gets closer she emphatically whispers instructions for reaching the ships—lifeboats for a land flooded by an alien horde—that the public has been told to board. But Eric is undeterred. He needs a friend more than he needs a direct route to safety, a consequential decision that ought to give us pause. He makes up his mind to help Sam get pizza. Specifically, pizza at Patsy's Pizzeria.

The bad news is that Patsy's Pizzeria is all out of fresh pizza due to having been burnt to a crisp. The good news is that Loetta's jazz club, where Sam’s father used to play piano still stands. It's here at the jazz club A Quiet Place: Day One displays its soul. (Interestingly, it turns out that Patsy’s is a real pizza restaurant in East Harlem NYC).

Timeless Joy Amidst Hell on Earth

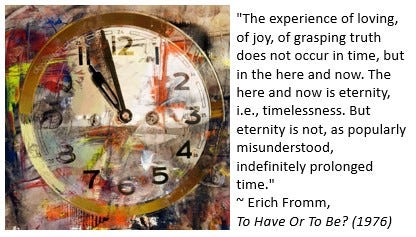

Day One reminds us time is not our possession and neither should it be our ruler. During the scene at Loetta’s, the filmmakers pause the harrowing action and give the characters time to eat, drink, connect, and play. We feel as though time is suspended or at least untracked as the characters dip their toes into the warm and immersive waters of being. Here Day One exemplifies Erich Fromm’s contention that we misunderstand eternity as “indefinitely prolonged time.” In his book To Have or to Be? (1976), Fromm wrote, “The experience of loving, of joy, of grasping truth does not occur in time, but in the here and now.” We experience eternity when we indulge our most cherished values and delight in our fullest humanity, our faculties of thought, feeling, creativity, and responsiveness to life. “The here and now is eternity,” Fromm wrote, “i.e. timelessness.”

Inside the club, Sam reveals that Patsy's pizza isn't really what she wants or misses the most. It’s her father who prematurely passed away before her own terminal diagnosis. Sam’s father used to bring her to his performances at the club and then take her for pizza at Patsy's, afterwards. Sam’s numbness to life, we discover, has been fed by not only her own senseless disease but also that of her father’s.

At Patsy’s, Sam’s cold, stiff, and crumpled up memories stretch out, reanimate, and grow nimble; her experiences with her father are liberated of time’s oppressive grip and return to her presently. She quietly runs fingers on the piano keys, perhaps the very piano her father once played. Standing in a silent and empty jazz club she once again experiences her father’s “beautiful” music. She sees his wide smile and feels the warmth of his presence. More than memories, these are intrinsically precious joys that make living good.

Narrowly centering our lives around sentimental memories and reflections on our past—“glory days,” as Bruce Springsteen described them—is part of what Fromm described as the having mode of existence, a passive manner of living that betrays the life it ostensibly glorifies. Those who live today exclusively on the stale and often distorted nostalgia of the past betray opportunities to live presently.

The key caveat is that we “can also bring the past to life,” wrote Fromm, rather than simply pining for what is no more.

“One can experience a situation of the past with the same freshness as if it occurred in the here and now; that is, one can re-create the past, bring it to life (resurrect the dead, symbolically speaking. To the extent that one does so, the past ceases to be the past; it is the here and now.”

While Sam enlivens her memories Eric, undeterred by Patsy’s destruction, sets out on a brief and undisclosed mission to find pizza to complete his friend’s experience. And he succeeds.

A whole pie has survived the invasion at the joint next to the jazz club. Returning to Loetta’s, Eric approaches Sam, turning his back to her to sweetly—but not deceptively—write “Patsy's” on the box, before delivering the pizza into her hands. Sam knows it's not the pizza her father used to get for her but it really is the thought—the experience, really—that most matters. She’s all too happy to sink her teeth into a slice and pretend it's the real thing.

Sam’s first bite tells us all we need to know about how long this pizza has been sitting out. Cold cheese, alas, does not stretch. And, what's more, pizza does not resurrect the dead. What it can do, even at its stalest, is bring us into the present if we are mindful. And so the two friends contentedly chew through cold, two or three day old pizza, washing it down with shared whisky or some other amber spirit.

Of course they would rather not be hiding out from sanguinary extraterrestrials hellbent on devouring humans. It's safe to assume they'd both jump at a microwave for the pizza and showers for themselves. Yet they refuse to be oppressed by the circumstances beyond their control. Thus they heed the ancient Greek philosopher, Epicurus’ dictate not to “spoil what you have by desiring what you don’t have,” and to remember “that what you now have was once among the things only hoped for.”1

Such a sentiment was shared by the Roman Stoic philosopher, Seneca who proclaimed “expectancy” to be “the greatest impediment to living,” for “in anticipation of tomorrow” we lose “today.” Sam and Eric do not make this mistake. They are at least presently satisfied with the experience of friendship, reprieve from alien terror, and satiation of hunger.

The jazz club scene affirms that eternity is indeed at the tip of our fingers. After eating pizza, Eric spots a pack of cards left at the club. Determined to extend their silent revelry he takes to the stage in dramatic fashion, pulling Sam up to assist with a magic trick. She selects a card, Eric blends them together, and then miraculously reveals the card she had secretly chosen. The two bow before an audience of empty chairs, their inaudible laughter radiating through wide, teethy smiles. This is a film where most of the acting is done not in reciting scripted lines but in expressing thought and feeling in body language and facial expression.

A Goal Greater than Survival?

A Quiet Place: Day One is not primarily about aliens, pizza, or unannounced magic shows. It's not even mainly about survival. This is a story of two people who respond to the threat of annihilation by an alien invasion by exemplifying the being mode of life. This is a film that resounds the insight of the ages that human fulfillment is not to be found in possessions, in having.

In the having-mode we numbly resign ourselves to taking in whatever life presents without active, enlivened thought or creativity. We treat living like a stale routine, a rerun of a show we watch just to “pass” or even “kill” the time. Our contributions are perfunctory, trite, and mechanistically premeditated.

There is perhaps no clearer portrait of the having mode of existence than the “documentarian” traveler. Such a traveler carefully documents the food, art, natural beauty, and historic sites so that they can preserve and recollect the sights and sounds—the experience. Their camera is always ready at hand. Yet such a traveler fails to mindfully experience the very objects, people, places, and events they are so determined to document! They are so ruled by concern for time and possessions—having or collecting photos, videos, souvenirs—that they sacrifice the very object that motivates their wish to possess and remember: being meaningfully alive to and engaged with the experience.

By contrast, when we are in the “being” mode of living we cease to experience ourselves and the world as a useful procedural step toward a distant objective—some vanishing horizon that moves as we step closer to it. Instead we experience the value of the world and ourselves for their own sake. “In the being mode, time is dethroned,” wrote Fromm; “it is no longer the idol that rules our life.” This does not mean we magically exist outside of time. The point, rather, is that when in the being mode we refuse to permit time’s alienating interference in our most cherished experiences.2

The true heroism of Day One’s main characters is that they refuse to be ruled by aliens, catastrophe, or even time. Sam and Eric exemplify the being state of existence even as they confront the inescapable reality of human mortality in the most direct and visceral way—murderous monsters occasioned to eat people from the face down.

Though the film initially turns on Sam’s peculiar hunger for pizza, we eventually learn that neither she nor Eric want any thing. The desires they most prioritize are existential. It's not a trivial fact that, for example, Eric performs his magic in tattered slacks and a dingy dress shirt and tie. We don't even learn of his capabilities until he spots the cards and launches into an impromptu performance. Even in desperate and desolate conditions his internal vibrancy of character spontaneously shines forth. He is strangely prepared for the end of the world precisely because of who he is and not what he possesses.

Eric’s manner of being is what it looks like when we cease to treat ourselves or others as vessels or things to use, manipulate, or even “profit” from. In the having mode “all that is alive becomes a thing” and “time becomes our ruler.” In being we embrace a full aliveness to the world: to the good and the bad, the beautiful and ugly; to the scent and taste of food, sound and rhythm of music, and sight of art; to birds, flowers, and sunsets; to human connection, suffering, and joy; to ideas, reason, and expression.

In the being mode we respect time, as Fromm puts it, but we refuse to submit to it. “By being I refer to the mode of existence in which one neither has anything nor craves to have something,” wrote Fromm, “but is joyous, employs one’s faculties productively, is oned to the world.”

The being experience activates our fullest consciousness and character to the simple yet profound end of joyous human experience, of communion with the living.

Day One's protagonist, Sam and Eric, exemplify humanity's embrace of the eternity and joy of “being” in defiance of time's tyranny and the instinct to recoil from life when faced with death. They respond to the alien apocalypse much like the man who was said to have encountered a tiger while walking through a field.

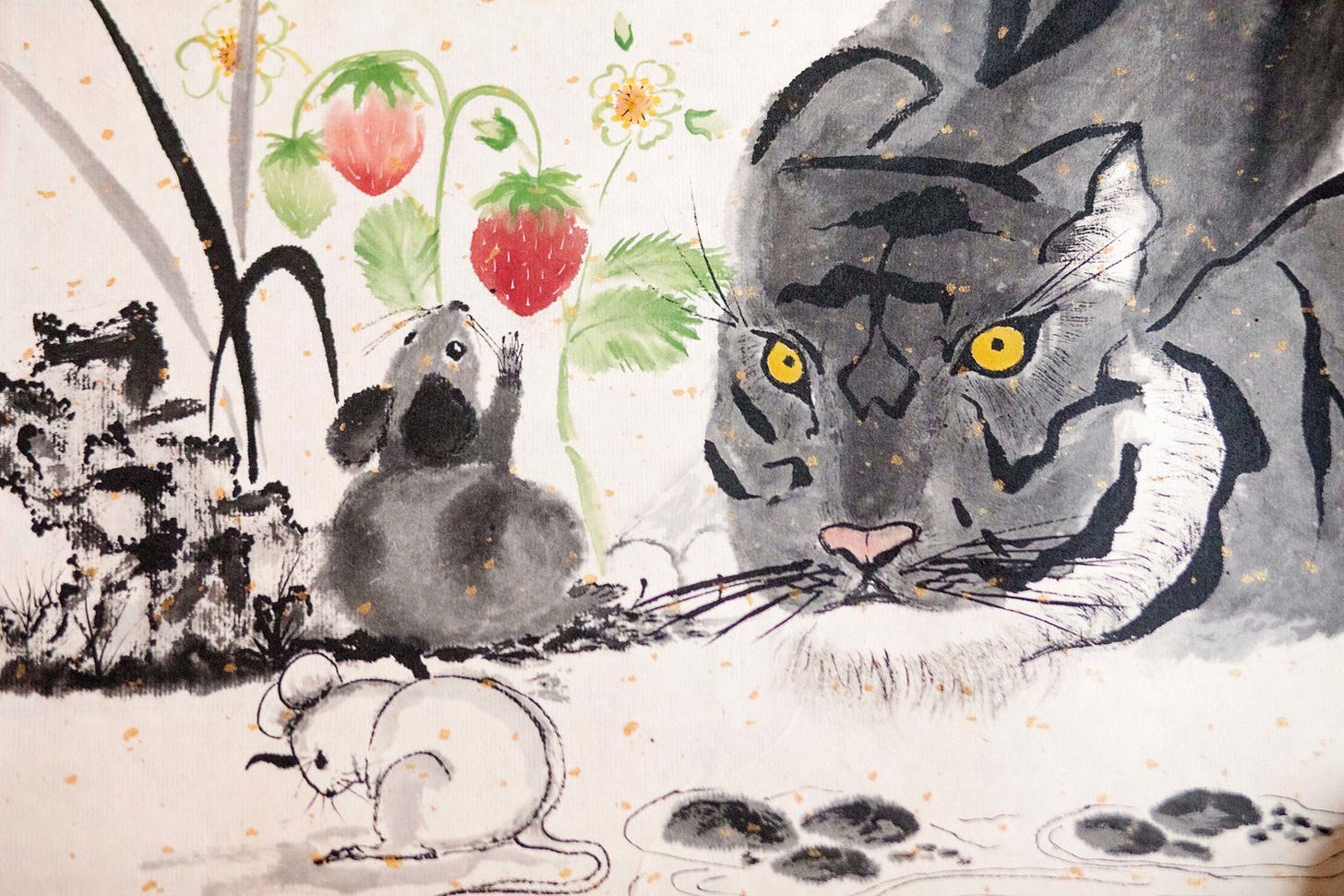

According to the Zen Buddhist story—a “koan”—the man who encountered a tiger did not flippantly abandon his life but fled in his best effort to survive. When he came to the edge of a precipice that was too high up to simply jump down from, he grabbed hold of a vine and climbed away from his pursuer. Frightened, the man surveyed his options and discovered he was not only dangling beneath one hungry tiger but also dangling above yet another who awaited him below. As two mice, one black and one white, begin eating through the vine—literally his lifeline—the man attentively recognized that a beautiful red strawberry sat serendipitously within his reach. With one of his last moments alive he chose to reach out and delight in the berry's sweetness. “How sweet it tasted!,” we read. The berry is the beauty of life amidst inescapable and sometimes unresolvable hardship, the sweetness that accompanies the bitterness.

Neither the point of Day One nor the Zen koan about the strawberry endorse nihilistic abandonment of life nor feckless resignation to bad circumstances. Instead, they invite us to ask how best to live as mortal beings precariously wedged between life and death. Part of the answer, I think, is to guard against being subsumed in “having”—of a life centered on accumulation and the mere manipulation of beings and objects for some ever distant goal—and to affirm the goodness of “being”—of creative, attentive aliveness to the world; of exemplifying goodness and virtue in the present rather than merely calculating its investment potential. To live well is to do more than escape aliens or tigers; living well means delighting in a strawberry, pizza, or a friendship for their own sake.

Returning to the jazz scene in Day One, we see that the fun of the magic show is a striking though complementary juxtaposition to an earlier scene at Sam’s apartment. She hasn't been home in a while and didn't have a key. Sam instructs Eric to kick down her door under sonic cover of cacophonous thunder. The first attempt is a glorious failure. Eric offers no pretense of the traditional masculine hero. He proves better at making Sam laugh and sensitively responding to her health needs than fending off aliens or kicking down doors. Care, not strength, is his virtue. Or rather we might say care is his strength. In any case, he kicks the door down on a second go.

At this point in the film, Sam hasn't yet decided to invite Eric over to Patsy's for pizza. In fact she tries to sneak out on him next morning only to turn around and see that Eric has caught her scent and looks to her with droopy “please take me with you” eyes. From that point the two friends are inseparable until the end of the film when Sam draws away the aliens so Eric and Frodo can make it to the rescue boats.

But back at the apartment the prior evening Eric found himself outside of Sam’s world even as he literally stood inside her home. That began to change when he found a book of poetry and confirmed Samira is the author.

She directed Eric to read the poem, “Bad Math.”

“He said one to two years

and it has been two.

He said four to six months

and it has been six.

And Mrs. Freelander

taught me subtraction.

And the corner store taught me addition.

And I used only simple maths

all my life.

And I never needed more…”

That was, until her doctor gave her one to two years to live. The simple math of elementary school and the corner store failed to prepare her for the countdown of terminal illness; failed to equip her to calculate the number of years, months, and days left with the icy breath of death moistening her neck.

And though Sam’s math is “bad” her poetry is quite good—evocative and illuminating. Eric now understands. Sam’s death is impending, and she doesn't know how to make sense of that portion of life measured by the last few grains of sand in the hourglass.

A Quiet Place: Day One reminds us of something all too easily overlooked: simple joys—of music, food, communion, play, not to mention poetry (Sam is a published poet)—give life it's meaning and therefore justify our efforts to survive through pain and suffering. These intrinsic joys—these “humanities”— also fortify us in such difficult endeavors. To survive at the cost of such joys would be to survive at the cost of our humanity, a pseudo survival indeed. Day One reminds us that surviving present adversity and making it to tomorrow only makes sense if our humanity remains intact.

By the end of the movie Sam has finally gotten her friend, Eric, and cat companion to safety. She walks through NYC with a newfound appreciation singing Nina Simone's “Feeling Good.” Though the filmmakers leave the very end ever so slightly open for interpretation, what becomes clear is that Sam has used the tragedy of the alien apocalypse to break with her cynical norm and rediscover the joy in living, even if only for a few days. What's more, her sense of fulfillment also readies her to fearlessly and joyously confront death.

Invite Dr. Nall to Speak

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook or by leaving a comment.

Number 38 in Epicurus’ Vatican Sayings.

As beings bound by time’s influence on our bodies, aging, and the “rhythm of night and day” we must respect time, as Fromm observed. The point is that in being we refuse to submit to it.

Wonderful review, not only of a film, but of the underlying theme of the film. Of the simple pleasures of life and of the joy they bring. The pleasures becoming greater and more pronounced when the choices are narrowed down to few, often one, such as one cold three-day old pizza. Too much choice can make one numb.

There is also joy in giving and in sharing, as in the giving and sharing between friends. I remember one time when we were going through a particularly hard time financially and someone gave my wife a gift basket that contained cheese, fruit jams and crackers. It tasted wonderful as we lived in the moment.

This is what Being is about. I never felt more alive, as I did then.

Thank you Dr. Nall. I have kept you in mind when I have some extra money. It seems unexpected bills seem to come often but will sooner, but will cease with the help of my dtr-in-law I hope. I love your discussion and words in the above essay and take them to heart. It is very difficult for me to live them but I try. If I didn't read your offerings I'd be the poorer for it. Your other commentaries on Life are equally valid and necessary to live by. With gratitude,

Bonnie A.