In On Liberty (1859), English philosopher John Stuart Mill argued that silencing ideas we find repugnant is mistaken for multiple reasons. First, as difficult as it is to imagine right now, the idea we object to might actually be right. Silencing others implies that we know what can actually only be determined in dialogue: what is true and what is false. Mill wrote:

“There is the greatest difference between presuming an opinion to be true, because, with every opportunity for contesting it, it has not been refuted, and assuming its truth for the purpose of not permitting its refutation.”

Put differently, it’s one thing to be the champ because you overcame your challengers; it is something entirely different to ensure you’re the champ by ducking out on challenges to your title.

“Complete liberty of contradicting and disproving our opinion, is the very condition which justifies us in assuming its truth for purposes of action; and on no other terms can a being with human faculties have any rational assurance of being right.”

We prove the strength of our arguments when we boldly step into the ring with any idea that comes our way.

Truthfully, the boxing analogy isn’t really ideal because intellectual integrity is less about egoistically seeking to defend our existing beliefs and much more about open-minded pursuit of the truth, which means routinely subjecting our own beliefs to scrutiny and engaging in good faith consideration of ideas and beliefs that we find disagreeable. Critical thinking thrives on dialogue more than it does on intellectual fisticuffs. This much is clear from contrasting the experience of stepping into the “ring” of social media discourse with conversation rooted in honesty, integrity, and empathy. Yet the larger point remains that those of us who care about the truth must be willing to not only hear but genuinely consider views that we may find inconvenient, unsettling, and perhaps dangerously wrong.

Consider for example that many critics of Robert F. Kennedy Jr.'s views on vaccines and the government’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic have labeled his claims false often without engaging in the substance of his argument, with some going so far as to contend his ideas are so dangerous that they should not be debated or discussed in media at all. By contrast, host of the Bad Faith podcast, Briahna Joy Gray, engaged Dr. Vinay Prasad, a hematologist-oncologist and health researcher, in a productive, honest, and rather good faith examination of RFK’s arguments. Arguably viewers leave the conversation with greater clarity on Kennedy’s position, the critiques of his position, and areas where public health experts appear to share some common ground with Kennedy, even as they critique some of his conclusions.

The only way in which we can ever be assured that our beliefs about the world are true is if they are consistently open to challenge and interrogation. When we prohibit the expression of countering views, we outlaw the very mechanism by which we ensure the truthfulness of our beliefs. Recognizing our fallibility leads us to create space for people to express ideas we object to precisely so that we can determine which are right and which are wrong.

Finding Truth in Composites

The second reason it’s wrong to silence our opponents is that it's not often that our beliefs or those we object to are entirely right or entirely wrong. As Mill wrote,

“Popular opinions, on subjects not palpable to sense, are often true, but seldom or never the whole truth. They are a part of the truth; sometimes a greater, sometimes a smaller part, but exaggerated, distorted, and disjoined from the truths by which they ought to be accompanied and limited.”

The truth we are all after is usually pieced together through a dialectical process whereby we hold our beliefs, assumptions, and experiences up to the light of each other’s varied vantage points. Sometimes our thinking is confirmed, and sometimes we discover error. But we rarely have nothing to learn from one another, even those with whom we have many disagreements. Truth often emerges from a dynamic synthesis of variegated perspectives.

Avoiding Dead Dogmas

There's yet another reason to courageously stomach the free expressions of views that disgust us. In failing to courageously contend with those views we are sure are dangerously misguided, our righteous truths are likely to become what philosopher John Stuart Mill called “dead dogmas,” beliefs that we “hold” without genuine understanding and lively feeling.

Socrates’ frustrating encounters with supposedly Great Men unable to answer the most basic—which is to say foundational—questions about their areas of expertise illustrate the way in which even those beliefs and ideas most essential to our own purpose and identities can become perfunctory possessions, beliefs alienated from their possessor—idols. As Mill put it,

“however true [a strong opinion] may be, if it is not fully, frequently, and fearlessly discussed, it will be held as a dead dogma, not a living truth.”

Knowledge requires more than “having” the right opinion. Knowing entails understanding and being able to articulate the reasons for our correct belief. This is why Albert Einstein wrote, in “On Education” (1936), that

“knowledge must continually be renewed by ceaseless effort, if it is not to be lost. It resembles a statue of marble which stands in the desert and is continually threatened with burial by the shifting sand. The hands of service must ever be at work, in order that the marble continues lastingly to shine in the sun. To these serving hands mine shall also belong.”

Free expression and the democratic discourse it sustains enable us to renew our knowledge. By participating in dialogue—rather than squelching it—with views the same, similar, and outright opposed to our own, we maintain or restore the vitality and integrity of our beliefs. We are challenged with emerging from an all-too-easy egocentrism of self-righteous certainty; pushed to answer questions we too easily dismiss or fearfully avoid; inspired to realize new fine details in a truth we perfunctorily carry along like an appendage—an arm or a nose—without appreciation or scrutiny. And in this process we are sometimes called to decide between dogmatic rationalization or courageous acknowledgment that some of our beliefs are not entirely true if not embarrassingly erroneous.

Above all, freedom of expression and genuine democratic discourse ensure we remain alive to the truths we profess to care so much for. They test the authenticity of that commitment, challenging us to show that our beliefs are more than mere fragile idols but oaken truths capable of withstanding any wind.

Authentic intellectual confidence is the result not of strong feeling or confirmation by common sense, public authority, or the popularity of our belief. Genuine confidence in the rightness of our beliefs over those of others comes only when we have really heard and understood those views that contrast with and fully contradict our own. To know the whole of a subject, Mill wrote, requires to hear

“what can be said about it by persons of every variety of opinion, and studying all modes in which it can be looked at by every character of mind. No wise man ever acquired his wisdom in any mode but this; nor is it the nature of human intellect to become wise in any other manner.”

Our tendency to commit the strawman fallacy—of representing others’ arguments in an uncharitable and often easy to defeat manner—makes it all the more important to engage directly with the best and most authentic representations of those views we may not only object to but also loathe. As Mill wrote,

“…the peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is, that it is robbing the human race; posterity as well as the existing generation; those who dissent from the opinion, still more than those who hold it. If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth: if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error.”

This is why Mill goes so far as to say we should make space for the expression of even those views nearly all of us are sure are wrong.

“When there are persons to be found, who form an exception to the apparent unanimity of the world on any subject, even if the world is in the right, it is always probable that the dissentients have something worth hearing to save for themselves, and that truth would lose something by their silence.”

As an example, when I'm teaching students about the history of patriarchy I have them read works by great thinkers of the past that articulate their sexist and even racist arguments. I invite them to read the relevant primary source text, summarize the argument in question, and then assess it. For example, in one of my classes we read chapter 12 and 13, Book I, of Aristotle's Politics, where he argued males are the rightful rulers of females because “the male is by nature fitter for command than the female, just as the elder and full grown is superior to the younger and more immature.” He believed males were justified to maintain political and domestic control over women because women were by their very intrinsic nature emotionally and psychologically less suited to lead, to exercise autonomy.

Reading such arguments enables us to better grasp our objections to sexism and the weakness of sexist thought. Our own experience indicates that women, when not subject to repression but rather afforded opportunities to develop themselves and intellectually flourish, are as capable of exercising agency and leadership as men are. We also learn an important lesson in intellectual humility. We are left to ask ourselves, if such accomplished and competent thinkers could be so wrong on such an important matter, what might we be wrong about, today.

…bell hooks was asked if she would ever support canceling a speaker who advocated for repugnant ideas such as racism and Naziism. Her answer was no.

Rather than seeking to suppress such an argument we do better to meet it head on and expose its errors. The argument might be insulting or morally reprehensible, but we ought to be able to recognize the difference between an imminent threat to our well-being and a discomforting idea. What’s more, strong feelings including disgust, though potentially indicative of insight, are not immune to error. Thus even those ideas that repulse us present opportunities to gain greater understanding of the rational—or maybe irrational—basis of those feelings.

Returning to Mill's point, confronting opposing views can stimulate insight and nourish commitments. This was a point reaffirmed by law scholar, Robert P. George, and philosopher Cornel West, who was bell hooks’ friend. In 2017 the two friends, who happen to hold contradicting political viewpoints, co-authored a letter criticizing the growing trend of squelching freedom of speech on college campuses. Titled, “Truth Seeking, Democracy, and Freedom of Thought and Expression,” their letter highlighted Mill’s insight that we benefit from engaging with views that contradict or call into question our own, including those that are “shocking or scandalous.”

“…as Mill noted, even if one happens to be right about this or that disputed matter, seriously and respectfully engaging people who disagree will deepen one’s understanding of the truth and sharpen one’s ability to defend it.”

George and West go on to explain that those who prioritize intellectual integrity and truth over the idolatrous worship of their existing opinions “will want to listen to people who see things differently in order to learn what considerations – evidence, reasons, arguments – led them to a place different from where one happens, at least for now, to find oneself.”

That we are able to silence views we find mistaken does not guarantee their erasure from people's minds and from those areas of social life where they can still be expressed. In an interview on “Speaking Freely,” black feminist public intellectual, bell hooks said she supported freedom of speech even when it meant allowing the expression of outright hateful ideologies. hooks said that critical thinking and dialogue, not censorship, is what is called for in addressing flawed ideas.

“I think people need to know how to hear information and think critically about it. And that's usually—my whole thing is to say, what does it mean for us to hear something that we have to think critically about and that we can make a choice about as opposed to the idea that we should eliminate people saying certain things, people thinking certain things, take certain books out of the library. Well, let’s talk about those books, let’s talk about those ideas."

One reason we are sometimes discomforted by ideas that contradict our own is that we lack the knowledge necessary to reasonably defend our beliefs and show the weakness of those we detest. As Mill wrote, many of us allow luck and accident to verify our beliefs rather than taking responsibility to do our own thinking. So while we may happen to believe something which is true, we are unable to meaningfully support or defend the belief because we do not really know it.

“Ninety-nine in a hundred of what are called educated men are in this condition; even of those who can argue fluently for their opinions. Their conclusion may be true, but it might be false for anything they know: they have never thrown themselves into the mental position of those who think differently from them, and considered what such persons may have to say; and consequently they do not, in any proper sense of the word, know the doctrine which they themselves profess.”

To truly vanquish mistaken, erroneous, dehumanizing beliefs we must enhance our knowledge of the beliefs we claim to know but are susceptible to calcifying into alienated opinion and dead dogma. One way to do this is by rationally and empathetically engaging ideas opposed to our own most cherished beliefs. Though we are unlikely to change the mind of dogmatic adherents, we will enhance our capacity to convince those acting in good faith who are lured into misguided ideologies by superficially compelling and fallacious thought. Replacing enlivened dialogue with shallow decrees of what is right or wrong, permitted and unpermitted only dooms our cherished beliefs.

Silencing Ourselves by Logical Implication

Advocates of freedom of expression have and continue to argue that normalizing censorship tends to harm those with the least power and to thwart social progress. Censoring expression typically reinforces the dominant ideology of the present and undermines beliefs and ideas, be they spiritual, scientific, political, or ethical, that run counter to those in power and the status-quo. In the “Speaking Freely” interview, hooks was asked if she would ever support canceling a speaker who advocated for repugnant ideas such as racism and Naziism. Her answer was no.

“My response is always on behalf of freedom of speech. Basically, I always tell my students, if you look at the history of silencing, ultimately the people that get silenced are the dissident, radical voices. That any time we try to shut down people it in fact ends up being something that causes us to suffer more.”

bell hooks' contention that the right to express deplorable views ought to be protected accords with renowned public intellectual Noam Chomsky view. According to Chomsky, the suppression of speech has historically been used against individuals and movements seeking to challenge the status-quo and generate egalitarian societal change. In a September 5, 2018 lecture at the University of Arizona Chomsky explained that the principle that speech that is dangerous or harmful ought to be suppressed has

“almost invariably been directed against vulnerable groups, groups that deviate from what George Orwell once called the 'pervasive orthodoxy' and have been efforts to sustain a power, authority, and domination."

This view was at the heart of the American Civil Liberties Union’s decision, in 1978, to defend a neo-Nazi group's provocative march through the town of Skokie, a Chicago community comprised of hundreds of Holocaust survivors. The lead lawyer, David Goldberger was Jewish. Why would he defend the rights of an organization with such repugnant views? For one, because doing so preserves a principle that protects those seeking to generate progressive societal change. Goldberger explained,

"Central to the ACLU’s mission is the understanding that if the government can prevent lawful speech because it is offensive and hateful, then it can prevent any speech that it dislikes. In other words, the power to censor Nazis includes the power to censor protesters of all stripes and to prevent the press from publishing embarrassing facts and criticism that government officials label as ‘fake news.’ Ironically, Skokie’s efforts to enjoin the Nazi demonstration replicated the efforts of Southern segregationist communities to enjoin civil rights marches led by Martin Luther King during the 1960s.”

Though the case brought about great hardship for Goldberger, with accusations of being a self-hating Jew, he recalls with joy “instances of unexpected support” from courageous Holocaust survivors who “stood up to say that I was right to have represented the Nazis....They explained that they wanted to be able to see their enemies in plain sight so they would know who they were."

The views of Goldberger, hooks, and Chomsky are echoed in the ACLU’s March 2002 statement explaining “Freedom of Expression.”

“History teaches that the first target of government repression is never the last. If we do not come to the defense of the free speech rights of the most unpopular among us, even if their views are antithetical to the very freedom the First Amendment stands for, then no one’s liberty will be secure….

“Censoring so-called hate speech also runs counter to the long-term interests of the most frequent victims of hate: racial, ethnic, religious and sexual minorities. We should not give the government the power to decide which opinions are hateful, for history has taught us that government is more apt to use this power to prosecute minorities than to protect them. As one federal judge has put it, ‘tolerating hateful speech is the best protection we have against any Nazi-type regime in this country.’”

When Mill was writing, he was acutely aware of the persecution of those articulating beliefs that countered the religious orthodoxy of his nation. In 2017, journalist Glenn Greenwald documented instances in which European laws banning hate speech were used to punish those expressing virulent criticism of religion, police officers, and the nation of Israel’s treatment of Palestinians.

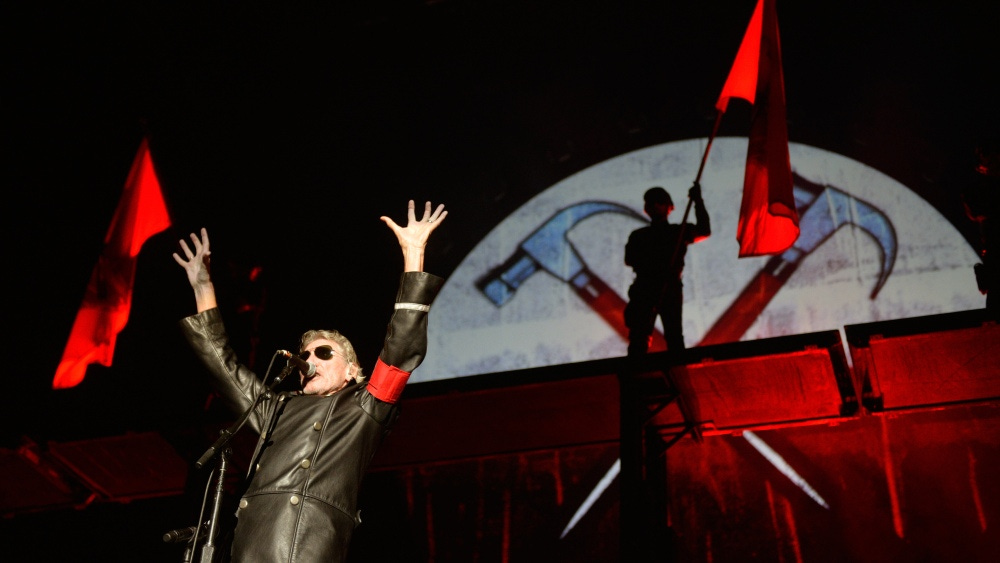

More recently, in March 2023, co-founder Pink Floyd, Roger Waters, was brought brought under investigation for "incitement to public hatred because the clothing worn on stage could be used to glorify or justify Nazi rule, thereby disturbing the public peace.”

Rogers insisted that his artistic intent was quite the opposite: he was mocking fascism, not celebrating.

“The elements of my performance that have been questioned are quite clearly a statement in opposition to fascism, injustice and bigotry in all its forms.”

According to Rogers, the legal inquiry was politically motivated in response to his consistent solidarity with Palestinians against what he views as the crimes perpetrated by the state of Israel. “Attempts to portray those elements as something else are disingenuous and politically motivated. The depiction of an unhinged fascist demagogue has been a feature of my shows since Pink Floyd’s ‘The Wall’ in 1980.”

The larger point is that restrictive laws might suppress expression—though not necessarily belief—we think is harmful, but they might also function to suppress expression some of us believe contributes to human progress.

Freedom of Speech and Democracy

We should stop thinking of the public square as a space where we are expected to articulate strictly perfected and always agreeable ideas. We must create space beyond our classrooms where people can speak authentically and frankly, even at the risk of expressing discomforting and potentially mistaken beliefs. Doing so would allow us to better understand each other and maybe even discover and work through some of our own prejudice and ignorance.

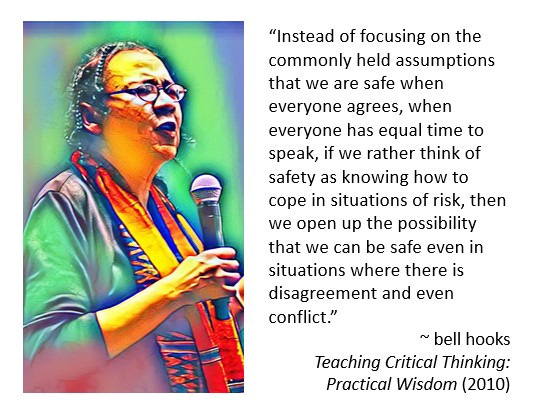

It goes without saying that feelings may sometimes get hurt in the process. But that is no justification for silencing genuine, open discourse. In Teaching Critical Thinking, hooks explained that the demand to create environments where people are unsettled has historically marginalized the voices and experiences of those with the least power.

Moreover, participation in democratic society requires a degree of emotional and intellectual maturity. hooks wrote,

"there is safety in learning to cope with conflict, with differences of thought and opinion...."

Drawing on her experience as an educator, public intellectual, and human beings navigating the complexities of life bell hooks urged us to recognize how insisting on agreement prevents us from working through our differences in non-violent dialogue.

“Instead of focusing on the commonly held assumptions that we are safe when everyone agrees, when everyone has equal time to speak, if we rather think of safety as knowing how to cope in situations of risk, then we open up the possibility that we can be safe even in situations where there is disagreement and even conflict.”

hooks’ point is not that we should allow others to personally or directly threaten our personal well being. She is not arguing that our feelings of insecurity ought to never be acknowledged and acted upon. As a member of a group of feminist thinkers who criticized dominant intellectual culture for failing to take emotions seriously, she was certainly not suggesting that feelings are never a valuable guide to making sense of the world. But she did challenge us to critically interrogate our notions of safety, and to acknowledge that feeling uncomfortable and even offended was not the same thing as being directly threatened. Indeed, her friend, Cornel West, remarked that the very purpose of a genuine liberal arts education “is to disturb and unsettle us.”

Undoubtedly, for example, the deeply convicted Christian may feel unsettled by the atheist’s arguments against the existence of God; and those who believe abortion is utterly immoral may be discomforted by those arguing that an embryo does not deserve the moral status of a person. The atheist and advocate or reproductive choice may be equally disturbed and unsettled by arguments against atheism and for the person hood of embryos. These are not trivial matters. Such arguments, right or wrong, could indeed powerfully impact the consciousness and practices of a society. Yet the articulation of these ideas not put anyone into immediate harm’s way. hooks challenged us to recognize that it is possible to be safe even as we navigate environments featuring intellectual-political-ethical risk and gravity.

Those tacitly or explicitly advancing censorship appear to misunderstand the nature of democratic societies and the extrinsic value of free expression. By embracing the democratic experiment, we commit ourselves to a process of constant dialogue and compromise with those in our community. That we will have disagreements—deep and potentially dangerous disagreements—is of no surprise. Some of the same disagreements we have with strangers in the wider public we also have with our own family members!

The value of free expression, beyond its intrinsic value as a component of autonomous, dignified living, is that it functions to facilitate non-violent conflict resolution. When we abandon democratic discourse and electoral politics as means to resolve our disagreements, we move closer to violent conflict. Freedom of expression is not only a safety valve to vent views some feel are unfairly marginalized, it can also function to enhance our critical thinking abilities including better grasping the beliefs—which is not to say right or truthful beliefs—of others in our society.

As West has highlighted, "dialogue, discussion, critical exchange, bold speech, frank speech" are all essential features of democratic society. In their 2017 letter, West and George contend that freedom of expression is vital to protecting ourselves “against dogmatism and groupthink, both of which are toxic to the health of academic communities and to the functioning of democracies.”

We should not falsely and naively insist that expression in the form of speech, music, art, and the like are ineffectual. When the same idea, symbol, or argument is repeated frequently and across multiple domains of cultural life, it can indeed come into power. When the idea is true then the results are good; if the idea is false then the results may be harmful. But there is no way to embrace democracy and honor human autonomy and truth without also permitting the free and open exercise of human thought. All the more reason for us to not shrink from robustly engaging with and, of need be, proactively combat precisely those ideas we find most odious.

Whose Speech is Dangerous?

In 1992, journalist John Pilger observed that Noam Chomsky had defended a neo-fascist heckler and asked if he believed the right of free expression extended to everyone. Chomsky replied,

“if we don't believe in free expression for people we despise, we don't believe in it at all.”

The principle of freedom of expression, argued Chomsky, in an earlier work, was meaningless if it only applied to expression we found agreeable.

“Among people who have learned something from the 18th century (say, Voltaire) it is a truism, hardly deserving discussion, that the defense of the right of free expression is not restricted to ideas one approves of, and that it is precisely in the case of ideas found most offensive that these rights must be most vigorously defended. Advocacy of the right to express ideas that are generally approved is, quite obviously, a matter of no significance.”

To help us think about the principle of freedom of expression and any potential limits to consider, we should ask ourselves, which of our deeply felt beliefs—about morality, religion, and politics—might be considered dangerous or even outright harmful by others in our society? What kind of argument might be made for censoring our free expression of these views?

What would it look like to empower a government with the authority to determine not only whose ideas were imminently dangerous, a very narrow designation, but also whose ideas and expressions were harmful or potentially harmful to individuals or society? How might our beliefs, including those that are not part of a majority opinion, be targeted by such a mechanism of the state?

Many in our nation, if given the power, would surely seek to censor the riveting Sam Smith performance I attended July 26, 2023, in Orlando, Florida, for its rather explicit representation of sexual liberation. (Smith’s performance of his new hit, “Unholy,” would likely be target number one.)

Plenty of vegans perceive steakhouse advertising campaigns and trending meat-lovers’ recipes as encouraging harm to sentient beings deserving of moral regard. It’s equally easy to anticipate plenty of people finding ethical veganism threatening to their culinary and broader cultural ways of life.

Many pundits aligned with the Democratic Party have explicitly rejected the wishes of 80% of Democratic voters who want President Joe Biden to participate in debates for 2024 presidential primary. They contend Biden’s chances of defeating Donald Trump in the general election could be jeopardized by debating primary contenders such as Marianne Williamson and Robert F. Kennedy Jr.1 And since a second Trump presidency would represent a threat to democracy itself and marginalized people, they argue, primary debates must be averted.2

Critics of Democratic primary debates have expanded their scope of concern to third party candidates like philosopher Cornel West, who is seeking the nomination for president with the Green Party.3 Democratic Party insider, James Carville, told CNN's Anderson Cooper that West's candidacy was “a menace” that threatened “the continued constitutional order in the United States.” Carville contends West’s candidacy is dangerous because he might take votes from Joe Biden and ensure a Donald Trump victory.4 Is it difficult to imagine that figures like Carville flipping the lever of censorship against third-party candidates deemed a threat to Democratic Party electoral success, if given the power to do so?

How dangerous might people of fundamentalist faith find expressions pertaining to agnosticism or atheism? How dangerous might those with deep moral objections to abortion find arguments and positive media representations supporting women's right to abortion? How dangerous might those in favor of the economic status-quo find contemporary socialists’ arguments?

Much of what we call social progress is a tapestry of repressed and condemned thought and expression that managed to prevail. Those committed to intellectual integrity—principled thought, consistency—have to recognize how dangerous some of their ideas are felt to be by others. It's only when we view this issue egocentrically that we think we stand on solid ground in calling for curtailing free expression.

Only when we realize that some of what we believe and advocate for is viewed by others as harmful do we grasp the implications of silencing speech we perceive as offensive, misguided, or dangerous. This is not to say we should embrace false equivalences—say, between someone saying that anti-racist thinking is dangerous to some just as explicitly white supremacist thought is dangerous to people of color. To the contrary, we should bring ethics and reason to our aid in offering a robust and compelling defense of the truth. But we must not forget that a democratic society doesn’t determine right and wrong by fiat nor can it take for granted as self-evident the truth of the very beliefs being debated within a society.

To think that we have "arrived," intellectually; that we can now bring controversial conversations to a close is the height of hubris. By withdrawing our commitment to freedom of expression we not only silence ourselves, but also denigrate the very means by which we test and enhance our knowledge: vibrant democratic discourse.

Please share and like this post by clicking the heart icon.

Invite Dr. Nall to Speak

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook or by leaving a comment.

Following the publication of this article Kennedy left the Democratic Party primary and initiated a run for president as an Independent candidate.

Aside from assuming that Biden is better than Trump, this argument takes for granted precisely that which debates and the primary election are meant to determine: who should be and will become the party’s nominee. It also presumes that debates would hurt their favored candidate even as the winner of the primary would be tasked with debating the winner of the other party’s primary.

Since the publication of this piece Cornel West left the Green Party and initiated a run for the presidency as an Independent.

An alternative to sounding the alarm about the “spoiler” effect of a third party candidate would be to insist that the favored candidate adopt policies and take political measures that would win them favor from those considering third party candidates. That this approach is sidestepped in favor of shaming voters and castigating candidates as threats to democracy tells us quite a lot about the political-ethical commitments of those in power.

continually surprised by low engagement on Substack with its much-touted "millions of readers..."

this is a very worthy effort, appreciate the amount of time it must have taken to write this.

Reality is and always will be the allegory of the three blind men and the elephant... a variation of Plato's cave, I prefer the elephant allegory because it so effortlessly demonstrates how all of us are accurately grasping our own small corner of experience in ways we don't even understand... that's the crux of the matter. understanding is a form of misapprehension. We're usually wrong about mostly everything. how do we make that easier by randomly ringfencing the aspects of reality that someone else had determined to be "off limits" from inquiry? if you dig deeper you discover their imperatives to shut you up are compelled by more complex motives... etc....

a society that is determined to not even try to understand itself has no future.

Thank you Jeffrey for a well-sourced discussion of the use of language in one of its most hermeneutic contexts. For me, it is Ricoeur's 'The Conflict of Interpretations' that remains the most salient collection of thoughts on this wider topic. My role as a thinker includes asking questions no one wants to ask, saying things no one wants to hear, and making more clear ideas and experiences that in fact everyone understands either tacitly or semi-consciously. These and 'corrupting youth', of course!