Silly Girls, Muscles and Masks Are for Boys: How Halloween Costumes Model Patriarchal Stereotypes

Uncovering the overlooked features of common Halloween costumes subtly teaching children what it means to be a boy or girl.

A few years back I visited a do-it-yourself haunted trail in a nearby small town. Volunteer scare actors prowled the wooded trail. Wearing top-notch latex masks and blood-splattered jumpsuits, they revved up chainsaws, menacingly clanged on metal objects, and jumped-scared patrons when they could. The most frightening part of the experience was the most furtive of the trail’s terrors.

I walked with caution and vigilance, looking ahead for pretend threats. What I wasn’t expecting was a throaty scream at my ankles. A dedicated child scare actor who couldn’t have been more than eight or nine waited for her unsuspecting victims in the shadows on her hands and knees. As I approached, the child rapidly and imperceptibly moved before me on the dark dirt trail and let out a raspy scream through gnashed teeth. She was at my feet and I didn’t even know it! It was my unwariness, in that brief moment, that made the scare so frightening.

Our greatest scares often come from things closest to us and least suspected. It’s the seemingly innocent or most trusted parts of life that turn us into the most unsuspecting and therefore surprised victims. And it’s not just the ghoulish children of the forest we have to worry about on Halloween night. Those of us committed to the idea that men and women share not only an equal dignity but also an equal right to determine their identities may be disturbed to realize something as innocent as common costumes perpetuate patriarchal stereotypes.

A 2000 study of Halloween costumes published in Psychology of Women Quarterly found that most children's costumes conformed to conventional gender stereotypes. The study authors found

“feminine costumes were clustered in a narrow range depicting beauty queens, princesses, and other exemplars of traditional femininity and contained a higher proportion of costumes of animals and foodstuffs. Masculine costumes emphasized the warrior theme of masculinity and were more likely to feature villains, especially agents or symbols of death.”

The findings documented in part two of this series, “Costumed in Gender, Haunted by Patriarchy,” show that though girls do have more options, today, costume options for boys and girls remain narrowly constrained to dominant gender stereotypes. Costume names give us a good idea of these constraints. Girls can choose to be the “buccaneer beauty,” “cute cop,” or “charming wolf.” Boys get to be the “pirate pillager,” “police officer,” or “hungry howler.”

But patriarchal gender stereotypes aren't just revealed in the difference of costume names. These stereotypes are exemplified and perpetuated in the costumes’ designs and how they're modeled on the package. Together, costume names, design, and modeling show boys and girls how to be the right kind of pirate, police officer, or wolf.

I am genuinely interested in readers’ experiences dressing up for Halloween as children. What was your experience like? Did you ever choose a costume that ran counter to dominant cultural expectations? Were there repercussions? Did your parents require you to pick from the “boys” or “girls” section when you would’ve rather explore all sections? Were you ever discouraged from dressing up as a particular character or in a particular manner due to gendered expectations? Share your experience in the comment section.

Cute Girls and Active (or Even Violent) Boys

Costumes sold to boys promote the idea that their purpose is to look tough and be ready for a fight. Be they action-heroes, officers, athletes, monsters, or pirates, costumes marketed to boys feature models standing in postures conveying action, strength, assertiveness, and agency. Boys can be Spiderman, Batman, ninja, pirate, wild animal, or a monster; yet in each instance, they are not to be trifled with. They mean business and are ready to take action.

It's not just the postures of the models that convey assertive and often aggressive agency. Most masks accompanying boy costumes feature built-in expressions of anger, rage, or even madness. When the faces of the costume models on the packaging can be seen, they usually brandish stern eyes and sneers.

Beyond assertive stances and sneers, we can tell the costumes marketed to boys are meant to command respect if not fear by the absence of frills and the presence of, well, pants. In contrast to most action-hero costumes marketed to girls, usually featuring a tutu and smiling model on the package, the action-hero costumes marketed to boys communicate the message, “I am here to directly impact the world,” namely through force. Being attractive or pleasing is not important.

Costumes marketed to girls convey the principle that girls’ purpose is to look cute or beautiful. Models featured on costume packages convey passivity, receptivity, whimsy, and/or playfulness. Whereas some boy costume models smile, most girl costume models smile. A smiling face on costumes marketed to girls is as common as a staid or fierce facial or mask expression is the norm for boys’ costumes. This is true whether she is a princess or witch, fairy or bat, angel or devil, nurse, or superhero. The modeling for Party City’s hooded cape exemplifies this norm:

Those modeling costumes for girls bare their teeth for smiling whereas the models on the costumes for boys often bare their teeth to represent anger or viciousness. Even when neither is smiling, only the boys are permitted to scowl. The most menacing expression allotted to girls within this patriarchal framing is displeasure.

Girls Don’t Get Muscles. But Boy Babies Do.

Muscles are yet another means by which patriarchal definitions of femininity and masculinity are communicated through Halloween costumes. One reason gender is such a powerful force in our lives is because it appears to be based on biological reality. The symbolic deployment of muscles in Halloween costumes exemplifies this pseudo-naturalism.

Muscles, popular costumes subtly teach us, belong exclusively to boys and men. This much is clear from the fact that mass-marketed girls’ costumes never feature the foam-padded muscles accompanying many boys’ costumes. Whether the costume is intended for a toddler or a teenager, the boys’ superhero costume often comes equipped with more muscle than most men could ever hope to develop. We see a clear example of this in the “Fireman Toddler Muscle Costume,” for sale at Target.com and Walmart.com in 2024, and Spirit’s toddler Batman costume.

Even some superhero costumes marketed to baby boys come equipped with muscles! This was the case for Target’s Batman baby costume, which featured graphic designs on the jumpsuit intended to make the baby look absolutely ripped.

Some will respond by arguing that the costumes simply reflect the appearance of the heroes and heroines they are designed after. And it is true that many of the most popular female superhero characters, including Shuri from Black Panther, Harley Quinn, Wonder Woman, Supergirl, and Captain Marvel, distinctly lack the kind of exaggerated muscularity of contemporary male superheroes.

Yet this rebuttal falls short at a second glance. Let’s set aside the fact that six-packs were not the norm among iconic superheroes of the 1950s, 60s, and 70s—Batman and Superman. Many of the costumes marketed to boys make unfaithful embellishments to the original character’s appearance. The many brawny muscle-padded Spiderman costumes, for example, do not reflect today’s cinematic Spiderman as portrayed by Tobey Maguire, Andrew Garfield, and Tom Holland. So why not embellish some of the girls’ costumes with muscle as well?

Better yet, given that superheroes are purely fantastical creations, as is made clear by the abnormally muscular bodies of contemporary male superheroes, we should ask the question, why aren’t more female superheroes given the muscles that so clearly symbolically represent heroic power within the dominant culture?

Those who say that this critique is a stretch because muscles on Batman make sense in a way muscles on Wonder Woman don’t need to answer this question: Why aren’t there muscles on the Superman, Batman, and Spiderman costumes marketed to girls?

Are we really to believe that the decision to add muscles to a baby Batman costume for boys makes sense in a way that adding padded muscles to a tween girl’s Batman costume doesn’t? The simple explanation for this apparent inconsistency is that patriarchal values define “power,” represented through muscularity, as distinctly and inherently masculine. Though many would have us believe Halloween is just a fun-filled flight into the fantastical, the truth is that the firm rules of patriarchy quietly govern even our imagination. Whatever share of power women are permitted must be smaller than that allotted to men. And that is the symbolic universe where most mass-produced Halloween costumes work.

Modeling Patriarchy

We can better understand the consistent symbolic beliefs at work during Halloween by turning to sociologist Erving Goffman’s analysis of advertisements. In his book, Gender Advertisements (1979), Goffman observed that advertisements portrayed women in radically distinct ways compared to men.

One reoccurring theme was what he called “ritualization of subordination” in which women enacted a number of body positions that symbolically communicated passivity and a lack of agency. These positions included the head cant, in which the head is tilted to the side, the bashful knee bend, in which she stands at whimsical ease or simply off-center, and the self-touch. Women, represented in this manner, are decorative rather than autonomous. In carefully analyzing advertisements, Goffman discovered that adult women were frequently infantilized, and portrayed as naive, shy, or coy. Men, by contrast, stood straight and square; hands at their sides, arms crossed, or fists on their hips.

Walking through a Halloween costume shop you will find costume models reproducing these same symbolic expressions of stereotyped femininity and masculinity. The models for costumes marketed to boys and men take firm stances, poised to act upon the world—to alter or mold it. By contrast, models for costumes marketed to girls and women are more likely to be standing off-kilter, with a knee bent inward, toes on opposite feet turned toward one another or legs crossed, a dipped shoulder, a hand on hip, and, as mentioned above, usually a smile.

The influence of these models shouldn’t be ignored. Children are social sponges. Wary about awkwardly standing out and being subjected to ridicule, they are adeptly attuned to what is “right” or “normal” among their peers. I was reminded of this during the Halloween of 2021 when one of my children, who was five at the time, brought the front package of his ninja costume to his mother to be used as a guide for his costume makeup. For many children, the costume model functions as an instruction manual for the wearing of the costume.

To be clear, I am not arguing that there’s something wrong with smiling or playfulness. Nor am I am I suggesting that dominance and power-over others is something that ought to be so celebrated in boys during Halloween. Authentic power, as that exemplar of humane and enlightened manhood, Erich Fromm, expressed it in Escape from Freedom (1941), is antithetical to power-as-dominance.

“The word power has a twofold meaning. One is the possession of power over somebody, the ability to dominate him; the other meaning is the possession of power to do something, to be able, to be potent. The latter meaning has nothing to do with domination; it expresses mastery in the sense of ability. If we speak of powerlessness we have this meaning in mind; we do not think of a person who is not able to dominate others, but of a person who is not able to do what he wants. Thus power can mean one of two things, domination or potency….”

For Fromm, resorting to domination evidences desperation and the inability to shape the world through uniquely human abilities. The dominating person is thus impotent in this respect.

Genuine and humane power is the development and use of reason, compassion, and creativity to affect the world. Those who dismiss such a vision of power or abandon desires for a healthier vision of masculinity rooted in love and non-violence do so in the face of great thinkers such as the Buddha. “Let a man overcome anger by love [or non-anger],” explained the Buddha, as documented in The Dhammapada, “let him overcome evil by good; let him overcome greed by liberality [generosity], the liar by truth!”

By recognizing the different costumes marketed to children depending on their gender identity, we are alerted to patriarchy’s deeply embedded and ongoing influence in shaping our ideas about who we are and who we can be. And those of us who value human autonomy and independence—freedom—will find such an ideology worth calling into question. We will also be in a better position to reimagine healthier and more humanistic visions of power.

A Tale of Two Boxers

Even when girl costume models portray boxers, they do it with a smile that conveys playfulness, not the ferocity and determination needed to knock out their opponent. Compare the “Everlast Boxer” costume marketed to girls to the one marketed to boys. Both come with shorts, hooded robes, and gloves. But those are just the straightforward jabs. It’s the surprise hooks we have to look out for.

We aren’t surprised to see that the girl’s costume is pink while the boy’s is pink. Few recognize that this patriarchal gender color scheme was inverted 100 years ago. During the first 30 years of the 20th century, pink was marketed as a color for boys since it was closer to red, symbolic of power and, as per patriarchy, men. Blue, on the other hand, was thought to reflect something that is delicate, and thus girls and women.

Beyond color, we see that the boy’s shorts are designed to hang below the knee. The girl’s shorts are significantly shorter, stopping around the thigh. The second difference is that the boy’s costume features a muscle vest. Characteristically, the girl’s costume does not come with built-in muscles.

The other major differences have to do with the modeling of the costume and accompanying makeup. The postures of the product models are not organic. They are directed by adults. The boy model takes a standard power stance expected of a boxer. His legs are spread out to hold his ground in anticipation of a blow by his opponent. His facial expression is appropriately stern given that he is readying himself for violent combat. To land the punch of the costume, makeup is added to the boy in blue’s right eye to represent a black eye. He’s not playing around, or so he aims to convince us. He’s a “born” fighter. We find a very similarly designed costume marketed to very young boys, too.

The modeling of the girl’s costume is very different. Her legs are close together. She flashes a wide, friendly, teethy smile. This is no fighter. She’s just a child loosely pretending to be a boxer, a boxer who’d just as soon hug you than hit you. Taken together, these two costumes reinforce the idea that the basis of feminine worth is in pleasantness and cuteness, and the value of masculine worth is in the capacity to enact force—to do violence.

The significance these costumes have on our imagination becomes clearer when we realize how easy it is to think of a man or male boxer exerting physical force over another person’s body. Consider how far off the above boxer costume marketed to girls is from the attire and demeanor of the American female boxer, Claressa Shields.

Shields won a gold medal in 2012, the first year women’s boxing was included in the Olympics. She won gold again in the following Olympics, in 2016. Shields is among an elite group of boxers to hold all four major world titles in boxing. Why not model a girls’ boxing costume on one of the greatest living female boxers?

To be clear, I’m not advocating for more children to embrace the boxer persona. A society that truly objects to violence must ask serious questions about the wisdom of inviting people, especially males who are responsible for the overwhelming majority of violence in society, to see themselves as fighters. What are the consequences of promoting a violent self-image to boys who will grow up to be men? How might their self-image and capacity to engage in non-violent communication be improved if they could adopt the relaxed, playful demeanor of the girl costume model?

Radical feminist critics of patriarchal gender including bell hooks, Robert Jensen, and others, do not think the solution to sexism is to have girls adopt the self-identity of a violent, conflict-oriented masculinity. Better to identify the best qualities in the dominant visions of masculinity and femininity, add the missing humane and humanistic characteristics, many of which are conceived of as inherently “feminine,” and remake our notions of the social-cultural meaning of manhood and womanhood.

Silly Girls, Masks Are for Boys. Now Show Us Your Teeth

One of the most overlooked differences between costume designs for boys and girls is also one of the most important in recognizing the influence of patriarchal ideology. It’s a difference literally staring us in the face.

Very few girl costumes feature mouth and face-covering masks. In my 2024 examination of Halloween costumes, I found that 16 of the 40 superhero costumes on Party City’s website featured face and mouth-covering masks. Zero of the 22 superhero costumes offered to girls included such masks. Of the 60 “scary” costumes offered to boys via Party City’s website, 50 included face and mouth-covering masks. Zero of the 38 “scary” costumes offered to girls featured such masks. One of the girls’ costumes included a mask covering the mouth only.

Similar patterns were observed in adult costumes marketed to men and women. Of the 77 “scary” costumes in the men's section at Spirit Halloween, 49 featured face and mouth-covering masks. Only one “scary” costume in the women's section at Spirit featured a face and mouth-covering mask: “Adult Lady Liberty Costume - The Purge.”

As previously demonstrated, costume options for girls and women have expanded to include “feminized” versions of male characters. Today, girls can dress as one of the Mario Brothers, Jason Voorhees from Friday the 13th, Spiderman, one of the four Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, or some other character in the growing selection of beloved male protagonists marketed to girls.

Though this shift suggests an undermining of sexist attitudes toward women, a closer analysis reveals the ongoing influence of androcentrism or male-centeredness in the dominant culture. In the first place, the “femininized” versions of the costumes symbolically reinforce the idea that beauty is the essence of womanhood.

Equally important, the gender-bending costuming doesn’t go both ways. While girls and women are increasingly invited to dress up and therefore identify with male characters, boys and men are not given a similar offering of female characters to dress up as or identify with. In other words, girls get to dress up as Sonic the Hedgehog or Jack Skellington from Nightmare Before Christmas, but boys are not invited to dress up and therefore identify with Amy Rose or Jack’s counterpart, Sally. Neither are boys given the opportunity to identify with female heroines such as Captain Marvel, Black Widow, Wonder Woman, Gamora, Jean Grey, Storm, or Mystique. The only exceptions to this rule are gag costumes intended to be worn as an intentional joke.

Girls’ costumes often lack mouth and face-covering masks even when the character being emulated wears or would require one. One example includes a Pokémon costume of Pikachu marketed to girls. Compare the one for “her” to the one for “him.”

Similarly, the only version of the character Sam, from “Trick r’ Treat,” marketed to girls is maskless as well as characteristically “feminized.”

I challenge readers to observe Halloween costume selections in stores or online to find more than a very limited selection of costumes intentionally marketed to girls or adult women with masks that cover their entire faces.

In some cases, even when a mask is included in the package, the model on the package does not wear the mask. Take the costume for the Avenger “Rescue” marketed to girls. The Rescue costume comes with the relevant jumpsuit, sans muscle padding of course. It also includes the relevant mask. But the model holds the mask rather than wearing it. No one will be surprised to learn that the models for similar costumes marketed to boys such as Iron Man do not hold but actually wear the mask.

Usually, costumes emulating characters with masks feature alterations when they are marketed to girls. Take a look at the costume for the Marvel superhero the Wasp. Compare the costume, which is available at many stores, with the actual superhero’s depiction. What’s the difference? And what does that difference allow for?

For those who don’t know, the Wasp is a female character allied with Ant-Man. With this in mind, compare the Wasp’s costume to the Ant-Man costume marketed to boys.

The obvious difference is that the Wasp’s mask has been altered to show the model’s mouth, more of their cheeks, and, not unimportantly, their long hair. Ant-Man’s mask attempts to faithfully reproduce the original. So why is the costume of the heroine altered while Ant-Man’s approximates the original?1 It’s worth mentioning that the adult Wasp costume has the same modifications.

Less someone insists this is an exception rather than a (patriarchal) rule, I offer Spider-Gwen as another example of a rule that she shall not hide her smile. Target’s “Marvel Ghost-Spider Gwen” costume comes with a mask, but not one that matches the actual character.2 The significance of omitting the mouth-covering from the mask is made clear by the visible smile of the costume model.

Similar adaptations are made for women’s Pink Power Ranger costumes. The “Pink Ranger Sassy Bodysuit” costume and Target’s offering of the same costume replaces the actual character’s helmet with what are basically sunglasses with a pink strip running along the top rim of the glasses. The model for each costume wears heels, though they are apparently sold separately.

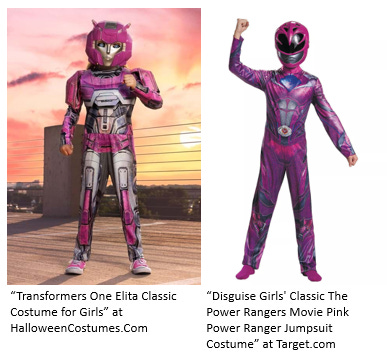

The example of the Transformers One Elita costume for girls and the Pink Ranger Costume show below are remarkable for their break with the previously discussed patterns. They also remind us that none of these social norms are set in stone or necessitated by non-social-cultural factors.

Of the 116 superhero costumes marketed to girls through HalloweenCostumes.com, during the 2023 season, only eight were equipped with full face-covering masks. Four were costumes based on male characters that also appeared in the boy’s section and were simply cross-listed in the girls’ section. By contrast 72 of the 221 superhero costumes offered to boys featured masks that covered the entire face. What gives? I can anecdotally attest to the reality that boy children are no less averse to wearing a face-covering mask while trick-or-treating than girls.

Even when a hero costume marketed to girls comes with a partial mask, models sometimes hold rather than wear the mask. This was the case for Target’s “Rubie's Girls' Justice League Batman” costume. She holds the masks, and flashes a pleasant smile, while her right leg is bent inward, what Gerbner called the “bashful knee-bend.” This isn’t a superhero prepared for battle.

As previously discussed, mass-marketed costumes adapted for women based on villainous men of classic horror films usually omit the mask. This is significant given that the mask, when part of the male costume, is probably the most important component. The masks of Jason Voorhees, Michael Myers, and Leatherface are vital components of their iconic identities. Similarly, Freddy Krueger’s scared face is fundamental to his backstory.

It could be argued that patriarchal masculinity is itself a mask concealing men’s humanity and enabling them to carry out the otherwise unconscionable violence that has so long been tasked to men on behalf of those with the greatest political-economic-material control in society. The point here is that the masks and disfigured faces of these masculine anti-heroes of horror are elemental to their characters. Yet they are glaringly absent from costumes marketed to women. And when the masks are included, as noted above, they are often held in hand and not worn by the models.

The face is a central site for the performance of properly patriarchal feminine and masculine selfhood. Bashful eyes and sweet smiles communicate the essence of patriarchy’s conceptualization of femininity: compromising, soft, pretty, and compliant. By contrast, most boys’ and men’s masked costumes symbolize menace, dominance, violence, or (plastic) stoicism.

By critically examining Halloween costumes, we penetrate the surface level of cultural belief and behavior. There we discover a deeper layer of costume hidden beneath the external guise of the pirate, fairy, murderous clown, or superhero. As feminist historian Gerda Lerner put it in The Creation of Patriarchy, patriarchal gender is “a costume, a mask, a straightjacket in which men and women dance their unequal dance.” Ironically, it may be Halloween, of all holidays, that offers us the best opportunity to see beneath the mask of patriarchal ideology and liberate ourselves of its dehumanizing veneer.

Read the first three parts of this series examining culturally hegemonic gendered expression in Halloween costuming:

If you enjoyed this post please share it with others and like it by clicking the heart icon. Be sure to subscribe if you haven’t already.

Invite Dr. Nall to Speak

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook or by leaving a comment.

One objection here may be that there are, increasingly, more costumes marketed to boys with partial masks that do not cover the mouth. This trend makes sense to me. My children have rarely kept their masks on for much of the trick-or-treating night. It’s hot. Especially here in Florida. Still this objection falls short. While boys are increasingly offered partial masks of their favorite superhero, there remain multiple full-face covering mask options in the designated “boys” sections. Girls are not offered an equal range of options.

I've noticed this too. What a creepy throw back!

I actually did a Halloween party in drag in about 7th grade circa 1964ish. It may have been a time while drag was somewhat acceptable due to characters as Milton Berle and movies like “Some like it Hot” with Jack Lemon and Tony Curtis. Reception as I recall was mixed but I did win best costume a box of chocolate cherries the prize.

It seems the wave of conservatism of Reagan really set the “gender norms” in concrete for years. My kingdom for a return to the 60’s and 70’s when things were fun.