Taking Games Seriously: Pankration, the Olympics, and Our Sports Imagination

What we can learn from thinking about an ancient sport missing from the modern Olympics

The 2024 Summer Olympics consisted of 32 sports including everything from aquatics and archery to boxing and golf. That's significantly more variety than the first Olympics of 776 BCE, which featured just one type of competition. At its peak, the ancient festival honoring Zeus never included more than six kinds of contests. Still, the ancient Olympics featured one sport that our contemporary Games do not: pankration.

Recognizing the absence of this brutal combat sport, much beloved by the ancients, prompts us to reflect on the rich history of human athletics and it's implications for us, today. Examining the ancient Olympics also helps us contemplate overlooked questions about the meanings within our sports and the influence they have in our personal and political lives.

The first thirteen Olympic competitions, each held at the sanctuary of Zeus in Olympia, Greece, featured just one sport: a sprint called the stadion. A stadion was a unit of measurement representing 600 feet in ancient Greek terms, believed to be about 150 to 200 meters. Stadion was also the name for the place where the competitions were held. The continued influence of the ancient Greeks and Romans is indicated by the name we give to places where athletic competitions are held: “stadium,” after the Latin version of stadion.

Even at its most diverse development, the ancient Olympics featured few of the events we’ve come to expect in the contemporary Games. Longer distance footraces were the first new additions, made in 724 and 720 BCE. By the middle of the 7th century BCE a total of six categories of competition were added including equestrian events, boxing, wrestling, and the pentathlon which combined the long jump, javelin and discus throwing, stadion, and wrestling.

Such was the athletic offering of the Olympics for nearly eleven centuries of continuous competition. During this time the Greeks held some 293 quadrennial competitions.1 The 5th century BCE Theban poet, Pindar, credited none other than Heracles—Hercules, in ancient Rome—with having created the Olympics. In his tenth Olympic Ode Pindar wrote that Heracles celebrated victory over an enemy by creating a sacred grove at Olympus in honor of his father, Zeus, and his fellow Olympian gods, and initiated “the four years' festival with the first Olympic games and its victories.” Though the Olympics came to an end around the 4th century CE, they were revived some 1,500 years later, in 1896. And though the contemporary Olympics feature footraces, boxing, wrestling, equestrian events, and all components of the ancient pentathlon, there’s one sport that we have never seen in the modern Olympics: pankration.

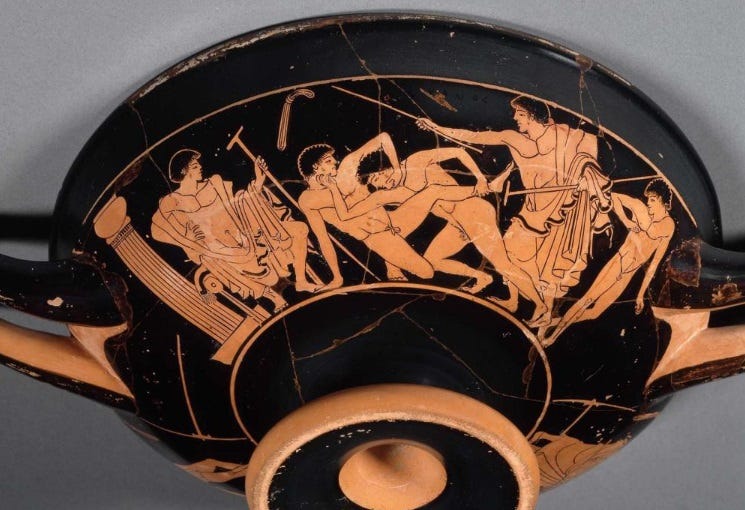

The ancient combat sport combined boxing and wrestling, and was first played at the Olympics in 648 BCE. It was the third combat sport added to the Olympics following the addition of wrestling in 708 BCE and boxing in 688 BCE. By 200 BCE a youth pankration competition was added allowing non-adult males to fight one another in the truly “no holds barred” competition.

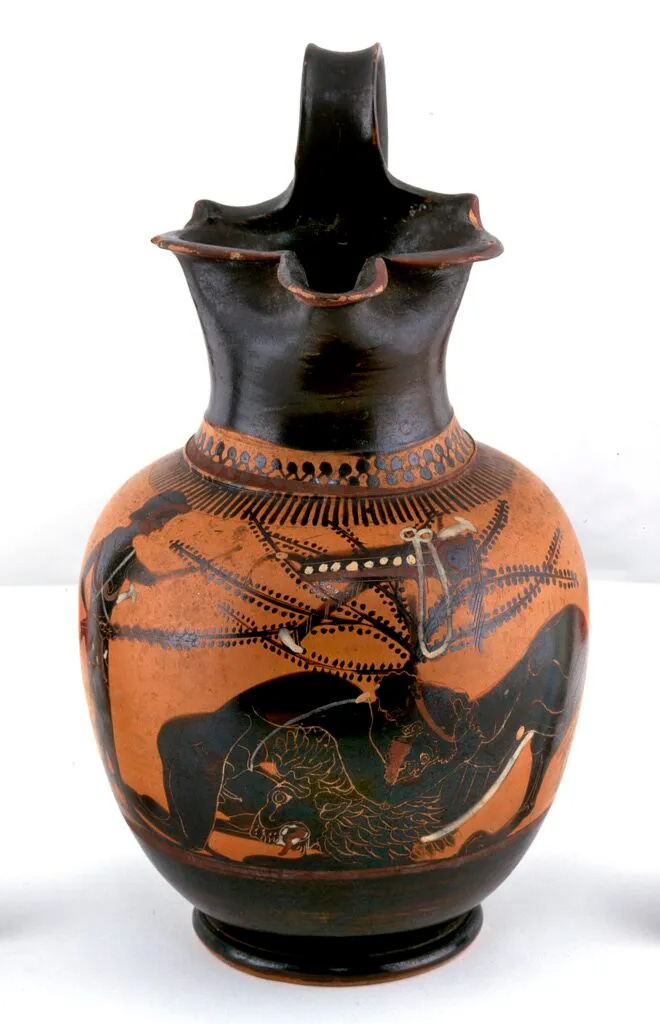

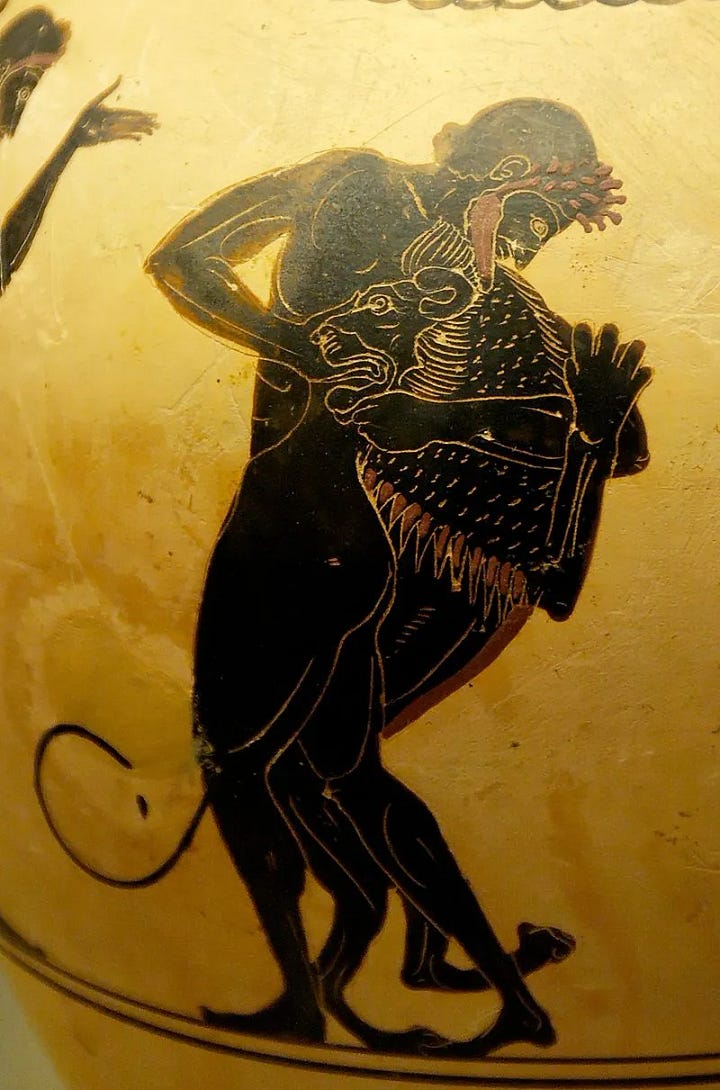

The creation of pankration has been attributed to mythic heroes such as Theseus, whose resume included slaying the minotaur and founding Athens, and Heracles, known for his 12 labors. Heracles is said to have pioneered pankration's fighting techniques during his battle with the Nemean lion, the first of his labors. In the Bibliotheca of Pseudo-Apollodorus (1-2 century CE) we read that Heracles was forced to resort to innovative full-contact combat after discovering the creature’s skin was impenetrable to his arrow. Heracles wrapped “his arm around its neck held it tight till he had choked it.” The maneuver, depicted on a 5th century BCE terracotta wine jug (oinochoe), would go on to be deployed by many a pankration competitor.

Pankration’s name speaks to the nature of the game itself and its exaltation of physical domination as athletic achievement. Pankration means “all force.” It's believed that competitors were minimally constrained as they attempted to achieve the goal of physically overpowering their opponent. The few rules that were imposed, explained the third century CE author, Philostratus the Elder, included the prohibition of eye gouging and biting. Finger breaking appears to have been allowable. Each fight ended when one of the fighters submitted to the other. Submission was expressed by raising an index finger or simply going unconscious. With so few guidelines it's no surprise some of the combatants died in competition.

According to Philostratus, pankration was “the noblest of the contests held at Olympia.” Comprehending the character of pankration helps us understand why the ancient Greeks didn’t treat the Olympics as a set of “games.” Pindar wrote,

“With the help of a god, one man can sharpen another who is born for excellence, and encourage him to tremendous achievement. Without toil only a few have attained joy, a light of life above all labors.”

Olympic competitions were envisioned as ordeals over which the athlete sought to triumph. In A Brief History of the Olympic Games, classics scholar David C. Young argues that the term “Olympic Games” is a poor translation of the Greek Olympiakoi agones. The ancient Greeks did not envision their athletic competitions as “games” or a form of “play.” The Greek word agones, from which our word for “agony” is derived, is better translated as something like “struggles” or “contests.”

Not only did the ancient Greeks not give out participation trophies, they didn’t give out silver or bronze medals either. The only athlete honored at the end of an ancient Olympic contest was the victor. These were winner-take-all contests. To win the early games meant not only to win material prizes, it meant that competition receiving your name. This was an honor akin to having the year named after you. As Stephen G. Miller put it in his book, Ancient Greek Athletics:

“the victor gave his name to the entire four-year Olympiad. We thus know the names of nearly every ancient Olympic stadion winner because the ancient Greeks used Olympiads to reckon time. For example, we say that the Battle of Marathon took place in the late summer (September 12) of the year 490 B.C., but ancient Greeks would identify that year as the third year of the Olympiad in which Tisikrates of Kroton won the stadion for the second time.”

We are sometimes occasioned to see ourselves as unique, culturally speaking, for placing so much emphasis on sports. Yet the ancient Greek example reminds us that there is something of a precedent, for better or worse, for placing athletic competition at the center of our social-cultural world.

For much of the ancient Greek world, athletic victory was an intrinsic good. To win, either in combat or in competition—and the two were understood to be bound up with one another—was to exhibit arete, excellence or the activation of one’s fullest human potential. For this reason, athletes sacrificed not only their temporary wellbeing in pursuit of victory in grueling combat sports, but also, on rare occasions, their lives.

In at least two noted contests, dead Greek athletes were crowned victors. According to the ancient author Pausanias, the boxer, Creugas, was crowned victor during the Nemean Games, around 400 BCE. and earned a statue in Argos after dying in a match against Damoxenus. The two men decided to take turns dealing out their hardest blows in an attempt to expedite a lengthy match. When dealing a thundering blow to Creugas’ ribs, Damoxenus extended his sharp finger nails and penetrated his opponent’s skin. With “the force of the blow he drove his hand into the other's insides, caught his bowels, and tore them as he pulled them out.” Creugas was instantly killed and Damoxenus disqualified. Why? Because Damoxenus had violated the agreement of exchanging singular punches when he issued secondary blows to his opponent when he penetrated his flesh.

Arrichion’s Olympic victory in pankration is perhaps most illustrative of the seriousness of ancient Greek attitudes to athletics. Arrichion not only died during athletic combat, he allegedly sacrificed his life, willingly, to prevail during his 568 BCE contest. Arrichion was said to have been caught in a stranglehold by his opponent but refused to submit. Instead, he used his final moments of consciousness to break his opponents’ toes, according to Philostratus’ account, or dislocate his foot from his ankle, according to Pausanias’ second century CE account. The pain suffered by the unnamed opponent caused him to quit the match only to discover Arrichion dead and declared the victor. Philostratus wrote that Arrichion not only “conquered” his opponent but also “all the Greeks” as the match’s spectators roared with applause and celebration for his victory.

“Is anyone so without feeling as not to applaud this athlete? For after he had already achieved a great deed by winning two victories in the Olympic games, a yet greater deed is here depicted, in that, having won this victory at the cost of his life, he is being conducted to the realms of the blessed with the very dust of victory still upon him. Let not this be regarded as mere chance, since he planned most shrewdly for the victory.”

Philostratus’ question about the praiseworthiness of Arrichion’s victory was not meant to be seriously contemplated. Yet many of us today do ask the question, What is the right price to pay for athletic excellence? What should the individual athlete be willing to endure and what should the society itself permit as an acceptable level of harm or risk?

Still there is something inspiring, many of us will concede, in a human being deciding precisely how they wish to live and, also, how, when, and what they are willing to die for. Whether we celebrate or condemn a soldier’s self-sacrifice for an ethical commitment (such as trying to awaken a nation’s conscience to the wholesale destruction of a people) or an athlete’s self-sacrifice for victory, we would do well to honor their lives by thoughtfully contemplating what it is that we each believe is worth living or even dying for.

The Boxer

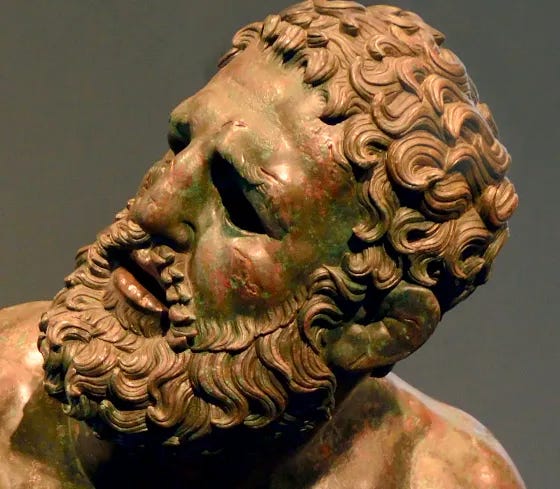

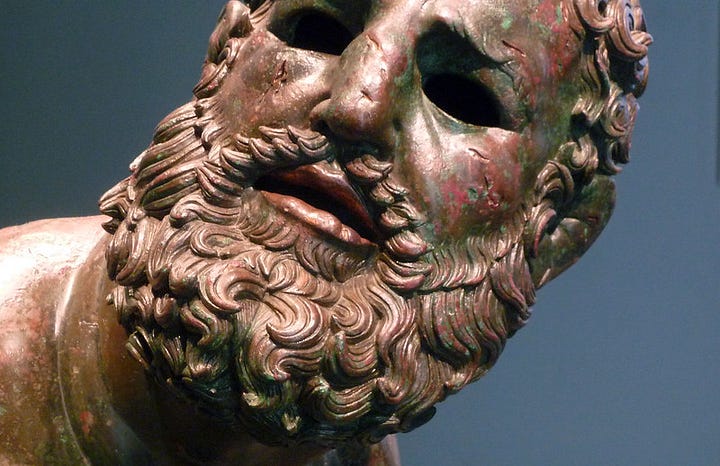

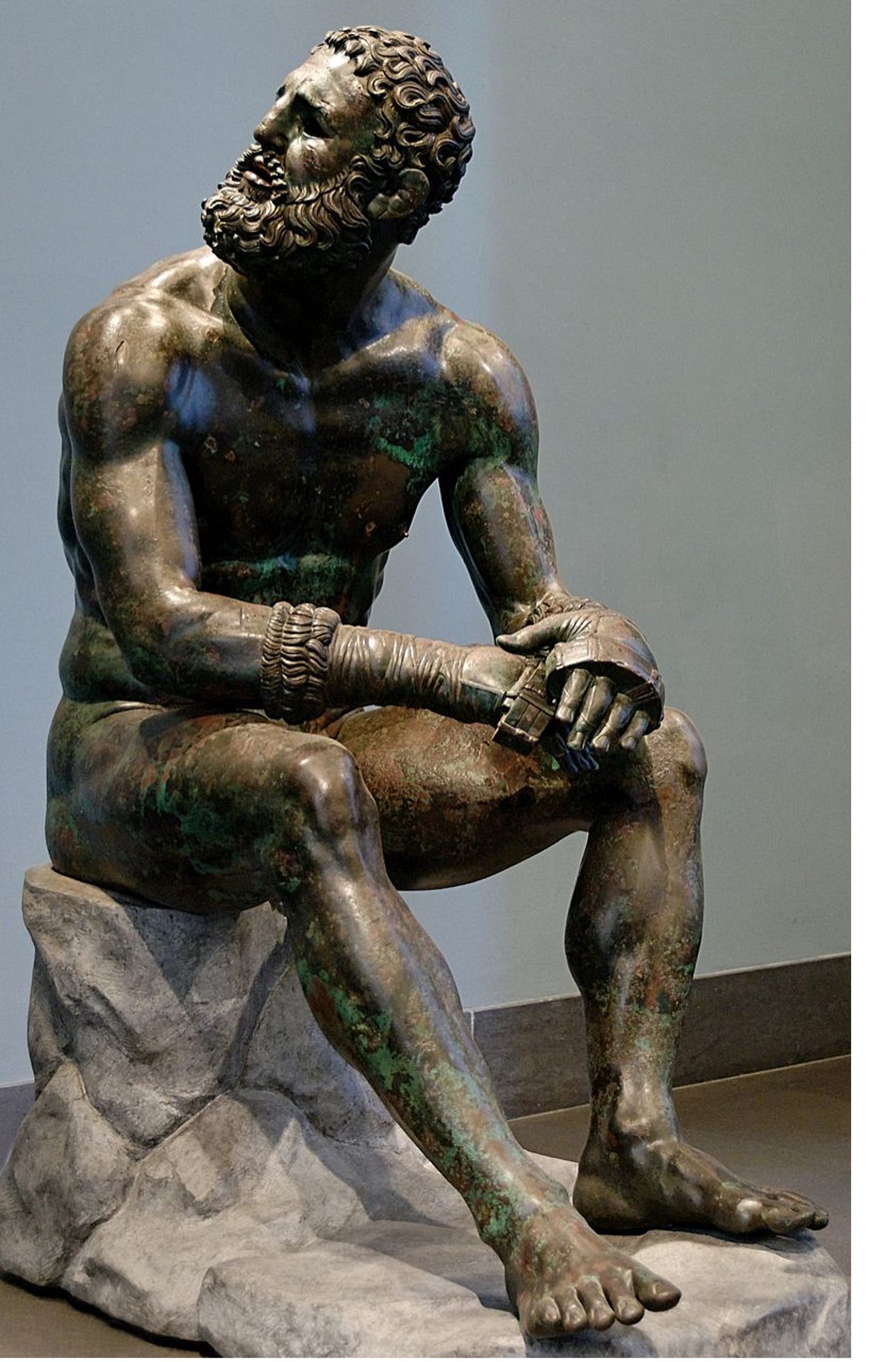

As dangerous and disfiguring as pankration seems to have been, one of the great Olympic champions of ancient Greece regarded boxing as more injurious. During the 216 BCE contests, the Theban, Kleitomachos,2 won both the boxing and pankration events. He was just the second, according to Pausanias, to have ever done so. The fighter also achieved the rare feet of winning the wrestling, boxing, and pankration events in a single day during the Corinthian Isthmian contests, held the year before and the year after the Olympics. Pausanias reports seeing a statue of Kleitomachos at Olympia exalting his achievements. Sadly, the statue is lost to the ages. Other works such as “The Boxer at Rest,” crafted of bronze in the third or second century BCE, offer a vivid window into past combat competitions.

The fine detail of the hair and the face allow us to recognize the humanity underlying the muscular brawn. Perhaps the fighter is awaiting the start of a match, contemplating his first moves. One thing is for sure, he was not between rounds since ancient Greek boxers had no such respite from their fisticuffs. Like combatants in the pankration, he would fight his opponent just as we see him here: naked. Indeed, the word “gymnasium” is derived from Greek terms referring to being naked and public places for exercise. In other words, a gymnasium was, for the Greeks, a public place for men to partake in athletic training in the nude. Returning to the resting fighter, we see that he adorned nothing but wrist wrappings and a pair of “gloves” which, upon close inspection, were meant more for the protection of one’s own knuckles than to soften any blows.

In the 212 BCE Olympics Kleitomachos’s request was granted to have the boxing event held after the pankration event. The fighter believed the injuries sustained from boxing were greater than those from pankration. Looking closely at the face of the “Boxer at Rest” reveals the toll these boxing matches took on the men’s bodies. The strength and majesty of the boxer is tempered when we recognize the cuts and likely scars forming a rough and uneven topography upon his nose, forehead, eyebrow, and cheek.

Here was a man not engaged in mere “sport” but who put his whole self—we might even say “sacrificing” his whole self—in pursuit of victory. And only the victory of first-place would do since their were no second or third place honors. Does this unnamed fighter evoke our admiration—do we marvel at his stoic strength, his ability to endure a panoply of injuries? Do we recoil at his brutalized visage, seeing only a masterful illustration of the violent objectification of the male body and person? Are we left wishing to follow in his footsteps or leading him to more human endeavors?

Asking Humanistic Questions and Thinking Critically about Popular Culture

Contrasting contemporary Olympics with its ancient predecessor generates many worthwhile questions. Should we embrace the ancient Greek’s winner-take-all vision of success or is our acknowledgment of second and third place a wise innovation? What are we to think of the absence of team sport in the ancient Olympics? Are there significant cultural differences between our team sports and those athletics pitting individuals against each other? Does the exaltation of star talent—Lionel Messi, Tom Brady, Lebron James—undermine the essence of team sport or is it a way of infusing the best of individual and team sport together?

More generally we can ask, are we mistaken to call contemporary athletics “games”? Or is there insight in calling into question the notion that athletic competitions are worth sacrificing our wellbeing or lives for?

And what of pankration? Are our Olympic Games impoverished for their omission of this war of physical wills? To what extent is arete or human excellence exemplified in a sport such as pankration? Were competitions such as these really worth the likely prolonged injuries endured from the matches?

Pankration also invites us to contemplate rules. Some perceive rules or obligations as purely negative impositions. But rules can also create opportunities that do not exist in states of rulelessness. We’re thus led to ask questions such as: What kinds of rules are necessary to make for good sport? When does the absence of rules make for an unfair and ultimately less satisfying sport? How should we balance our appreciation of strength, agility, endurance, and the capacity to endure brute force?

Contemporary sport culture doesn’t permit fighting to the death. The health of individual athletes is increasingly treated as a matter of primary concern. Yet we might do well not to proclaim our virtue and total success just yet. Though contemporary Olympics omits pankration, we know that boxing and other combat sports such as mixed martial arts are as popular today as ever. Not to mention American football. This despite a growing body of research showing the dangers of such “contact” sports.

In “Neurologic Health in Combat Sports,” medical doctor, Tad Seifert writes that combat sport participants face “significant risk” of concussion and “lasting brain damage.” Seifert notes that the very nature of combat sports puts people’s wellbeing at risk: the aim is “to deliver a concussive injury to the opponent….” Concussed athletes suffer much more than temporary harm. Seifert cites research estimating

“20% to 50% of former boxers have symptoms of chronic brain injury. Combat sport athletes are exposed to thousands of blows to the head over the course of their careers, with the cumulative endpoint often being that of chronic neurologic impairment.”

Yet the fact that combat and other “contact” sports are dangerous does not, in itself, refute them. As with the ancient Greeks, many today view such sports as more than a means but also an ends of life. Many view athletics as part of their purpose as human beings.

We are thus led to asking important humanistic questions: Has the individual athlete authentically chosen this path, or have they had it foisted upon them by cultural or familial expectation? What role does financial necessity play in shaping people’s decisions to pursue sport? Is sport worth the required investment—in terms of time, effort, physical toll? What should the upper limits of sacrifice be for us as individual athletes? What forms of regulations should we adopt as a responsible society? How do we honor the competitive spirit in humanity while also honoring the dignity of the athlete as a person of infinite moral value? What’s more, how do we balance our desire to keep individuals safe with a respect for individual autonomy?

It's also worth considering the under-acknowledged relationship between sport and political power. It's no accident that combat sport has its origin among soldiers and in warfare. Even as we acknowledge that some individuals may wish to entertain greater physical risk than others we are still faced with larger ethical questions. What values do our contemporary combat sports promote in society? Which of these values cultivate goodness in individuals and the wider community? Do our sports cultivate and endorse any beliefs that are harmful to the wider society? If some sports inspire unethical behavior and cultivate harmful values, is it possible to reform them or at least minimize their detrimental impact? Or should they be prohibited?

Cultural Criticism, Then and Now

We should also be careful not to think that these kinds of ethical questions are specific or unique to present day society. The presocratic philosopher, Xenophanes (570-478 BCE) articulated a range of criticisms against sport including the implied exaltation of “strength” over “wisdom.” He contended that there are no worse “evils that exist in Greece” than “the tribe of athletes.” Athletes, he contends, are ruled by their stomachs and do not “learn how one should live.”

Xenophanes insisted that crowns should be reserved for “wise and good men” and those who would lead “the city best by being wise and just” or liberate “the city from evil deeds, ridding it both of battles and of civic strife. For noble deeds like these are good for the whole city and for all Greeks.”

Xenophanes’ ancient cultural criticism reminds us, also, that the art and practice of taking popular culture seriously is not new. Whether or not we accept his analysis of ancient Greek athletics, we should appreciate the logical implication of his analysis: the awareness that human beings learn as much or more through life’s classroom than anywhere else.

Even the “games” we play require critical examination. As the cultural studies scholar Stuart Hall explained, popular culture is itself an arena or “battlefield” of ideas. And on this complex battlefield we find “resistance and acceptance, refusal and capitulation.” Where do we find ourselves on this battlefield and what are the repercussions of failing to recognize the unseen competition over ideas waged within the competition before our eyes?

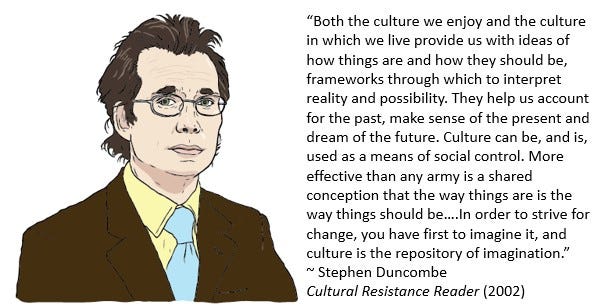

By critically examining culture we learn to recognize how special interests utilize ostensibly “apolitical” arenas of popular culture—from movies, music, and sports—to advance particular visions of what a good society is. Cultural studies scholar, Stephen Duncombe wrote:

“Both the culture we enjoy and the culture in which we live provide us with ideas of how things are and how they should be, frameworks through which to interpret reality and possibility. They help us account for the past, make sense of the present and dream of the future. Culture can be, and is, used as a means of social control. More effective than any army is a shared conception that the way things are is the way things should be…. In order to strive for change, you have first to imagine it, and culture is the repository of imagination.”

And sport achieves nothing better than creating largely agreed upon frameworks for understanding fairness, responsibility (individual versus group), and achievement (winning and losing versus cooperative athletic goals).3

But sport does not have to be an arena of “indoctrination.” Sport can become an opportunity to critically examine not just how best to play a given “game” within the existing rules, but also how the very structure of the game—the rules and goals—generate particular outcomes. Outcomes that may favor or fail to favor individuals and teams with particular bodies and abilities.4 But we can open ourselves to manipulation by failing to recognize the power popular culture has in bypassing our rational minds and shaping us with moving but manipulative spectacles. In Dream or Nightmare: Reimagining Politics in an Age of Fantasy (2019), Duncombe explained that a spectacle

“is a way of making an argument. Not through appeals to reason, rationality, and self-evident truth, but instead through story and myth, fears and desire, imagination and fantasy.”

We are all more suspectable to ingesting ideas that are furtively woven into riveting stories, moving musical scores, and glamorous movie stars. We are equally captivated by the aesthetic feast of grand athletic competition. As the philosopher Sissela Bok has reminded us, Roman authorities used gladiatorial combat as a method of social direction and control.

“Violent spectacles kept the citizenry distracted, engaged, and entertained and, along with reenactments and celebrations of conquest and sacrifices abroad, provided the continued acculturation to violence needed by a warrior state.”

We would do well to ask ourselves, what might our sports be keeping us distracted from? And are we permitting flawed beliefs and ideals to uncritically infiltrate our worldview as we are so engrossingly entertained?

What Comes Next? Dreaming of Sport to Come

The fact that there are many sports in our contemporary Olympics that the ancients never even thought of—breakdancing, for example—offers an important insight: We need not be prisoners to the past. We should certainly embrace the best left to us from our human ancestors, but we should also know how to improve upon and, at the right time, abandon parts of that cultural inheritance. Are there some sports that we need to simply let go of in favor of new sports better reflective of contemporary needs, interests, and values? In what ways might our being beholden to sport-as-usual thwarting creative thinking about the possibilities of sport?

We are left to ask not only whether or not breakdancing deserves to be an Olympic sport, but also what makes something a sport in the first-place. Philosopher Bernard Suits argued that the traditional notion of all sports as being identical with competitive games was mistaken. Instead, he argued that there were at least two kinds of sports. Athletic performances are one kind of sport. These include activities such as gymnastics, diving, free-style skiing, cheerleading, and breakdancing. They lack referees and require judges to assess the artistry of the performances. The second and more widely recognized type of sport is comprised of athletic games. These activities, including soccer, basketball, baseball, and football, are governed by clear and precise rules requiring referees.

Should our notion of sport include performances? What reasons are there, if any, for excluding performances like “breaking” from our conception of sport? Is our exaltation of rule-based sport over performative-aesthetic sport due to cultural conditioning or reasoned objections? In her germinal 1979 paper, “The Exclusion of Women from Sport,” the feminist philosopher Iris Marion Young wrote that the limits imposed by male dominance over sport had not only robbed women of their right as human beings to participate fully in sport but had also hindered the flourishing of our collective “sport imagination.” “Both the liberation of women and the liberation of sport,” she wrote, require “the invention of new sports and the inclusion in our concept of sport of physical activities presently outside or on the boundaries of sport.”

Pondering the risk of restraining innovation, I can’t help but think of just how terrible the mechanics and game play of “classic” boardgames like Monopoly are compared to the instant classic Ticket to Ride (2004). I shudder at the thought of being stuck playing yet another slow-moving marathon game of Castle Risk (1986) when I could have been playing a dynamic, inherently satisfying game of Ticket to Ride: Old West (2017). By analogy I’m left wondering, what athletic competitions do we currently have that we should play more often and give greater visibility to? And what new competitions have yet to be created due to our unthinking loyalty to the past?

Invite Dr. Nall to Speak

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook or by leaving a comment.

Though many claim otherwise, it is unlikely that the Christian emperor Theodosius I was responsible for outlawing the Olympics. See Caillan Davenport and Shushma Malik, "Myth busting Ancient Rome: did Christians ban the ancient Olympics?," The Conversation, February 20, 2018

Alternatively referred to as Cleitomachus.

It also teaches less recognized lessons in power—who makes the calls and who takes them; who owns and who works—and purpose—what is worth doing.

Reality TV show games involving physical challenges been particularly good at helping us think different about different people with different bodies and abilities. In episode one of season two of The Traitors: U.K, contestants were required to complete a puzzle. But before doing so they first had to escape from being tied to a pole. It turned out that one of the contestants had a prosthetic hand that allowed her to easily slip out of the ropes and begin helping her teammates. What would have generally been considered a disability became a helpful attribute.

This is another fantastic and excellently crafted piece delving into one of today's most relevant topics: sports. Sports promote physical, mental, and spiritual well-being and positive social and cultural change. In a way, skilled athletes, like artists, help advocate for love, peace, human rights, and global equality. Some sports, such as boxing, involve harming one another only for entertainment rather than survival or self-defense, which are considered unjustifiable acts of violence, regardless of the pursuit of glory or gold medals.

Due to our obsessive desire to win, we honor and praise our athletes not for their moral integrity and courage but for the many medals and victories they brought to our favorite teams. For example, some famous players are egoistic, racist, and supportive of genocides against innocent children. They are enslaved by greed and shamefully lack passion and loyalty to their teams or nations. They are willing to sell themselves for whoever pays more, similar to slavery during ancient times.

Like Zeus, the ancient Greek and Roman Olympian God was praised and worshiped not for his wisdom or moral virtues but because of the fear instilled by his evil power. Zeus's actions were driven by darkness, paranoia, and fear of losing his dominion over humans. To remain in power, he did everything to reduce the population, including orchestrating natural disasters, spreading diseases and hunger, and instigating civil wars, which seems relevant and inspiring for the current narcissistic leaders in the modern world. Apollo is one of the Olympian deities and the patron of homosexuality; due to his compulsive obsessions, he couldn't endure rejection. And despite his extraordinary talents, he was a women rapist, similar to his father, Zeus.

When the ancient Greeks realized their Goddess or leaders' darkness, greed, selfishness, and psychosis, they developed Stoicism. Stoics viewed Socrates as a role model and adopted his ideas to suppress inner rage, fears, aggression, and violence, protest against injustice, and not accept fatalism. Socrates called for questioning everything for positive social change. His views threatened the status quo in several ways and led him to death by the unjust judgment of corruption and impiety.

Our current misinterpretation, distortion, and manipulation of this philosophy, which are done mainly through oppressors to fulfill their agenda, have resulted in widespread emotional numbness, detachment, and the acceptance of fatalism, hindering any positive social or cultural change. Instead of inspiring hope and dreaming for a brighter future, we have confined ourselves to our comfort zones by twisting the primary meaning of their sayings.

For example, Epicurus's quote, "Not to spoil what you have by desiring what you don't have." This quote initially referred to "Non-stopping greed" and an insatiable, never-ending desire to acquire more of something, like money or possessions, regardless of already having enough, essentially a relentless pursuit of wealth with no sense of satisfaction or limit; it implies a person who is always wanting more, even if it means harming others or compromising their ethics to get it. But he never meant to prevent us from dreaming, seeking happiness, or hoping for a better tomorrow as our manipulators twisted.

Women in ancient Greece had no rights to participate in politics or sports. Today, human rights allow any woman to participate in boxing and combat games in the Olympics, and ironically, by the name of gender equality and human rights, any man inhumanly can beat a woman as the world watches. They are not only legalizing violence against women but making it an enjoyable entertainment tool for our "psychopaths." Due to our delusional disorder, and fake women's rights, we are willing to support any oppressive system that funds bombing, torture, rape, stillbirth, abortion, and displacement of other women who belong to different races, low-income countries, or religions.

Their deceptive notion of equality hypnotized us and captivated our attention while overlooking the millions of women refugees who were displaced from their homes and countries between 2011 and 2024 due to conflicts eternalized or supported by these authoritarian, unjust systems. These women living in camps face ongoing threats of femicide, trafficking, gender-based violence, forced abortion, and suicide.

Sadly, in ancient Greek mythology and during darker periods of history, women were often more dignified than they are today. We no longer adhere to their false human rights, democratic values, and ideologies. We no longer need their permission to speak. Instead, we should focus on reclaiming our dignity, as the King once stated: "One's dignity may be assaulted, vandalized, cruelly mocked, but it can never be taken away unless it is surrendered."

Your willingness to offer your wisdom and knowledge on such a vital and potent topic is highly appreciated.