The Other 9/11: Movies, Militarism, and What's Missing from Popular American Consciousness

Part IV of a series exploring the intersection of movies, popular culture, and the U.S. military

The silver screen lights up with roaring jet engines cutting across a blood orange sunset. The pilot unleashes a torrent of missile fire on his foreign adversary just as Zeus might have hurled his crackling bolt of lightning at Typhon. The target is struck. Red and blue flames erupt as the sunrise of war. The enemy is defeated, and the heroic American protagonist calmly radios his victory to base against the sonic backdrop of a popular radio hit. Riveted in cinematic-awe, it never crosses our mind that a government agency has helped prepare this four-course aesthetic feast that gluts our appetite for entertainment.

Few in the general public are aware of the fact the Department of Defense has participated in movie making for more than 100 years. The DoD’s entertainment office is particularly interested in ensuring the mechanics of war and military ritual are accurately rendered on the big screen. The DoD pays comparably little attention to representing the ethical complexities and personal suffering often accompanying military service.

In place of sustained dialogue about the prudence of continually investing hundreds of billions of dollars in military spending, we find cinematic spectacles of war like the DoD supported movie, Top Gun: Maverick.

Pentagon backed portrayals of the U.S. military insulate us from contemplating our nation’s historical relationship to war and military power, and its trajectory as the balance of global power shifts.

Read the first three parts of the series exploring warfare and popular culture: (I) Giving Veterans More than "Thanks,” (II) Going to the Movies...with the Pentagon, and (III) The Top Gun Effect: Why Hollywood Movies Matter to the U.S. Military,

What’s Left Out

The Pentagon’s successful influence over movie making conveniently makes it more difficult to recognize what is missing from Hollywood’s cinematic representations of warfare. Our movies and the wider culture portray a freedom loving nation that reluctantly fights for the right reasons, even when it makes mistakes. The general public does not learn of our nation’s ongoing support for autocratic monarchies such as the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and Kingdom of Bahrain even as each nation has a lower “freedom” score than Iran. (See the non-profit human rights' organization, Freedom House’s ranking of Bahrain and Saudi Arabia, and note the State Department's 2022 report on Bahrain.)

Pentagon-backed movies like G.I. Joe: The Rise of Cobra (2009) tell stories of good-guy American military figures trying to stop evil arms dealers (Destro) “from plunging the world into Chaos.” We do not expect such entertaining spectacles to educate. But we tend not to realize how they obscure reality through fictional narratives that actually invert reality. One would think it important to know, for example that between 2017 and 2021, the United States was responsible for 39% of global arms sales, supplying weapons to more than 100 countries. (This figure increased to 40% for the years between 2018 and 2022.) The top recipient of our arms’ sales has been the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, a nation fighting a devastating war in Yemen.

In 2021 sales of global arms and military services grew to $592 billion. Of this total 40 companies in the U.S. accounted for $299 billion, more than half of all sales. One of the U.S. companies responsible for producing these exports is Lockheed Martin, the company that teamed up with Top Gun: Maverick filmmakers to help conceptualize the imagined technology features in the film.

As of October 2022, the United States had sold $65 billion dollars in weapons to 34 out of 46 armed global conflicts. In December 2022 the Biden administration approved over $425 million in arms sales to Taiwan amidst escalating tensions between Taiwan and China. Another $619 million in arms, including missiles for F-16 fighter jets, was approved on March 2, 2023.

The Other 9/11: September 11, 1973

Few Americans are familiar with our nation’s well-documented history of directly or indirectly overthrowing other nations’ governments. This is perhaps most glaringly indicated in the fact most think of 9/11 as a uniquely American experience of national trauma and terrorism. Few know that the U.S. government undertook covert action to undermine democracy and stability in Chile exactly 28 years before our 9/11.

In a 1975 Senate report, "Covert Action in Chile 1963-1973," senators drew on government documents and testimony to detail our nation's "extensive and continuous" role in directly manipulating Chilean political society. At the direction of President Nixon, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) actively funded the “manipulation of the press,” political parties opposed to the candidate disfavored by the U.S., and even funded a political organization "whose tactics became more violent over time." The CIA sought to shape the outcome of Chilean elections to prevent the election of Salvador Allende, a medical doctor determined to address poverty and rampant malnutrition in his country.

After Allende overcame U.S. government interventions to become president, the CIA authorized an $8 million budget for opposing the new president. The money funded "direct attempts to foment a military coup." Eleven days after Allende’s successful election, in 1970, President Nixon told his advisors that he wanted to “make the [Chilean] economy scream” to undermine Allende’s presidency.

On September 11, 1973, Chilean military leaders, led by General Augusto Pinochet, seized power over the government through force. Allende committed suicide before air force jets bombed the presidential palace.

Though the 1975 Senate report failed to find evidence that the U.S. had directly enacted the successful coup, it did conclude that

"the CIA received intelligence reports on the coup planning of the group which carried out the successful September 11 coup throughout the months of July, August, and September 1973."

In other words, the U.S. government was well-aware its earlier efforts to undermine Chilean democracy were succeeding and, on the most conservative reading, stood by and allowed a military dictatorship to take over the country.

While claiming they were not directly responsible for toppling Allende's government, President Nixon and his Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, agreed “we helped them” and “created the conditions as great as possible” for its success. Kissinger complained that they would have been exalted for their role in undermining Chilean democracy had they done so during the 1950s. Nixon responded by saying, “our hand doesn't show on this one though.”

Kissinger and Nixon looked nostalgically to a time when the U.S. government fomented coups against democratically elected governments with impunity. In 1954, the CIA, acting at the behest of President Dwight Eisenhower, equipped and assisted a military overthrow of democratically elected Guatemalan president, Jacobo Árbenz. The U.S. backed military dictatorship resulted in the deaths of many thousands of civilians and a civil war that lasted until 1996.

Eisenhower also endorsed failed attempts to overthrow the governments of Indonesia (1957) and Syria (1956-1957) along with the successful 1953 overthrow of the democratically elected Iranian president, Mohammad Mosaddegh, in favor of a monarchy. Eisenhower explicitly suggested, then facilitated, the elimination of Patrice Lumumba, the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s first Prime Minister and leader of the nation’s movement for independence from Belgian colonial control. The U.S. government financially and diplomatically supported the military leader, Mobutu, who ousted Lumumba from office and took control of the country.1

Following the military takeover in Chile, the new leaders ordered soldiers to round up thousands of political opponents, including students and educators, and bring them at Chile Stadium in Santiago. Chile's Commission of Truth and Reconciliation concluded that more than 27,000 people were subjected to torture, including beatings, sexual violence, electrocution, forced consumption of excrement, and another 2,279 political opponents were executed or “disappeared.” In 2023, an international team of forensic experts determined that the Chilean poet, Pablo Neruda's death, during the September 1973 coup, was likely due to poisoning. Neruda was a friend of deposed president, Allende, and the findings bolster claims that the coup-regime was responsible for his death.

There is no ambiguity about the direct and lasting support the U.S. government provided to the military dictatorship, which held power until 1990. Following Allende's overthrow, the CIA actively supported the military dictatorship even as it rounded up civilian opponents, engaged in torture and summary executions. That help included “support for news media committed to creating a positive image for the military Junta.”

Chile's 2002 truth commission report concluded that the military dictatorship engaged in political assassinations, disappearances, torture, arbitrary imprisonment of many, exiled others, and attacked basic civil liberties of the population. Victims of the U.S. backed military dictatorship included two Americans journalists, Frank Teruggi and Charles Horman. The two men were abducted and murdered in the days following the coup.

Missing from American Consciousness

Blockbuster Hollywood movies do more than celebrate U.S. military prowess and glamorize military hardware. They miseducate the public with idyllic visions of U.S. military policies and warfare, and obscure a more complete picture of our nation’s role on the global stage.

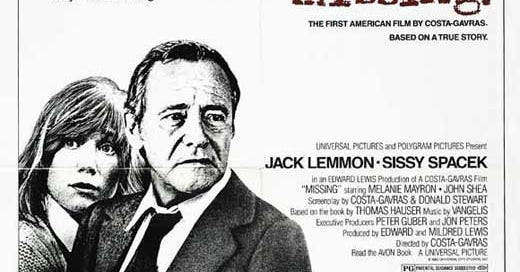

The Greek-French director, Costa-Gavras’s 1982 movie, Missing, is an exception to the prevailing Hollywood representation of U.S. militarism, reminding us that film has the twin powers of bringing truth to light as well as obscuring it behind cinematic spectacle.

Horman and Teruggi’s murders are the subject of the 1982 movie, Missing, featuring Jack Lemmon and Sissy Spacek. The film, which most certainly did not receive military support, tells the story of Horman’s father, Ed, flying from New York to Chile to join his son’s wife in desperately seeking to find Charles days into the coup. Adapted from a book of the same name by Thomas Hauser, Missing depicts Teruggi’s disappearance and suggests Horman was abducted and murdered because he discovered U.S. complicity in the coup.

Missing’s reception by those in authority reminds us of the power and importance of representation in popular culture. The film ranked third at the box office upon its release. It was also nominated for multiple Academy Awards, including best picture, best actor (Jack Lemmon), best actress (Sissy Spacek), and won in the category of best adapted screenplay.

The film was banned in Chile at the time of its release. And in 1983 it was removed from the U.S. market when the former U.S. Ambassador to Chile, Nathaniel Davis, filed a libel suit against the director and Universal studios. The libel suit, which was filed despite the fact the film did not name the former ambassador, failed, and the movie was released.

Missing was part of a cinematic cannon that began developing in the 1970s and 1980s that sought to dramatize governmental and military abuses of power. Such unsavory depictions—even if true—were also the motivation of later efforts to influence and shape cinematic depictions of the U.S. government and military.

As Horman’s wife, Joyce, recounts it, the couple was in the coastal city of Viña del Mar when the coup effort was initiated. The couple grew alarmed and planned to return to the capital, Santiago, where they lived. Charles also began documenting a heavy U.S. military presence happening alongside Chilean military equipment. Navy Captain Ray Davis, who commanded the U.S. Military Mission in Chile during the coup, offered to give the couple a ride back to the capital. During the drive, Captain Davis probed the couple about their political commitments and aims. The couple resolved to leave the country as soon as possible.

On September 17, 1973, Joyce and Charles kissed each other goodbye as they went to take care of errands. Later in the day Joyce returned home to find their home ransacked and her husband missing. When Joyce and Charles' father sought help from American officials, they were interrogated about their politics. Years later, in 2014, a Chilean court determined that U.S. Captain Davis had passed on what he had learned about the Horman’s to the coup government as it was rounding up political enemies. Davis’ actions were part of a covert intelligence gathering mission being run by the U.S. Embassy in Chile. A 1976 State Department memo, declassified in 1999, concluded that at best the U.S. may have provided or confirmed "information that helped motivate his murder" or, at worst, turned a blind eye to his being targeted for execution.

If you enjoyed this post please share it with others and like it by clicking the heart icon. Be sure to subscribe if you haven’t already.

Invite Dr. Nall to Speak

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook or by leaving a comment.

See Office of the Historian, "Foreign Relations of the United State, 1964-1968, Volume XXIII, Congo, 1960–1968," U.S. Department of State.

"You can't handle the truth!"

I wonder if they had a hand in that little chestnut.