Ten Million in Dissent: For the Love of Life and the Refusal to be Complicit

Remembering February 15, 2003, the Day the World Said No to War. Part IV in a series exploring the 2003 Iraq War

Read part I, II, and III below:

On February 15, 2003, millions of opponents of the United States government’s looming invasion of Iraq marched through the streets of cities across the globe. It was the largest coordinated mass protest event in the history of the world. The worldwide peace protest was additionally historic in that it took place more than a month before the bombs began dropping and tanks began rolling through Baghdad.

Though the peace movement failed in its aim of saving the Iraqi people from the carnage and catastrophe of the 2003 U.S.-led invasion of Iraq, we ought not overlook, ignore, or dismiss the noble and just efforts of millions across the world working together to honor human dignity and advocate for nonviolent conflict resolution.

We should acknowledge and contemplate the courage, civic responsibility, and critical thinking exemplified by principled opponents of the war. That the peace movement failed in its effort of averting the Iraq War is more an expression of the failing of our governmental institutions than the organizing efforts of the millions who passionately and rationally registered their dissent.

Preempting War

To make sense of the Iraq War and come to terms with the errors of our government we must remember that many elected officials, scholars, journalists, and ordinary people did forcefully oppose what was ultimately a misguided and catastrophic war. They did so months before the war, as the bombs fell. Once the war began, many sustained their efforts until the majority of combat troops were finally withdrawn in December 2011.

On February 14, 2003, U.N. weapons inspectors unequivocally reported that they had not found evidence of WMD in Iraq. The next day, opposition to the Iraq War reached its awe-inspiring zenith. On February 15, 2003, more than ten million people—10,000,000—united in worldwide protests against the invasion of Iraq. Citizens of 70 countries gathered in over 700 cities to demand U.S. leaders reverse its planned attack on Iraq. The coordinated global protest was the largest in human history as documented in vivid detail in Iranian-born British filmmaker, Amir Amirani’s film, We Are Many (2014).

As many as 1.5 million participated in London's anti-war protest. Protestors marched past Whitehall, Piccadilly Circus, and Hyde Park. British actor Mark Rylance described his joyous bewilderment at the diversity of the march.

“I thought I was on the wrong march. I did. I thought this must be for something else. Because there were all these families, people with push cars and babies. And people I just never see on these things. And the outpouring of rage from the people, it was so beautiful. Really passionate and eloquent and beautiful. People crying out and shouting.”

Rylance’s account indicates how awe-inspiring this expression and exemplification of peace and human dignity was to behold. For all of the excited cultural gushing over the “beauty” and “awesomeness” of masses of men gathered together to do war, we ought to interrogate the comparative absence of climatic celebrations and representations of such astonishing instances of love-potent solidarity.

For inspiration and a stretching of our moral imaginations we need only look to Spain on February 15 where at least a million marched through Madrid and even more marched through Barcelona.

We can also look to Italy where as many as three million marched against the war in Rome, rallying at St. John Lateran square. The protest is regarded as the single largest gathering of anti-war protestors in history, as of 2023. Consider how few know of this feet of coordinated human political effort. Remember that these are people gathered not to consume or to profit but to commune around their commitment to the preservation of human life.

Large peace protests were also held in in France, Germany, Czech Republic, Ireland, Greece, Italy, Ukraine, Norway, Mexico, South Africa, and Russia. Researchers in Antarctica once again joined the international protest.

The 2014 documentary, We Are Many, explores the February 15, 2003 peace protests and their consequence.

People in at least 150 U.S. cities participated in the international day of action. A quarter of a million marched in San Francisco and another 300,000 marched in New York City. Thousands more took to the streets in Washington D.C., Austin, and Detroit.

In New York City, the late singer and decades-long advocate of social change, Harry Belafonte, told hundreds of thousands gathered in protest that they were making history.

“Today is a historic and a proud day in the name of America. The world has sat by with tremendous anxiety and with a great fear that we did not exist. They had been told and they had felt that what our country, with its press and the leaders in the administration have said, we, today, invalidate all that. We stand for peace. We stand for the truth of what is at the heart of the American people.”

A growing number of artists followed Patti Smith’s example, joining the opposition to the Iraq War. Dozens of musicians across genres signed on to an advertisement campaign opposed to the war in February 2003. The group formerly known as The Dixie Chicks registered their opposition to the Iraq War. During a European tour, singer, Natalie Maines told an audience, “We do not want this war, this violence, and we're ashamed that the President of the United States is from Texas.” The Chicks faced significant backlash within the country music community, but were later identified as an inspiration for one of the most successful country-pop artists in the country, Taylor Swift.

Members of the heavy metal band, System of a Down, worked with filmmaker Michael Moore to create a music video for their anti-war song, “Boom,” from their 2002 release, Steal This Album. The music video was crafted to commemorate the February 15, 2003 peace protests. Band members are shown participating in the day of global protest along with images of February 15 protestors from around the U.S. and world. Throughout the video, protestors’ voices are cut in over the musical soundtrack as they sing lyrics to the song like these:

“Every time you drop the bomb

You kill the god your child has born

Boom, Boom, Boom, BoomModern globalization

Coupled with condemnations

Unnecessary death

Matador corporations

Puppeting your frustrations with a blinded flag

Manufacturing consent is the name of the game…”

Well-known musical artists including Pearl Jam, R.E.M., John Mellencamp, and the Beastie Boys created songs critical of war and/or the Bush administration. Such songs rarely found the light of day on corporate controlled radio airwaves. Artists like The Chicks were actively suppressed.

Hometown War Resistance

In 2003, I was part of peace efforts in my home state of Florida. At the time I was doing freelance journalism and interviewed a Florida activist with the Green Party for a local event she was participating in. During the interview she expressed concerns about the Bush administration’s rhetoric around Iraq and the prospects of war. I found her analysis and moral concerns compelling.

After writing my story I reached out to people where I lived in Brevard County, Florida, and organized a meeting of concerned citizens. The meeting was set for January 26, 2003, Super Bowl Sunday of all days. I had wanted to watch my state’s team, the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, battle it out with the Oakland Raiders. But we understood the urgency of the moment, everything else had to wait and Sunday was the best day to gather. In all honesty, I had no idea what I was doing. I had never organized a protest. Excluding the events my parents brought me to as a child, I had never even participated in a political action. As we often do in life, I learned as I lived—on the fly.

I was disturbed by the contrast of U.N. reports indicating that pregnant women, the elderly, and those in need of medical attention would be among the most immediately impacted by a U.S. invasion and an aerial bombardment. This was brought even closer to home for me because the mother of my eldest daughter was pregnant and expecting to give birth in May. Many of my friends and neighbors found mainstream U.S. media reports compelling. They were convinced Iraq had WMD and they were afraid. But I was skeptical. The reports were alarming in tone but lacking in evidence. I refused the appeals to power that were so prevalent amidst the frightening rhetoric of nuclear “mushroom” clouds. I understood, intuitively that being in a position of authority does not guarantee that the person in that position really “knew more than we did.” Still in my early 20s, I had learned enough to know that irrational faith in leaders had allowed many horrors to be perpetuated. I also saw that the international press offered a radically different understanding of affairs than was being portrayed by the U.S. media. The WMD question was not at all settled. Many questions remained, yet our nation was on a determinist path to war.

A small group of us gathered at the now defunct Green House Café in downtown Melbourne, Florida. We introduced ourselves, shared our concerns about the looming conflict, and went about planning a march in our community on February 15. We contacted houses of worship, civic groups, local political parties, elected leaders, and college students. We made flyers for the march and passed them at local events.

As with much of the larger public, many in our community were convinced by the administration's rhetoric and accompanying news coverage that a military attack on Iraq was necessary to keep safe. Some were outraged by our objections to the war. Still, many others were not convinced that invading Iraq and starting yet another warfront was strategically or morally right.

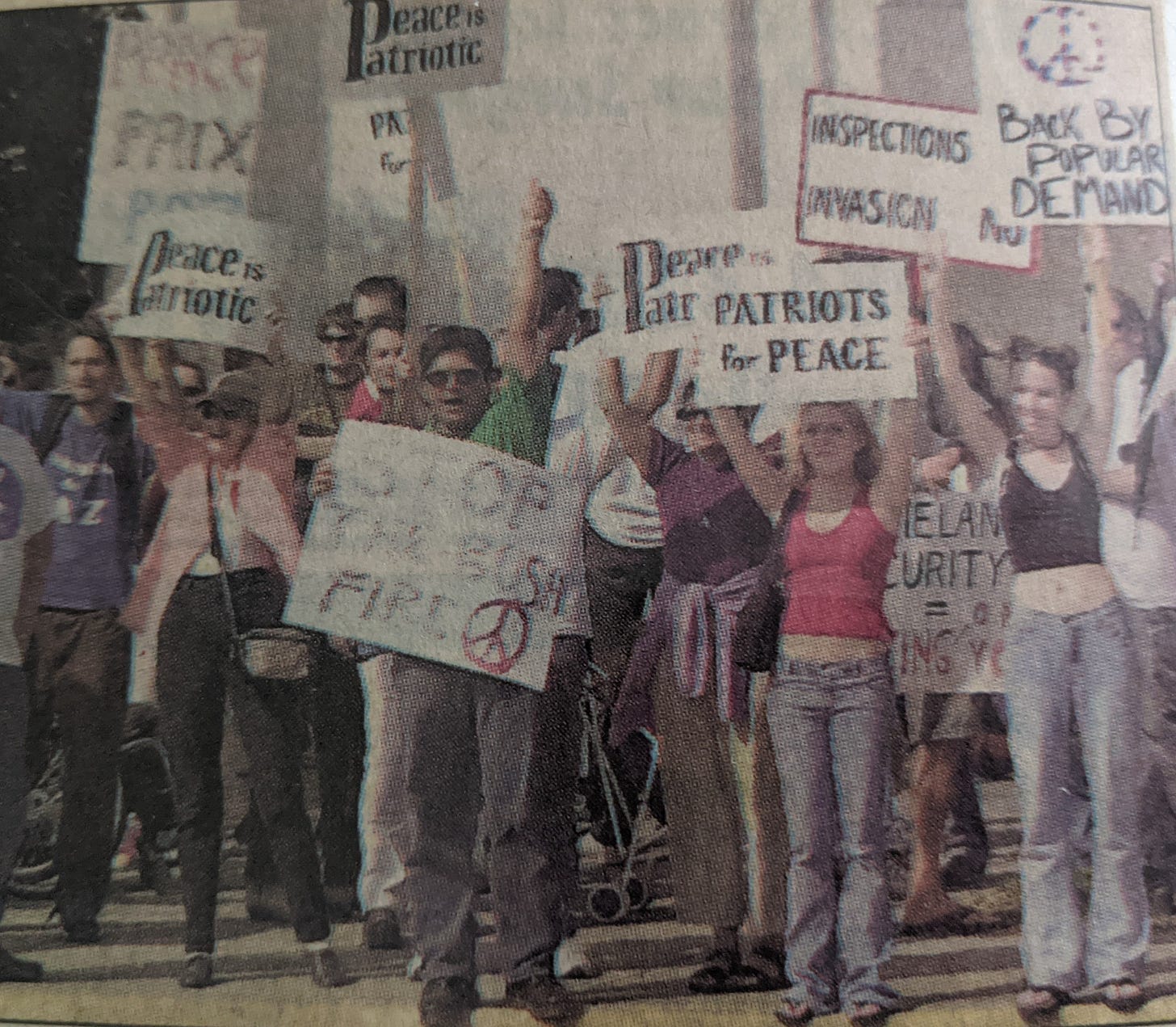

On February 15, 2003 about half a thousand people took to the streets of Melbourne, a city of fewer than 80,000 at the time, and marched to city hall. It was an event unlike any that had been held in the community. Our march brought out people from all walks of life: high schoolers, college students, working people, and retirees. We were joined by veterans, representatives of different faith traditions, and people of varied politics, from libertarians to socialists. World War II veteran, George Colburn who was 77 at the time told the local newspaper that the war was “completely unnecessary” and that the president had not made a sufficient case for invading Iraq. We were even joined by the folk singer, Arlo Guthrie, who lived in the area. Arlo, son of folk legend Woodie Guthrie, brought his guitar and gave an impromptu performance.

There was a joyous electricity in our coming together to advocate for the most basic of ethical precepts: the preservation of innocent human life and the insistence that our government be accountable to the governed. Our chants and speeches were filled with passion. We listened to elders in our community describe their efforts to stop the Vietnam War. We talked with our neighbors and people we would have otherwise wordlessly passed by in the local grocery store. We found a strange social space where talk of income and shopping was replaced with talk of values, dreams, and democracy. We made new friends and developed new insights. Little did we know, others around the world were doing the same.

We were joining millions of people across the world to collectively speak out against the administration’s plan to invade Iraq; a war that would become as costly to human life as it was erroneously based. It was the first of many local marches, rallies, and vigils held over the coming years with the aim of promoting awareness of the destructiveness of militarism and the U.S. policy in the Middle East.

Sustained Opposition to the War

Another remarkable feature of the peace movement was its resilience and determination. Opponents of war continued organized protest even as the media and pundit class resigned themselves to the “inevitability” of war. On March 16, just days before the launch of the invasion, cities around the U.S. held peace vigils. In Melbourne, Florida, our local peace group brought together about 200 people who braved growing intolerance for dissenting views about the war and Bush administration. As many more and more began treating war as a foregone conclusion, opposition to war was increasingly equated with opposition to “America” and “the troops.”

This sentiment was stoked, if not manufactured, by corporate and political interests backing the President’s lurch toward war. In March 2003, Clear Channel radio stations began promoting what the company called “Rallies for America.” The rallies, purposed to promote support for President Bush, were attributed to then Philadelphia talk show host, Glenn Beck, whose radio show was part of the company’s network. The rallies featured signs criticizing France and the Dixie Chicks.

Opposition to the Iraq War did not end when the invasion began. Even as it failed to prevent war, the peace movement persisted in the years to follow. Local groups worked with national peace organizations, including United for Peace and Justice, Veterans for Peace, Code Pink, and the Answer Coalition, to hold countless local, statewide, and national actions.

Even as the bombs were bursting in Baghdad, advocates for peace continued to rally and march throughout the U.S. and world. Many took to the streets the same day Bush launched the invasion. And doing so was not without consequences. For the next several months, opposition to the Iraq War was met with hostility and even threats as support for the war grew.

Opposition to the war was not limited to musicians, actors, veterans, and non-veteran citizens. A leading force in the opposition to the Iraq War came from soldiers who had served in Iraq. In July 2004, veterans of the war founded “Iraq Veterans Against the War.” The group gave voice to Iraq War veterans' experiences and moral objections to the war.

Some active duty members of the military refused to serve from the start. In April 2003, U.S. Marine, Stephen Eagle Funk became the first conscientious objector during the Iraq War. After deciding to turn himself after failing to report to his unit, Funk told The Guardian that he “would rather take my punishment now than live with what I would have to do [in Iraq] for the rest of my life. I would be going in knowing that it was wrong and that would be hypocritical.” Funk talked openly about the military's aggressive and violent culture, noting that some of his fellow recruits expressed jealousy that he was being deployed to Iraq. “They would say things like, ‘Kill a raghead for me - I'm so jealous.’” After six months of imprisonment Funk was discharged.

Families of the fallen also registered their dissent. Carlos Arredondo began protesting the war after his 20-year-old son, Alexander, was killed in Iraq on August 25, 2004. To work through the pain of his loss and express his opposition to the war, Arredondo later began travelling the country with a pickup truck containing an empty flag-draped coffin and a picture of his son's open casket, taken during his funeral.

In August 2005, Cindy Sheehan started an encampment outside of President Bush's Texas ranch, demanding that he speak to her. Sheehan's son, Casey, an Army Specialist, was killed in Iraq, in 2004. Sheehan decided to follow the president to his ranch after hearing him say that fallen soldiers had died fighting a “noble cause.” Sheehan insisted that Bush explain what that noble cause was. Her encampment continued for weeks, drawing several hundreds of supporters over the duration.

In 2004, the American Friends Service Committee launched an exhibit titled, “Eyes Wide Open,” featuring 504 pairs of military boots. The exhibit aimed to tangibly represent the costs of war which are sometimes hidden behind abstract statistics. In the years to come the exhibit would be expanded, reflecting the growing loss of life, and brought to as many as 100 cities in dozens of states.

Around the fifth anniversary of the war, March 18, 2008, I helped bring the exhibit to Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton, Florida, where I was completing my doctorate. Several local volunteers including anti-war veteran, Michael Prysner, helped unload the 1,000-pound exhibit and place 176 pairs of combat boots, each tagged with the names of soldiers from Florida who had died in the Iraq war. We also set out over 200 tennis-shoes representing the many thousands of civilians who had died. Many visitors were moved to tears, viscerally impacted by the loss of life vividly represented in the rows of empty shoes and boots.

The exhibit’s impact was a reminder of the power of creative symbolic expression to help human beings process feelings of grief and communicate otherwise abstract numbers in appropriately human terms. Many of the same people who might have numbly read through a daily news report of the civilian and military death tolls from the war could not help but feel the realities of the war's consequences more viscerally upon seeing the exhibit. So many empty shoes, so many missing people--loved ones.

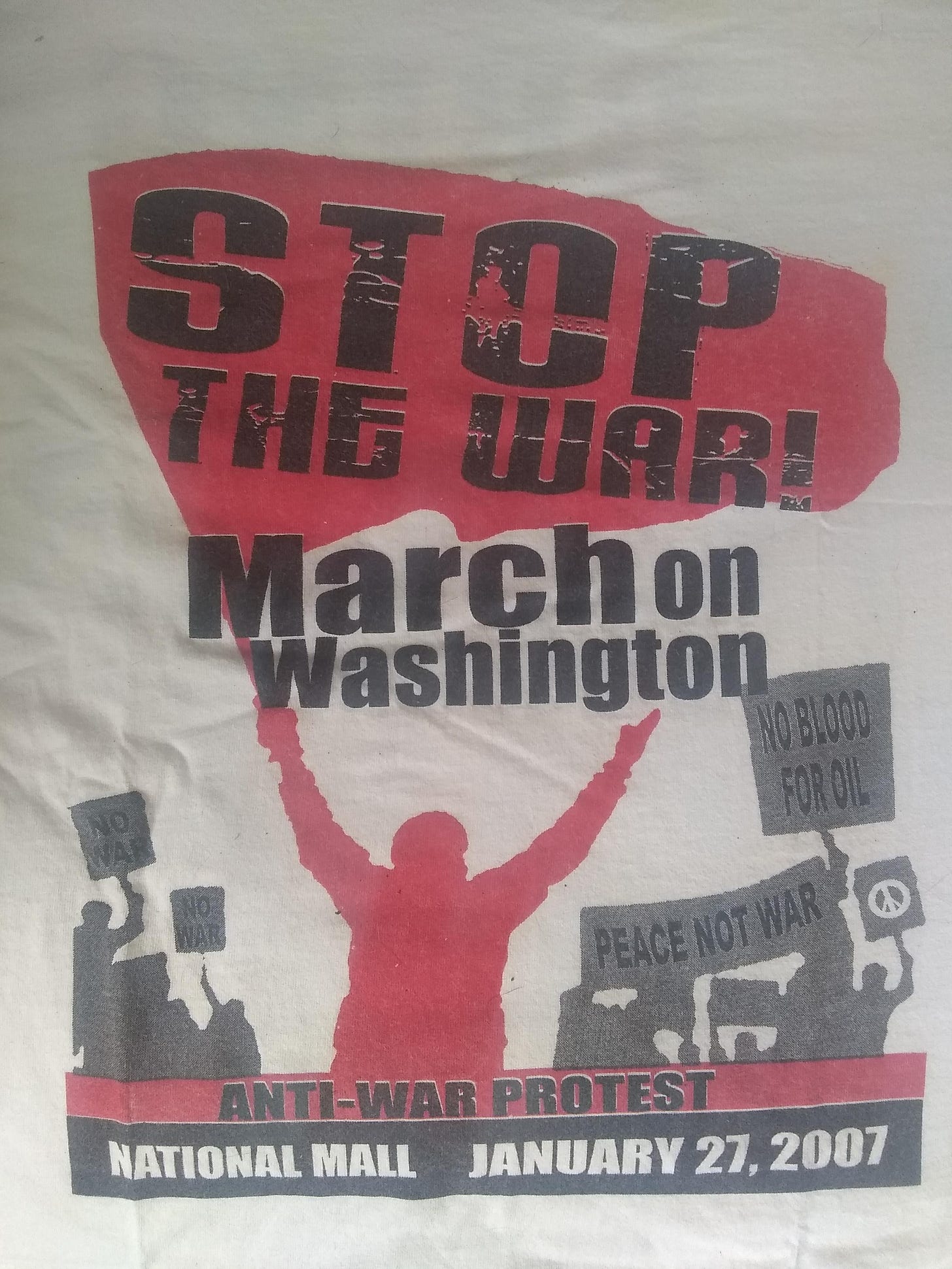

By 2007, the public was increasingly war weary and advocates for peace once more took to the national stage. On January 27, 2007, half-a-million people returned to Washington D.C. to march against the war in a protest organized by United for Peace and Justice.

The mobilization was in response to President Bush’s decision to deploy an additional 20,000 soldiers to Iraq. Protestors of all ages, including young people, children, and seniors, carried various signs, chanted passionately, and communed with one another, discussing the war and politics.

The January 2007 mobilization was followed by four more demonstrations in Washington D.C. and around the country on March 17, September 15, September 29, and October 27.

As many as 100,000 showed up for the September 15 demonstration in Washington, D.C.. Veterans across military branches joined determined activists in registering their dissent. Ken Hudson of Miami, Florida attended the protest with his son and friend. They all wore shirts honoring the life of Iraq War veteran, Christopher Hudson. “My little brother got killed over there three years ago [2004],” Ken told me during the protest. He said his brother was a gunner and died after running over an improvised explosive device in front of Abu Ghraib prison. “I was never political, ever. And then this happened to Chris.”

The September 15, 2007 protest was unique in that thousands participated in mass civil disobedience. During the march many participants insisted more needed to be done, that more direct action was required to challenge the administration’s ongoing war policy. At the end of the permitted march route thousands of protestors began climbing over the cement and iron police barricades. It was an electric moment of spontaneity. We knew that we were risking arrest. But the moral momentum of the moment was with us, so over we went.

The September 15 civil disobedience was distinct from violent and destructive takeover of the Capital on January 6, 2021. We laid down on the green grass surrounding the Capital building. We were nonviolently occupying the Capital grounds and insisting to be heard. It was a multigenerational “die-in.” Adorning a camouflage jacket and sun glasses, New Yorker Zach Hasychak reclined on his elbows, facing the Capital. “Something needs to be done and nobody else is doing it,” he told me when I asked why he was there. “I’m definitely willing to get arrested.” When all was said and done, those of us on the grass were not arrested. Police retreated to the Capital steps where nearly 200 people defiantly crossed barricades, nonviolently offering themselves up for arrest.

During 2008, the peace movement continued its efforts. Many individuals and groups expanded their efforts to combat the Bush administration provocations against Iran and the specter of yet another U.S. war. Protests were held around the United States calling for a diplomatic resolution of tensions between Iran and the U.S.

That same year, more than 200 veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan came together for the “Winter Soldier” conference, at the National Labor College in Maryland. Veterans shared personal accounts of their war experiences. Participants drew inspiration from the Drawing inspiration from the 1971 Winter Soldier Investigation in which more than 100 veterans of the Vietnam war gathered to discuss their experience and knowledge of war crimes.

One of the participants was Michael Prysner, an Army Specialist from 2001 to 2005, who was deployed in Iraq. Prysner described forcibly removing families from their homes and using force and intimidation prisoners. He said that “towel head,” “camel jockey,” “sand nigger,” and “haji” were used by not only fellow soldiers but also “all the way up the chain of command.” Thirteen years later, Prysner made headlines when he interrupted George W. Bush’s speech in Beverly Hills California, demanding that the former president apologize for “lying” the U.S. into war and leading to countless deaths.”

To ignore that so many ordinary people did think critically and independently is to give credence to the excuses of power for its failings. The tendency of power is to treat its "errors" as impossible to foresee. Millions recognized the Iraq War was based on erroneous claims and violations of basic ethical precepts such as universality. Many consistently voiced their objections before the war and once the Bush administration began the invasion of Iraq.

Who To Blame?

There is no disputing the fact that those participating in the peace movement failed to achieve the central objective of preventing the Iraq War. The February 15, 2003 worldwide march was followed by emergency rallies throughout the months of March and April. But the movement could not stop the invasion or occupation. The pain of this failure only grew as we learned more about the on-the-ground realities of the war. At least 280,000 civilians died as a direct result from the war, with many more thousands dying from indirect effects of military violence. Yet it would be a mistake to attribute the failure to stop such horrors to the peace movement.

The peace movement’s failure to prevent the Iraq War is best understood as a failure of the British, Australian, Polish, and U.S. systems of government to honor democratic representation. Asked about the February 15, 2003 protests a few days after they took place, President Bush said, “Size of protest — it’s like deciding, well, I'm going to decide policy based upon a focus group. ‘The role of a leader is to decide policy based upon the security, in this case, the security of the people.’” A truly representative government could not have so flippantly ignored the passionate and rational protests of so many of its people.

There is no way to know if the Bush administration and their allies in both parties in the Senate would have responded to a larger peace movement. But it is also not entirely unreasonable to imagine greater reluctance in the administration to proceed with the planned invasion had fewer people accepted the administration’s rationale for war. Rather than finding fault in those who did contribute to trying to prevent a factually misled war, we would be on better ground to locate fault in the failure of the larger public to critically examine the administration’s claim. We can find additional fault in the journalists in the mainstream press who failed to adequately scrutinize government claims and also amplified the administration’s unsubstantiated claims. It is difficult to imagine the war would have been pursued without at least tenable support from many millions in the U.S.

Peace and Biophilia

Furthermore, we ought not judge the meaning and value of the peace movement's efforts solely on the narrow basis of whether or not the Iraq War was prevented. Their efforts were more than means to stop war, they were exemplifications of human excellence and decency.

The peace movement succeeded in honoring universal, immortally venerable values—values that are not kept alive through perfunctory acknowledgment or academic reference. The individuals comprising the movement exemplified commitment to the love of truth, human dignity, democracy, and justice through actions opposing the war before and after the invasion of Iraq, including the largest global protest in human history on February 15, 2003, vigils for the war-dead, along with demonstrations against torture following revelations about explicitly necrophiliac abuses of prisoners at Abu Ghraib. However unintentionally, such efforts were part of an ancient and ongoing project of exemplifying, and therefore keeping alive, these sacred human values.

The peace movement both expressed and fueled biophilia: the preference for dynamic creativity and fatalistic resignation, communion over possession, the whole over the part, exemplification above posturing, spontaneity and aliveness over the perfunctory and mechanical, love and reason over fear-driven manipulation and force. As Erich Fromm explained it,

“The biophilous conscience is motivated by its attraction to life and joy; the moral effort consists in strengthening the life-loving side in oneself. For this reason the biophile does not dwell in remorse and guilt which are, after all, only aspects of self-loathing and sadness. He turns quickly to life and attempts to do good.”

The global peace movement embodied this intrinsically good love of life. It affirmed the universal love of humanity against the pressures to consent to war, allow fear to override reason, and succumb to ethnocentric nationalism. The genuine lover of life, Fromm wrote, “sees the whole rather than only the parts, structures rather than summations.” The lover of life “wants to mold and to influence by love, reason, by his example; not by force, by cutting things apart, by the bureaucratic manner of administering people as if they were things.” Participants in the peace movement refused to defer to bureaucratic mechanisms, accept widely publicized media half-truths, or anesthetize their elemental moral sensitivities to the catastrophe of war. They remained committed to nonviolent, rational, compassionate action.

That the rational and humane voices of so many ordinary citizens were marginalized—silenced, really—is no evidence of their impotence. Rather, this result evidences the failings of elected leaders and the structures of governmental institutions. The peace movement’s active expression of concern for their fellow human beings and courage to oppose their government’s lethal errors of judgment ought to be recognized as good in itself and worthy of both commemoration and emulation. Our ability to avert the next misguided, morally calamitous war may well hinge upon a proper appraisal of the meaning to be found in the historic peace movement that sought to stop the Iraq War.

If you enjoyed this post please share it with others and like it by clicking the heart icon. Be sure to subscribe if you haven’t already.

Invite Dr. Nall to Speak

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook or by leaving a comment.

This piece brought back so many memories! My wife and I we participated in the demonstrations in Rome - two of the 3 million !!