Part two of two exploring third party voting in the 2024 election and beyond. Read part one here.

The six third party candidates on enough ballots to theoretically win the 2024 presidential election are all but guaranteed to lose. Conventional wisdom goes further to insist that it’s self-evident that candidates who don’t win their respective campaigns are complete failures. The only rational impetus for seeking office is to win, and the only good reason to cast a ballot is to help ensure the best or least bad candidate among the two major parties prevails.

It’s clear enough who stands to benefit from this line of reasoning. If everyone conformed to such thinking, the political status quo would be maintained in perpetuity. And while such an approach to electoral politics is ubiquitous, it nevertheless overlooks both strategic and ethical reasons for third party voting.

Promoting Visionary Agendas

One strategic reason for third party voting is to challenge dominant parties’ ideological assumptions and encourage the public to embrace visionary agendas left out of the wider public discourse. In an August 2024 interview with The Take's Malika Bilal, pioneering consumer rights advocate

called into question the conventional view of third party voting as purposeless, idealistic, and ultimately counterproductive. “Historically the function of third parties in an electoral college system has never really been to win elections but to have new agendas,” he said. “The Liberty Party in 1840 launched the anti-slavery agenda. The women's suffrage parties in the 19th century pushed for women's right to vote. And then the farmer labor parties supported labor-farmer rights. Voices and choices come from third parties.”

Before the Civil War, anti-slavery activists launched the Liberty Party to oppose slavery. The Liberty Party drew in abolitionist supporters alienated from the Whigs and Jacksonian Democrats. Activists with the Liberty Party set the stage for the creation of a party that would lead the nation to abolishing slavery, Abraham Lincoln's Republican Party.

The movement toward building our nation's national healthcare system was brought about by the Socialist Party. At their founding 1901 convention, the party endorsed “accident, unemployment, sickness, and old age insurance.” These ideas were further brought into public light as part of the Eugene V. Debs’ presidential platform, with the Socialist Party, in 1904, 1908, and 1912. Debs lost each presidential bid, earning 3 percent of the popular vote in 1904 and 6 percent in 1912.1 But his presidential runs succeeded in challenging dominant political and social norms.

The party’s 1904 platform included a demand for “shortened days of labor and increase of wages,” “pensions for aged and exhausted workers,” and “insurance of the workers against accident, sickness, and lack of employment.” It also demanded “equal suffrage of men and women” and more mechanisms for the public to exercise control over their elected officials. During his fifth and final bid for the presidency, in 1920, Debs earned more than 900,000 votes—3.4 percent of popular vote—as he sat behind bars. Debs was serving a federal prison sentence for sedition for urging Americans, in a June 16, 1918 Canton, Ohio speech, to resist the military draft for World War I. With a willingness to endure personal sacrifice, Debs and his allies helped create conditions for future changes including the successes of the Farmer-Labor Party and the New Deal.

Formed in Minnesota, the Farmer-Labor Party (FLP) elected dozens of candidates to state and national offices in the first half of the 20th century. The group brought rural and urban workers together around the causes of strengthening the power of the labor rights and pushing for cooperative businesses and egalitarian policies. They joined president Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal coalition, helping to advance the expansion of social safety-net policies. In 1934, Governor Floyd B. Olson, a leader of the FLP, bucked the tradition of deploying the National Guard to break strikes by using the Guard to support unionized labor and relieve “the pro-employer and trigger-happy Minneapolis police force of its peacekeeping duties.”2 Ten years earlier, the party’s candidate for president, Robert M. La Follette of Wisconsin, challenged Calvin Coolidge and John W. Davis. Supported by Debs and W.E.B Du Bois, La Follette, nicknamed “Fighting Bob,” garnered more than 4.8 million votes and 16.6% of the vote and earned 13 electoral votes as he won his home state. La Follette used his presidential bid to demand public ownership of the railroads and utilities, an end to child labor, laws to strengthen workers’ rights, protection of civil liberties, and an end to U.S. imperialism.

And while the contemporary Green Party has failed to win any of its presidential bids the group has succeeded in shaping public and political discourse. The Green Party, which officially launched in 1984 at meeting in St. Paul, Minnesota—the state that gave birth to the Farmer-Labor Party—was a political forerunner in demanding action on climate change. The group conceived of the Green New Deal before segments of the Democratic Party embraced it. The party’s presidential candidates including Ralph Nader and Jill Stein have been among the most vocal critics of U.S. military policy, economic injustice, and the need for government accountability.

Along with independent candidate, Cornel West and socialist, Claudia De la Cruz, Stein has been among the most vocal critics of U.S. support for Israel’s onslaught against the Palestinian people in Gaza since 2023. She made headlines, in April 2024, after being forcefully arrested while attending a Palestinian solidarity student encampment at Washington University, in St. Louis, Missouri. She also made her opposition to the devastation in Gaza a central focus of her 2024 campaign, bringing the topic to the foreground in each of her numerous. Today, fewer than 50 years after its founding, Green Party members now participate in governance in more than two dozen countries.

Long-Term Party and Movement Building

Another strategic aim of third party voting is to maintain and enhance the viability of one’s preferred political party in future elections. Rather than seeing a presidential election as a one-off event, supporters of a particular party or movement may see their vote as a moment in a larger movement toward social progress. (Cornel West often stated he expressly conceived of his presidential candidacy as a “moment in a movement.”) Two concrete objectives in building a political party are gaining public funding and maintaining or growing ballot access.

Securing Public Funding

Presidential candidates who receive between 5 and 25 percent of the national vote are eligible to receive general election funds made possible through public funding. Given U.S. legal definition of “political party,” this opportunity to earn funding for subsequent election campaigns includes independent candidates.3 These funds are estimated by Green Party figures to be worth about $10 million. That is nearly double what Libertarian Party candidate, Gary Johnson, raised in 2016 and 250% greater than the amount Green Party candidate, Jill Stein, raised that same year.

Gaining or Maintaining Valuable Ballot Access

Many would have you believe the only way for a third party candidate to succeed is to “win” their election. What they don't know or care to mention is how small showings at the poll significant gains in ballot access, and thus lay the ground for long-term strategies of success. In Arkansas, Idaho, and Ohio for example, a political party that succeeds in gaining 3% of the vote for a presidential election is automatically qualified to add a candidate to the ballot in the subsequent presidential election. In Iowa and Wyoming, the threshold is just 2% of the vote. A third party candidate automatically qualifies for the ballot in New Mexico, Rhode Island, and North Dakota if they receive 5% of the vote in the prior presidential election.

Automatically making the ballot in this manner is essential for third party candidates. When a candidate is already on the ballot at the start of a campaign, they can invest their financial resources in campaigning rather than costly ballot access activities. One of the strategies employed the Democratic and Republican parties to minimize the impact of third party candidates is to overwhelm them with legal challenges, monopolizing both time and financial resources that would be more productively spent campaigning.

Those who accuse third party efforts of short-term political opportunism are either ignorant of the funding and ballot access objectives or choose to opportunistically ignore them.

Going to Rocks or Exercising Political Agency and thus Setting the Limits on Power

Another strategic reason for voting third party is to set limits on power by exercising political agency. Specifically, voters may choose to vote for third party candidates to penalize major parties and their candidates for exploitatively relying on their support without prioritizing their political concerns or responding to their demands.

Nader contends that voters affiliated with the major parties give up their political power by not conditioning their support. “[Engaged voters] can push the major parties and say, we're registered Democrat or we're registered Republican but we're going to condition our vote,” explained Nader. “We're not going to vote just because we're labeled Democratic Party voter or Republican Party voter. So they can begin by telling candidates, when they campaign in the communities, instead of just shaking hands and smiling with the candidates, they can condition their vote.”

Workers Strike Back cofounder, Kshama Sawant, said her organization’s objective in bolstering the Jill Stein campaign in 2024 is to “build the anti-war movement and working people's movement” and “fight to defeat Kamala Harris in a key swing state like Michigan.” On October 9th, Sawant stated, “Harris and the Democrats need our votes to win this election. They need this city. They need this state [Michigan]. We need to deny them those votes. This is the only language they understand. And the Democrats must be made to pay the price for being the party of genocide. Because if genocide is not a red line, then there is no red line.”

In an October 25 post,

made a similar argument. “Democrats ignore you precisely ‘because’ you vote blue no matter who: You know the adage, ‘a squeaky wheel gets the grease?’ How about ‘power concedes nothing without demand?’ Your compliance is ‘guaranteed’ to get you nothing.”Fans of the TV show Survivor know the power a group of players willing to “go to rocks” has. When the remaining players of the survival reality TV show cannot come to a majority opinion on who should be voted out of the group, those who did not receive votes are forced to randomly draw a rock from a bag. If you choose the wrong rock, you are eliminated from the contest and have the chance of winning the million-dollar prize. In prior seasons of the show, players have chosen to compromise with their opponents, jeopardizing their position in the game, to avoid going to rocks. But those players most willing to go to rocks immunize themselves from manipulative and coercive appeals to fear, and they force their opponents to negotiate with them on more advantageous terms.

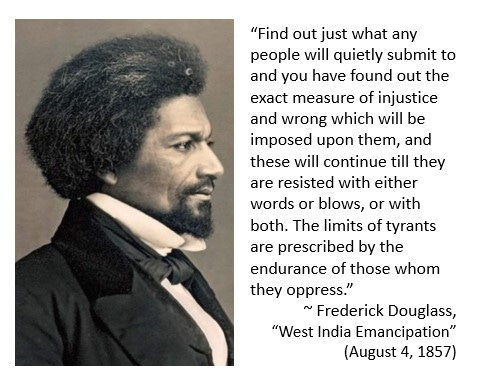

Advocates of voting outside of the duopoly argue that the major parties cannot be changed by those they hold hostage with fearful appeals of a “greater evil.” They point to the pioneering black abolitionist, Frederick Douglass’ observation that “power concedes nothing without a demand,” a statement that amounts to declaring a willingness to “go to rocks” or “go to the mat.”

A more precise picture of affairs was offered by Douglass just a few lines later in the same speech from which the statement about power not conceding without a demand was derived.

In his August 4, 1857 speech, he said:

“Find out just what a people will submit to, and you have found out the exact amount of injustice and wrong which will be imposed upon them; and these will continue till they are resisted with either words or blows, or with both. The limits of tyrants are prescribed by the endurance of those whom they oppress.”

Douglass’ point is that those exercising exploitative power will push those beneath them to the very limits of what they can endure. And if those burdened with such mistreatment acquiesce, they will be still more burdened and used. It is only when the exploited assert their agency that they establish limits to their abuse in relation to the unethical uses of power. But strategic games are not the only motivation for third party voting. Ethical reasons may be among the most important for many voters.

Ethical Considerations Beyond Lesser Evilism

One of the sources of misunderstanding around third party voting originates in presumptions about what it means to think ethically. For many, ethical thinking is synonymous with utilitarian thinking. Utilitarian ethics is a species of moral thought that decides what’s right or wrong based on the results generated from our actions. Act utilitarianism, in particular, insists that the right thing to do in any given situation is whatever will produce the best immediate results given the likely effects our action(s) will have.

From this perspective, it’s certainly conceivable that a voter would choose the “lesser-evil” strategy of selecting the least bad of two major candidates who are most likely to win. Such a strategy may not produce the ideal results, but it reduces the likely harm from indirectly depriving the least worst candidate running for office of our support.

Rule Utilitarianism

Intuitive utilitarians often overlook a different branch of this moral philosophy called rule utilitarianism. The rule approach challenges us to look beyond the immediate consequences of our actions. We are instructed to choose actions that conform to a happiness-maximizing rule or principle. This means that, when it comes to voting, we would be required to make a choice that was consistent with a general rule that if followed would make for a good society. The question would then be not only is a given candidate more likely to cause less harm than another candidate but would voting in such a manner consistently over time generate the greatest happiness? At least some will argue that a rule utilitarian approach to voting would have us embrace a longer-term strategy of building alternative political parties that better represent not simply the least bad but the greatest possible good.

Kantian Ethics

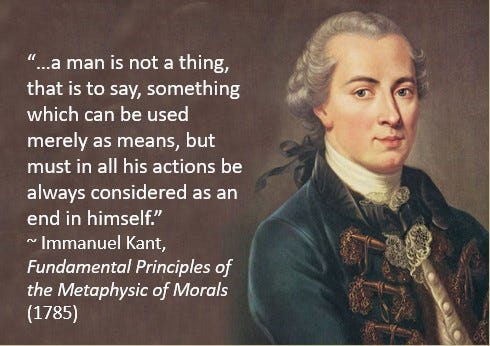

The problem is that this is just one of multiple ways to think about our moral obligations. Another ethical theory, Kantian ethics, emphasizes not the results of our actions but the nature of the actions themselves. Kantian ethics requires us to label as “good” or “right” only those choices that we could truly envision as universal rules of conduct, rules that we would rationally endorse becoming a kind of law for all of humankind. Lesser-evil voting takes on a different appearance beneath the light of Kantian ethics. For it forces us to consider the implications of always voting for the lesser evil candidate and never voting for our ideals.

At the root of Kantian ethics is the moral obligation to respect each individual person as intrinsically valuable. As Kant put it, “a man is not a thing…something which can be used, but must in all his actions be always considered as an end in himself.” Kant’s thinking matched the Talmudic statement, “Whoever destroys a soul, it is considered as if he destroyed an entire world. And whoever saves a life, it is considered as if he saved an entire world.” Such a standard of ethical judgment would have us assess lesser-evil voting differently than utilitarianism, particularly in light of the devastation of Gaza.

Logical Implications of Lesser-Evil Voting

Kantian ethics’ emphasis on the universalization of our thinking aids us in thinking about the logical implications of our actions. Universalizing a lesser-evilism approach to electoral politics that takes the existing options for granted, makes the transformation of our political system a logical impossibility. Consistently voting for the “lesser evil” of two candidates undermines opportunities for more “ideal” candidates and parties to emerge. To the extent that poor or corrupt governance generates social conditions that inspire political extremism, voting for the lesser of two evils to avoid short-term pain may only postpone the suffering. Worst still, the postponed suffering may in the interim accrue an even greater interest of pain for us to eventually endure.

This buck-passing strategy also presents some troubling implications when we consider past instances of social change. Whether the issue is ending slavery, ending segregation, or enfranchising women, the cause begins as impractical and unachievable in the short term. Genuine change only becomes possible or achievable when enough people refuse to embrace political fatalism and devote themselves to working towards a long-term goal of success.

Virtue Ethics

Virtue ethics, on the other hand, would have us change the question altogether. Instead of asking, “What should we do?,” virtue ethics would have us focus on “who we should be.” Virtue ethics advises us to think about the qualities a good and laudable person exemplifies, and then model ourselves after such an example. A person of such excellence would likely embody virtues—morally desirable habits of thought, feeling, and action—like justice, compassion, generosity, courage, integrity, and the like. Thus we are led to consider how someone exemplifying courage and integrity, for example, would respond to the electoral dilemma of choosing between an ideal third party candidate and the lesser evil candidate who is comparably more electable this electoral cycle.

Virtue ethics invites us to ask questions like, “What would Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. do?” Those inspired by the example of U.S. Airman Aaron Bushnell, who self-immolated in protest of the onslaught against the Palestinians, might ask, “Who would Aaron Bushnell vote for?”

How exactly such a moral lens would be applied to the question of who to vote for or whether or not we ought to support an ideal candidate unlikely to win or a lesser “evil” candidate is certainly up for debate. My point is just to highlight that morally analyzing our vote isn’t strictly a question of how to produce the “best results.” Some of us are also thinking about how to maintain our integrity and exemplify our most cherished values.

Care Ethics

Yet another ethical lens is care ethics. This is a moral lens that prioritizes human relationality and compassion in making decisions. An ethic of care interrupts the neat, mechanistic weighing of the dead to remind us of the sanctity of each and every life. An ethic of care might well endorse the red line of opposing any and all candidates that supply material and diplomatic support for the killing of children for the simple reason we would never support anyone killing our own children. A genuine ethic of care would make clear that Palestinian lives are not chips with which we are entitled to place our bets in hopes of securing better prospects for ourselves. Such “strategic” thinking may well be judged to be a vivid expression of American exceptionalism and unrecognized privilege.

More than hard-nosed demands, Nader believes voters gain political power by refusing to sacrifice moral principles and personal integrity for pragmatic calculation and worst-case-scenario avoidance. “I always say vote your conscience,” said Nader. “If you don't vote your conscience what are you voting? You're voting for least worst. Once you vote the least worst, you're in a trap and it never stops every 4 years. They got you. Because there'll always be a least worse. The only way you can pull'em towards honest elections that represent the interests of all the people, not the corporate supremacists and corporate lobbies, is to vote your conscience.”

When asked what advice he has to share with voters facing tough choices in 2024, Nader had this to say: “It depends on what's important for you. If the most important thing is to stop the US weaponization of Israeli genocide killing your relatives in Gaza and the West Bank, you vote for people like Cornel West and Jill Stein who have the best progressive agenda of any party candidates in the country. And if they're not on the ballot you write'em in.”

Please share and like this post by clicking the heart icon.

Invite Dr. Nall to Speak

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook or by leaving a comment.

Richard M. Valelly , '75. (2000). “Minnesota Farmer-Labor Party, 1916-”. The Encyclopedia Of Third Parties In America. 354-360.