Why So Serious? Halloween, Popular Culture, and the Specter of Anonymous Authority

Part I of a series exploring what Halloween can teach us about dominant culture

Every Halloween, millions of children in the United States pour into the streets of nearby neighborhoods costumed as super-heroes, villains, monsters, murderers, fairies, princesses, soldiers, and the walking dead. Their motives are clear enough: locate neighborhoods with houses that give out the best candy. The hope is to return home with a hefty bag of sugary loot capable of paying the “parent tax” and leaving enough to satisfy their candy needs for weeks if not months to come.

But Halloween is about more than candy. The widely celebrated holiday offers us the unique opportunity to break with convention and unleash our imaginations. For a night, children and adults can be liberated from the strict confines of their pedestrian identities. We can costume ourselves as virtually anything, provided we can find our desired costume at a store or can afford the materials necessary to buy or construct the required ensemble.

For a night, a human can become an alien, vampire, or werewolf; the living can become the dead; children can become doctors, pilots, or astronauts; adults can become children; the weak can become strong; the fearful can become frightening; the meek can become bold. Halloween offers us the opportunity for instantaneous metamorphosis. Strangely, examining these fantastical and temporary transformations—aided by masks and swords, wands and wings—can reveal obscured insights about the power of culture and the personal identities beneath the costumes.

Halloween and Culture

Halloween is a $12 billion cultural event celebrated by a large majority of people in the United States. The 2023 National Retail Federation (NRF) survey of more than 8,000 people in the U.S. found that 73% expected to celebrate Halloween in one form or another. More than half planned to decorate their home or yard, 68% planned to hand out candy, and 50% intended to dress up in costume. Celebrants are projected to spend an average of $108 on each person’s costume. Consumers are expected to spend a total of more than $4.1 billion on adult, child, and pet costumes.

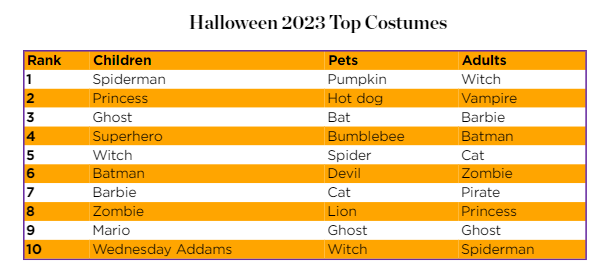

Ostensibly, Halloween offers ample opportunity for American individuality to manifest itself. Yet many children and adults opt to envision themselves as one of a handful of popular characters costumes. According to NRF’s 2023 survey, 2.6 million children are planning to dress as Spiderman and 2 million as their favorite princess. Another 1.5 million children planned to dress as their favorite superhero and another 1.4 million intended to dress as a witch. Batman, Barbie, Mario, and Wednesday Addams were also among the top ten costume choices for children. While Batman has been a mainstay costume for years, the popularity of the last three costumes is undoubtedly tied to popular media including the 2022 Netflix TV series, Wednesday, and the 2023 movies, The Super Mario Bros. Movie and Barbie.

Batman, Barbie, and Spiderman were also top-ten choices among adults. Nearly six-million intended to ride a broom into Halloween dressed as a witch. Another 2.4 million planned to blood-suck through the night as a vampire, while 1.3 million planned to don a cat costume. Taken together, more than 3 million expected to dress as either Barbie (1.4 million) or Batman (1.8 million).

Though Halloween offers children and adults expansive cultural permission to unleash their creativity and wear just about anything they want, most choose store-bought costumes. According to the NRF’s survey, consumers top sources for costumes are discount stores followed by costume stores. Just 13% intended to turn to crafts or fabric stores for their costume, and 12% planned to shop at a thrift store.

Obviously no one makes us wear one costume over another, unless we find ourselves at the mercy of an opinionated parent or partner. Most of us wear the costumes we choose. But these choices are not made in a social or cultural vacuum. As the philosopher Sally Haslanger explained, “Human beings are social beings in the sense that we are deeply responsive to our social context and become the physical and psychological beings we become through interaction with others.” We shape our personal identities in accordance with the cultural beliefs we adopt, from concepts about masculinity and femininity, to distinctions between beauty and ugliness, strength and weakness, success and failure.

Everyone is aware of the influence political decisions and laws exert over our lives. The influence of popular culture is comparably subtle, leaving many to overlook it as a source of insight into the character and structure of society and its members. Many view movies, music, and holiday rituals like dressing up for Halloween as frivolous leisure. Students of the humanities think differently. We understand popular culture as a “valuable index to what people commonly know, value, fear, remember, and believe,” as media studies scholar Jane Caputi put it. Culture is, after all, that human-made living repository of belief, feeling, values, hopes, dreams, inventions, and customs.

Too many think that studying culture is primarily studying other people’s culture—the “exotic” habits and beliefs of “foreigners.” But this is only a partial picture of cultural studies. Analyzing our own culture, particularly those parts of it we take most for granted, often yields surprising insights. The problem of course is that “our” cultural beliefs and practices just feel “normal,” the “way things are.”

The arts and humanities help us see the seams of our own culturally constructed reality. Take Nathan W. Pyle's “Strange Planet” comic in which the cartoonist depicts curious blue aliens examining the ways of life of earthlings. They attempt to understand our baffling beliefs and practices, describing suntans as “star damage,” for example. As outsiders to our ways, the aliens cut past the cultural veneer encasing our habits to describe them with comedic directness. A candle is “a primitive light source” that requires “a second tool to turn it on.” And though it may smell like food, “it’s not.” When it comes to Halloween, the aliens understand the trick-or-treat ritual as issuing an ultimatum: “Provide a sweet or face mild harassment.”

Pyle’s entertaining depictions give us fresh and illuminating perspective on the holidays, social interactions, and beliefs we presume to know so well. They help us more fully appreciate and also scrutinize the human-made parts of our world. We may even gain a deepened awareness that we are more than cultural consumers but also collaborators, however unconscious, in manufacturing culture.

As will become clear in this series, critically examining the mass-marketed Halloween costumes that we don each year illuminates important aspects of dominant culture. We can also learn something significant about our personal and social identities.

Who’s Really in Charge? Anonymous Authority

We quickly learn a deeper appreciation for the humanities and cultural studies when we begin to realize just how much of our lives is shaped by culture; from our self-conception, our expectations of others and society, to our notion of what is important or valuable. Culture, as has been pointed out by many, is to humans what water is to fish. It’s so much a part of our lives that it blends into the background of life, becoming paint on a familiar wall.

Though culture can often go unnoticed, it nevertheless shapes how we think of ourselves and our world. Culture conditions what Erich Fromm called our “social character.” In The Sane Society (1955), Fromm wrote that our social character functions to

“shape the energies of the members of society in such a way that their behavior is not a matter of conscious decision as to whether or not to follow the social pattern, but one of wanting to act as they have to act and at the same time finding gratification in acting according to the requirements of the culture. In other words, it is the social character’s function to mold and channel human energy within a given society for the purpose of the continued functioning of this society.”

Though we tend to envision ourselves as free in the absence of physical or legal constraints, philosophers, spiritual leaders, and psychologists have long shown that we are profoundly shaped and, at times, manipulated by unseen social-cultural forces. We undermine our autonomy when we uncritically adopt ideas, values, and habits that advance the interests of culturally dominant groups, even as those beliefs and practices undermine our own interests and potentialities. Overt, coercive control is no longer needed, and we become our own jailers.

The ironic state of our social character is that the more presumptive we are about our autonomy the more likely we are unwitting conformists. The explanation for this state of affairs was insightfully articulated by Socrates who explained, in Plato’s Apology, that wisdom grew in proportion to self-awareness of our limits.

When contemplating why the Oracle at Delphi determined he was the wisest man of Athens, Socrates realized that his wisdom was born of intellectual humility. After interrogating a man of high intellectual repute, in hopes of showing that the proclamation of his own wisdom was overstated, Socrates realized,

“‘I am wiser than this man; it is likely that neither of us knows anything worthwhile, but he thinks he knows something when he does not, whereas when I do not know, neither do I think I know; so I am likely to be wiser than he to this small extent, that I do not think I know what I do not know’” (21d).

The cognitive bias today described as the Dunning-Kruger effect conveys this ancient point well. Many exaggerate their capabilities or understanding in precisely those areas they have the least competency or knowledge. By contrast, the more we learn of the complexities of a given subject and discover the gaps in our knowledge, the less presumptive and excessively confident we tend to be.

Those most oblivious of the power of cultural influences are often the most successfully molded to the needs and interests of those with the greatest cultural power. In his 1941 examination of human freedom and fascism, Escape From Freedom, Fromm argued people living in non-authoritarian societies were given the illusion of being free, since they had been freed “of the older forms of authority.” Previously, power operated in a direct, overt, and coercive manner. But individuals in democratic societies were not as liberated as they imagined. Fromm contended that they had become “the prey of a new kind of authority,” what he called “anonymous authority.”

Anonymous authority does not directly and didactically present itself, and it is not physically coercive. Yet it potently shapes our thoughts, desires, identities, and choices through carefully devised marketing mechanisms and social norms. Anonymous authority combines direct consumer marketing with disproportionate influence in the wider popular culture and creative influence over our collective “common sense.” As Fromm explains,

“Anonymous authority is more effective than overt authority, since one never suspects that there is any order which one is expected to follow.”

The result is that we are guided to predetermined conclusions by external forces, but are left with the illusion of authentic, spontaneous decision making. “Most people are convinced that as long as they are not overtly forced to do something by an outside power, their decisions are theirs, and that if they want something, it is they who want it,” wrote Fromm. “But this is one of the great illusions we have about ourselves.”

Drawing on the Dutch philosopher Spinoza’s early insights into human conceptions of agency and freedom, Fromm contends that genuine human agency requires more than acting on desires but also having some meaningful influence over those desires.

“A great number of our decisions are not really our own but are suggested to us from the outside; we have succeeded in persuading ourselves that it is we who made the decision, whereas we have actually conformed with expectations of others, driven by the fear of isolation and by more direct threats to our life, freedom, and comfort.”

Fromm’s critique is not easy to entertain. The idea that our own thoughts, desires, and decisions—like our decision to be Batman or Barbie, pilot or flight attendant, cockroach or butterfly, kick-ass soldier or sexy soldier—are not authentically our own is not only strange; the suggestion also seems insulting as well as presumptive. How could it be that we do not know what we feel or prefer?

And yet our own experiences validate this challenge. How many of us have thought we wanted something only to realize we did not? How many of us have attempted to satisfy what we perceived as a burning desire only to realize the desire was not worth satisfying, or that in satisfying the desire we made ourselves less happy with the implication being that the desire may not have been authentically our own?

Anyone who has battled compulsive behavior—be it with food, drugs, or other unhealthy behaviors—can readily attest to the fact acting on what we identify, in one moment, as our immediate desires isn’t always in our own interest. Others of us have made choices—from staying up past our own designated bedtime, drinking too much, eating too much, or maintaining an unhealthy relationship—that were every bit as unwise as they were prompted by our desires. Part of personal development, as we all know, involves learning not only to act on our desires, but also to critically interrogate them and the motivating beliefs and assumptions at their root. When we do, we often discover conflicting desires. And some of our desires feel more authentically like our own while others feel imposed or strangely incongruent with who we are or wish to be.

Once we come to terms with the reality of being shaped by social-cultural forces, and that much of what we take to be “our own” is the result of socialization and acculturation, we are positioned to take the reins of our lives and begin to exemplify the “self-reliance” Ralph Waldo Emerson referred to in his 1841 essay. Contrary to popular belief, Emerson’s notion of self-reliance was not focused on financial independence but rather “non-conformist” character.

“Nothing is at last sacred but the integrity of your own mind. Absolve you to yourself, and you shall have the suffrage of the world….

“I am ashamed to think how easily we capitulate to badges and names, to large societies and dead institutions.”

The true aim of self-reliance according to Emerson, in sum, was intellectual independence and authenticity.

The feminist poet, Adrienne Rich, had much the same idea in mind, minus Emerson’s male-centered conception of intellect, when she gave her 1977 convocation speech, “Claiming an Education” at Douglass college. Rich urged the women at the college to reject educational models of passivity and recognize the value of claiming their education. Doing so meant taking responsibility to do their own “thinking, talking, and naming” in a male dominated world that had made these activities the prerogative of men. Such intellectual independence guides us to recognize the power uncritically absorbed cultural norms and values hold in directing our lives, often against our own interests and wellbeing.

The question remains how exactly social-cultural ideology shapes otherwise ordinary Halloween activities. On the surface, Halloween is a most whimsical and unserious of holidays. Candy, pumpkins, faux fall decor,1 fantastical costumes, and ritualized chicanery. (“Provide a sweet or face mild harassment,” as our blue alien friends put it.) For some, there is very little to think about. It’s just a good time.

Those of us in the humanities and cultural studies have learned to look beneath the outward masks of cultural practices. There we find intriguing, even profound questions about ourselves, others, and the wider character or even structure of society. The forthcoming parts of this series will specifically consider what mainstream, mass-marketed Halloween costumes can we learn about sex, gender, power in society. Though the journey threatens us with unsettling truths, it also offers the sweet reward of self-discovery.

Read part II: “Costumed in Gender, Haunted by Patriarchy”

If you enjoyed this post please share it with others and like it by clicking the heart icon. Be sure to subscribe if you haven’t already.

Invite Dr. Nall to Speak

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook or by leaving a comment.

Those of us in places like south and central Florida vigorously defend our right to “buy” our fall foliage. This is, after all, the only way we get seasons.

These are all really interesting insights about the nature of how culture impacts us but I think there’s an aspect of it that rarely gets explored.

The phrase “Think for yourself” is inherently contradictory. By definition, if someone else tells you to think for yourself, you’re doing what other people think you should do.

As a result, it reinforces the very thing it’s trying to get you not to do. You can also create a culture of belief in anti-establishment or “rejecting dominant structures” can become a dominant culture in and of itself. Which creates the problem where you end up realizing this and destroy your own ideas.

I think this is in part what we’re seeing. Halloween is intended to be subversive by dressing up as the thing you’re not so you can go back to your normal life refreshed. At least that’s my view.

The massive pressure to conform to grouping is so weighty. Especially for young people. I recall feeling myself to be agonizingly an outsider in high school. I'm still an outsider at 82 but cherish the freedom to build my own thoughts and personality. You brought up an important perspective, Dr. Nall.