A Brutal Invasion: Hidden Values and Two 20-Year Anniversaries

Part III of Media Omissions on the 20th Anniversary of the Iraq War

The decision to present facts about the dead without relevant context, such as whose choices generated those deaths, is informed by an unstated ethical premise. The author or institution has decided what is important or unimportant—or perhaps about who is important and unimportant.

The same media organizations offering decontextualized accounts of “lost” Iraqi lives report on the civilian casualties of the September 11, 2001 terror attack with greater clarity and relevance to reality. Specifically, they use language that accurately attributes agency to those directly responsible for causing the deaths of nearly 3,000 people in the Twin Towers and Pentagon attacks.

Consider ABC News’ coverage of the 20th anniversary of the attack: “On 20th anniversary of 9/11, questions, anger and death linger.” The headline itself rightly emphasizes the death generated by the attack. None of the previously mentioned articles on the 20th anniversary of the Iraq War use the word “death” in the headline. The differences between the news media’s coverage of the 20th anniversary of September 11, 2001 and the Iraq War go beyond headlines. In the ABC News piece we read,

“Saturday marks the 20th anniversary of the most lethal attack in history on American soil, a commemoration of the 2,977 people killed when 19 terrorists from half a world away hijacked and turned four commercial aircraft into missiles that rained death on New York City, the Pentagon and a field in rural Shanksville, Pennsylvania.”

There are many differences between the way the victims of September 11 are referred to such reporting in contrast to the victims of the Iraq War. The perpetrators of the attack are “terrorists.” For most people, the term terrorist carries an explicitly negative moral judgment. It is not a judgment-free factual description. Few participating in a military action would self-describe as a “terrorist.” Emphasis is also placed on how far the perpetrators had to travel to conduct their killings. Absent from the report is any detailed elaboration on the political rationalizations given by the perpetrators of the deaths. We read nothing of Osama Bin Laden's 2002 “Letter to America” in which he attempts—and fails —to justify attacks against the United States on the basis of our foreign policy decision making, and condemns our cultural tolerance of "homosexuality," "gambling," sex industries, and drug sales and use. Indeed, few media outlets have ever referenced specific details from the text, an obvious value judgment in terms of what is epistemologically or ethically relevant for readers to read.1

Perhaps the difference between the innocents killed during September 11 and those killed in the invasion of Iraq has to do with motive. Some will argue our nation’s motives were high-minded, while the terrorists were not. But should such a judgment be made for the reading public by authors of the news? We are again reminded that even our selection of facts entail judgment.

Also notice that we do not read “a commemoration of the 2,977 people the United States lost…” Such a statement, unless it was earlier contextualized with information about those responsible for the deaths, would not be more objective for being more detached. Quite the opposite, we would think we are learning about the arctic fox from someone who does not know the first thing about the arctic nor foxes. Rather it would lack vital information to help us grapple with the human reality of the attacks.

The ABC News piece correctly identifies the 911 dead as “victims.” The term “victims” also entails a judgment about someone’s innocence or the wrongfulness of their treatment. To be clear, I do not object to the use of any of these terms or characterizations in this context. Yet use of such language in this context belies the claim that reporting must never make “judgments” for the reader and that reporting can and should be “value neutral.”

The second, larger point is that our news media fails to extend the same humanizing language to the victims of the U.S. invasion of Iraq. Not one of the previously mentioned news articles on the 20th anniversary of the Iraq War refer to civilians killed by the United States and its Coalition as “victims.” Yet basic reasoning makes it clear that the children and non-combatant adults killed during the U.S. bombardment of Baghdad were no less deserving of life and no more deserving of death than those killed on September 11. The failure to extend the same humanity to those that we extend to innocents killed in our own country is a violation of the basic premise of impartiality and the ethical principle enshrined in the Declaration of Independence, recognizing that all are equal in moral worth.

The aim of objective reporting should not be “value free” but genuinely objective and ethically consistent reporting in pursuit of truth. Here it is apt for us to hear, once more, the wise words of humanistic psychologist, Abraham Maslow. In Religions, Values, and Peak-Experiences (1964), he wrote

“Any philosophy that permits facts to become amoral, totally separated from values, makes possible in theory at least the Nazi physician ‘experimenting’ in the concentration camps, or the spectacle of captured German engineers working devotedly for whichever side happened to capture them.”

Philosopher Val Plumwood extended this line of thought in Environmental Culture: The Ecological Crisis of Reason (2002). She argued that there are instances in which the absence of ethical and emotional consideration constituted irrational and condemnable thinking.

“emotional neutrality or the absence of emotion in certain contexts (most obviously that of harmful experimentation) is not an admirable trait but an indication of a deep moral failing. Disengagement and neutrality are as mythological in science as in the market, but the insistence on these ideals creates a commitment vacuum in science, reduces the ability to resist cooption by economic forces, and works systematically against a science committed to socially responsibility.”

The aim in juxtaposing the 20th anniversary of coverage of the September 11 attack with that of the Iraq War is not to suggest ethically numb, innocuous language ought to be more routinely used to describe innocent human beings destroyed in politically motivated attacks. The claim is that we ought to question why the culturally dominant manner of reporting on the victims of our government and military actions are not treated with equal humanity. A nation that wields such lethal force has an obligation to critically reflect, with painfully opened eyes, upon its actions.

A Brutal Invasion: The President and a Soldier

Twenty years after the invasion of Iraq there is no question that Saddam Hussein did not have weapons of mass destruction. Former Senator Hillary Clinton, for one, admitted her vote to authorize the use of force was a mistake. Biden, now president, has given alternating perspectives on the war he helped build the case for.

Not everyone has regrets. Former president George Bush has said he does not regret invading Iraq, even though he admits claims of Iraq having WMDs was wrong. Former vice president Dick Cheney rejected any notion invading Iraq was a mistake. Similarly, Condoleezza Rice, who was National Security Advisor in 2003, defended going to war in a 2011 interview with Piers Morgan.

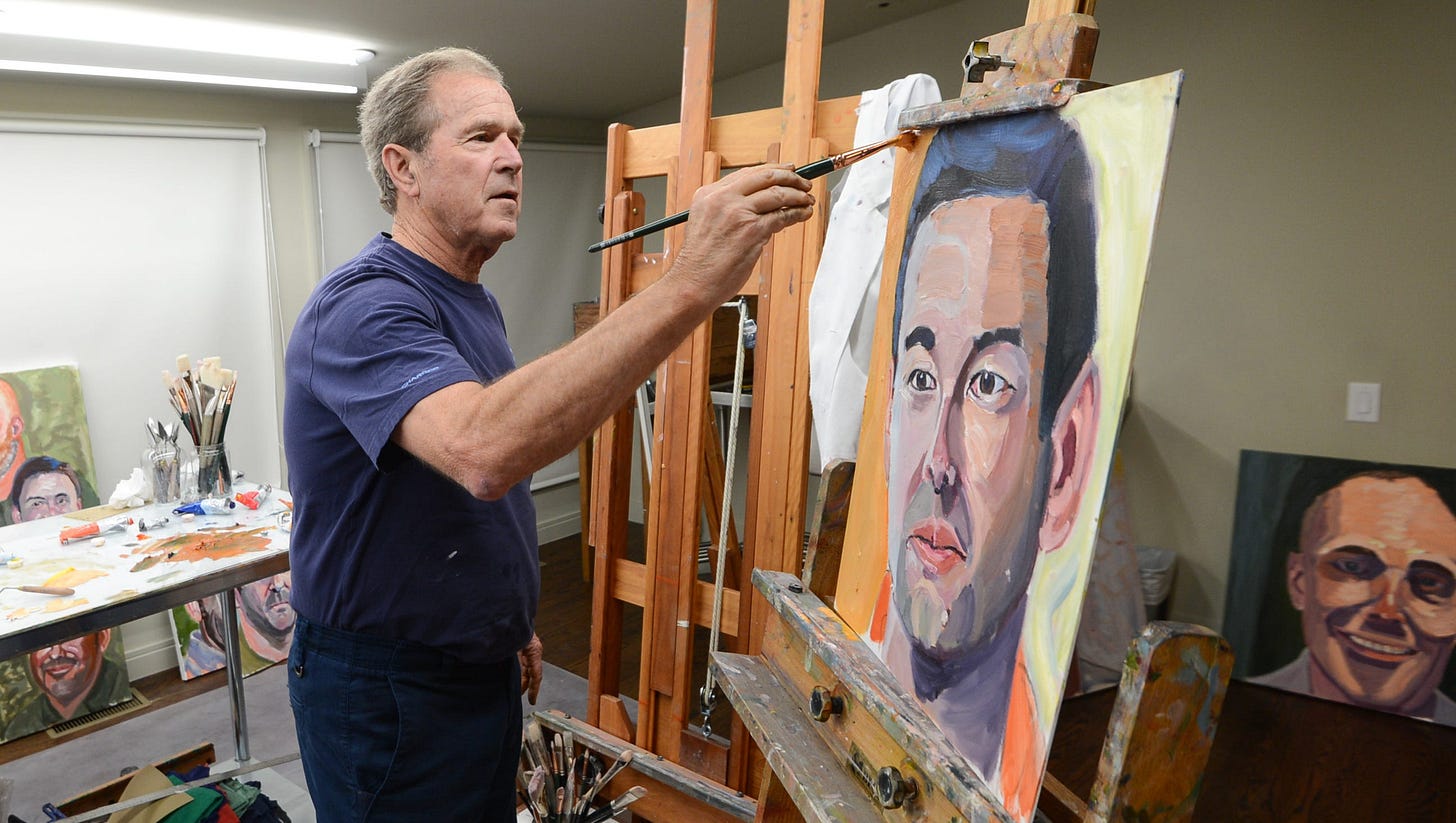

In recent years, Bush has turned to artistic expression. In 2017 he published, Portraits of Courage A Commander in Chief's Tribute to America's Warriors.

University of Virginia historian, Melvyn P. Leffler, author of Confronting Saddam Hussein, conjectured that Bush’s paintings might suggest a sense of “agony, of responsibility, of regret for those whose lives were scarred forever and for those who perished.” More recently Bush has turned his creative attention to nature. The New York Times reports that the former president is painting birds and flowers as of late. There’s been no word, just yet, on when or if he will get around to painting Iraqi civilians who survived the invasion he launched.

Though Bush was notably absent from public dialogue on the 20th anniversary of the Iraq War, he has not disappeared from the public stage. In fact, Bush and Rice have joined other supporters of the Iraq War to denounce Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But even Bush seemed unable to suppress awareness of the disturbing parallels between the invasion of Iraq and the invasion of Ukraine. During a May 2022 speech condemning Russian aggression Bush said,

“...the result [of anti-democratic repression] is an absence of checks and balances in Russia and the decision of one man to launch a wholly unjustified and brutal invasion of Iraq. [Brief pause.] I mean of Ukraine.”

We might read Bush’s faux pas as inadvertently acknowledgment that the invasion he launched was unjustified and brutal. It’s worth considering Leffler’s interpretation of Bush’s paintings of veterans in light of this slip of the tongue.

Most importantly, we might contemplate the strangeness that a head of state responsible for leading a nation to war for a reason proven false, a war with such destructive and lethal results, continues to be given such a grand platform upon which to speak about matters of war and peace, about other heads of state engaging in brutal and unjustified invasions. We might even ask why or how those responsible for endorsing such a catastrophic war remain in positions of power in our government and politics.

But those of us who believe in democratic discourse will not wish to see Bush disappeared from the wider dialogue. Rather, we will insist that his voice be part of wider conversation with others.

We will want to know, for example, how Bush’s accidental conflation of Iraq with Ukraine, and therefore himself and Putin, lands with the soldiers sent to eliminate WMDs in Iraq. We will want to know how the Iraqis who endured the invasion and subsequent occupation feel—yes, feel—about his remarks and also his art. We will also ask to see more art displayed alongside Bush’s. Art by U.S. soldiers. Art of and by Iraqi civilians, visions of healing and visions of accountability.

We will want to give voice to those experiences that are too often left out, as though they did not exist or did not deserve to exist. We will want to make space for Tomas Young, who was shot and paralyzed five days into his 2004 Iraq deployment, to be heard once more. Young was inspired to join the U.S. military following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. His journey from volunteer serviceman to paralyzed veteran and outspoken war critic was featured in the 2007 documentary, Body of War. He died at the age of 34 in 2014.

In a letter to Bush and Cheney, on the 10th anniversary of the Iraq War, Young wrote,

“…I hope, for your sakes, that you find the moral courage to face what you have done to me and to many, many others who deserved to live. I hope that before your time on earth ends, as mine is now ending, you will find the strength of character to stand before the American public and the world, and in particular the Iraqi people, and beg for forgiveness.”

Such a perspective is rarely openly aired in mainstream media, thus silencing the voices of some veterans. Young’s experience and view of the Iraq War and the U.S. leadership of the time does not reflect those of all veterans. But neither do veterans like U.S. Air Force Major Steve Ankerstar. Military veterans, like the broader population, hold varied, complex views on warfare and politics. The tragic irony is that the failure to more fully represent the array of soldiers’ military experiences functions to not only leave some veterans feeling isolated and silenced, it also manufactures a “common sense” ideology that thwarts the very critical thought and dialogue about when and where to go to war and whether or not we ought to continue to devote such a large share of our nation’s wealth and resources to industries of war.

As we leave twenty years behind and step toward a ten-year climb to the 30th anniversary of the Iraq War, let those of us truly committed to objectivity and the dignity of human beings demand our news media and political discourse offer a more honest, open, and wide-ranging rendering of the facts.

If you enjoyed this post please share it with others and like it by clicking the heart icon. Be sure to subscribe if you haven’t already.

Invite Dr. Nall to Speak

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook or by leaving a comment.

Thank you for bringing this common sense idea to the surface. It's not surprising that aggressors want to prettily their underlying plans so that citizens will buy in. I'm appaled at the whole idea of dragging a whole population into wars of no benefit to anyone but a war machine and a few misguided hawks.