When Workers Shall Reign: Mark Twain’s Radical Vision of Worker Power and the Knights Who Inspired Him

Mark Twain and the Knights of Labor's Fight Against Gilded Age Capitalism

America has a habit of turning socially transgressive figures into trivialized celebrities. Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s explicitly revolutionary vision—of a spiritually destitute nation plagued by the “evils” of racism, militarism, and economic exploitation undergoing a rebirth—became a placid dream for equal opportunity. Albert Einstein’s pacifism and socialism are overshadowed by silly faces, one-liner quotes, and a generic appreciation for his brilliance. Helen Keller’s radical socialism, which included membership of the Socialist Party of America, and opposition to World War I became a narrowly defined legacy of the first deafblind woman to earn a four-year college degree. Perhaps no American thinker has been more domesticated than Keller’s friend, Mark Twain.

Today, Twain is considered one of the greatest and most influential American authors in U.S. history. His novel Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884) is ubiquitously read—or at least widely “assigned”1—and acclaimed for its cultural and literary significance. Twain has the additional accolade of being praised as a pioneering humorist.

As Twain would have found deliciously ironic, his exaltation has come at the cost of recognizing many of his most important ideas, ideas he put into words and writing. Twain was not only a staunch anti-imperialist but also an unequivocal critic of capitalism’s exploitation of workers. Twain believed this injustice would only be remedied when laborers of all trades formed a unified block capable of wresting power from those in political and economic authority. In learning of Twain’s radical2 vision of liberated workers wielding political power we not only reclaim a great American author as a champion of working people, we also open up a path to rediscover an inspiring history of labor struggle many in power want to be forgotten.

If you believe, as Twain did, that exploitation degrades us all, subscribe to Humanities in Revolt for stories that sustain the timeless fight for fairness and human liberty

Twain Believed Workers Should Hold Power

On March 22, 1886, Mark Twain delivered his tenth3 talk before the Hartford Monday Evening Club in Connecticut. The weekly men’s discussion group included intellectuals, clergy, jurists, elected officials, and businessmen. Some of the men were Twain’s close friends.

“Who are the oppressed? The many: The nations of the earth; the valuable personages; the workers; they that MAKE the bread that the soft-handed and the idle eat.” ~ Mark Twain

What Twain had to say in his speech, “The Knights of Labor — The New Dynasty,”4 must have shocked most of the men. The salvation of the nation and the world, explained Twain, was the militant U.S. labor rights group, the Knights of Labor. The same organization that, at that very time, had initiated one of the most radical and disruptive national labor strikes in the history of the United States.

In his speech, Twain praised the Knights’ effort to remedy the perennial evil of working people's exploitation at the hands of the idle few. He began his speech by commenting on the nature of power. “Power, when lodged in the hands of man, means oppression—insures oppression: it means oppression always,” Twain wrote. “Who are the oppressed?,” he later asked rhetorically. “The many: The nations of the earth; the valuable personages; the workers; they that MAKE the bread that the soft-handed and the idle eat.” Anticipating the next question, Twain wrote, “Who are the oppressors? The few: the king, the capitalist, and a handful of other overseers and superintendents.”

According to Twain, the unfair “division of the spoil” of labor persisted through the “might” of law. Only the might of a unified working class could “uncreate it.” Workers would need to heed the Knights’ call to unite across different trades to form an unyielding block against their “oppressors.”

Twain lived during and commented on what later historians would describe as the “Gilded Age,” a period in American history marked by extreme wealth at the expense of workers condemned to poverty. Historians borrowed the term “Gilded” from Twain’s satirical novel The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today (1873). The novel lampooned America's cheap version of peak civilization which would have otherwise been called a “Golden Age.”

Share this piece with someone who hasn’t met the revolutionary Mark Twain.

The Gilded Age was not golden, it was bloody, an age of repression, violence, and unmitigated exploitation. Historian James Ciment wrote that it might have been “the most socially violent in the nation's history, with massacres of Indians in the West, lynchings of blacks in the south, and open warfare between labor and bosses along railroad lines and industrial districts throughout the nation.”5

Excised from public consciousness is the repression ordinary working people endured to secure paltry labor rights. “Arguably, the labor ‘wars’ of the late 19th century represented the most violent and sustained struggle between capital and labor in human history,” wrote Ciment. “No less than three national strikes and literally thousands of local ones left hundreds dead, thousands wounded, and millions of dollars in property destroyed.”

The Knights of Labor

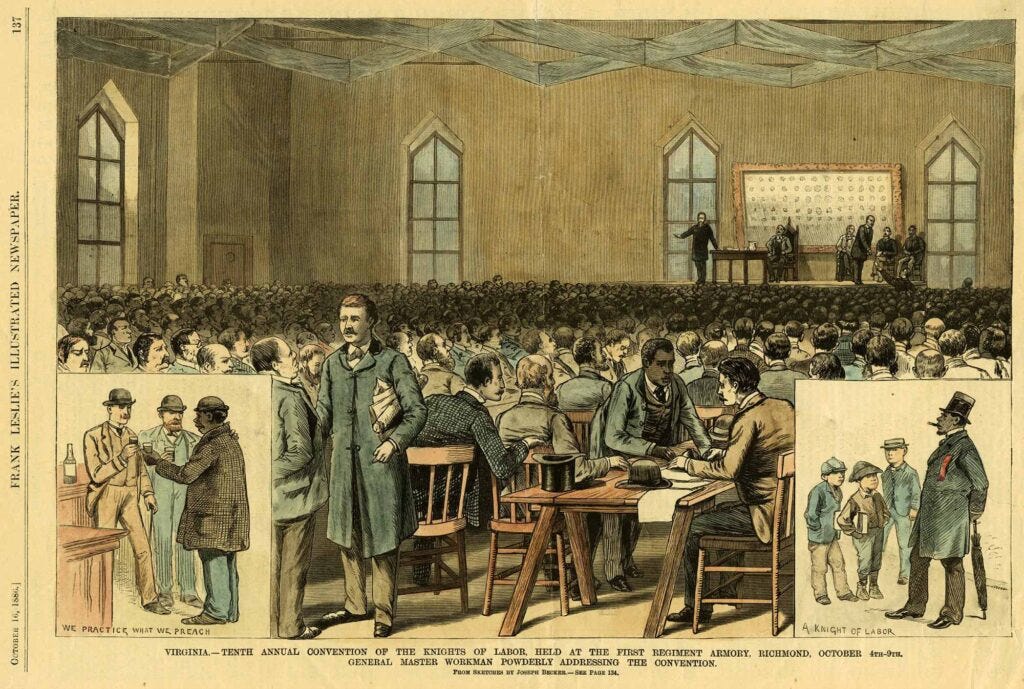

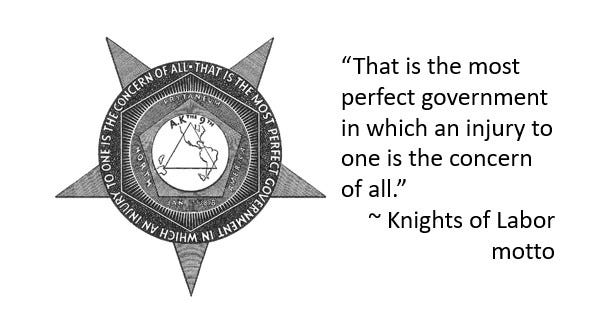

The Knights of Labor and the nascent American labor rights movement arose from these violent and volatile conditions. In 1869, a group of tailors met in secret in Philadelphia to create what would become the second national labor rights group in U.S. history.6 They chose a motto reflective of the imperfect7 inclusivity that would characterize their organization: “That is the most perfect government in which an injury to one is the concern of all.”

These words would later be resounded the following century by Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere,” King wrote from a Birmingham Jail. “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

At the height of its organizational development, the Knights of Labor had about 1 million members and thousands of chapters across the United States. Germans, Italians, Lithuanians, Frenchmen, Poles, Scandinavians, Hebrews, and Spanish speakers had chapters that were part of the larger organization.

See this interactive map of the Knights of Labor chapters across the nation.

Though not all local chapters adhered to the maxim, the national organization called for all to be paid “an equal price for equal labor, regardless of color, creed, country or sex.”8 At one point the organization had as many as 60,000 black members.9 Black chapters spanned the country from Helena, Montana to Newburyport, Massachusetts down to Leesburg, Florida.

In 1886, about 50,000 women were part of 192 women’s assemblies. As historian Howard Zinn explained, female textile workers and hat makers struck in 1884. The next year, New York cloak and shirt makers—men and women—went on strike. “The New York World called it ‘a revolt for bread and butter.’ they won higher wages and shorter hours.”

Women were not only members but also operators of chapters from San Francisco, California, and Denver, Colorado, to Galveston, Texas, and Albany, New York. Members included Irishwoman Leonora Barry, a “master workman” (president) of an assembly of 927 women. In a report for the Knights, Barry wrote that many working women had adapted to their oppressive labor conditions, acquiring “the habit of submission and acceptance without question of any terms offered them, with a pessimistic view of life in which they see no hope.” Barry and countless other women in the Knights of Labor worked tirelessly to combat that human-degrading oppression. In 1888, Barry reported visiting 100 cities and towns and distributing nearly 2,000 leaflets.

American Labor’s Anti-Capitalist Manifesto

The opening of the Knights' “Preamble and Declaration of Principles” read, “The alarming development and aggressiveness of the power of great capitalists and corporations under the present industrial system will inevitably lead to the pauperization and hopeless degradation of the toiling masses.” To avert this moral catastrophe, “unjust accumulation and this power for evil of aggregated wealth” must be stopped.

The group cited Genesis 3:19 as informing their objection to capitalist systems: “In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread.” Work and not mere ownership or inheritance, in other words, should determine our lot in life.

Published around 1878, the “Declaration of Principles” called all who embraced the maxim “the greatest good to the greatest number” to join them in seeking to “make industrial and moral worth, not wealth, the true standard of individual and national greatness.”

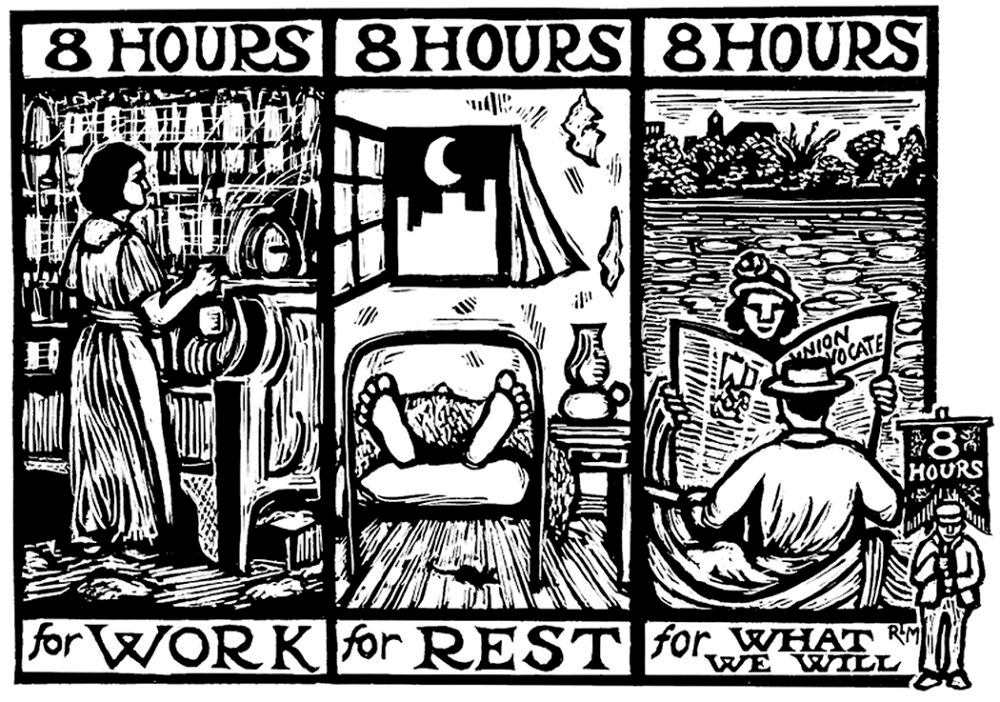

The organization’s overarching goal was to secure the right of workers to “sufficient leisure in which to develop their intellectual, moral and social faculties.” This goal required the government to enact safety standards for workers on the job, requirements that employers pay workers weekly, the prohibition of employing children under 15 years of age, an end to using prison labor, and protections for workers wishing to form unions. The Knights also sought equal rights for “both sexes,” a “graduated” or progressive income tax, and the use of technical gains to gradually reduce the workday to eight hours.

To secure genuine worker autonomy, the Knights called on the government to help establish worker cooperatives to facilitate the eventual overcoming of an exploitative “wage” system in which laborers were forced to rent themselves out for others’ profit.

In his Hartford speech, Mark Twain heaped praise on the Knight’s “Manifesto of demands.” Twain described the Knights’ pleas as “older than Scriptures” and “as old as Tyranny—old as Poverty—old as Despair.” The cry for human liberty and justice “is the oldest thing in this world—being as old as the human voice.” The reader of their manifesto, Twain wrote, was left asking,

“Is it possible that so plain and manifest a piece of justice as this, is actually lacking to these men, and must be asked for?—has been lacking to them for ages, and the world’s fortunate ones did not know it; or, knowing it could be indifferent to it, could endure the shame of it, the inhumanity of it?”

Addressing his elite audience, Twain said that the Knights’ demands “impeaches certain of us of high treason against the rightful sovereign of this world,” that is to say, against the workers and, therefore, makers of the world.

A Slavery of Wages

One reason for the tumult of the Gilded Age is that nineteenth-century laborers had not fully acclimated to renting themselves out to an employer. None other than former slave and pioneering black American intellectual, Frederick Douglass, argued that those forced to sustain themselves by wages participated in an oppressive relationship akin to slavery.

During a September 25, 1883 speech in Louisville, Kentucky,10 Douglass called on workers to unite against the injustice of laborer exploitation. “It is a great mistake for any class of laborers to isolate itself and thus weaken the bond of brotherhood between those on whom the burden and hardships of labor fell,” explained Douglass.

Workers were uniquely united in the understanding of scarcity and privation. While the wealthy “know nothing of the anxious care and pinching poverty of the laboring classes, may be indifferent to the appeal for justice at this point,” Douglass argued, “the laboring classes cannot afford to be indifferent.”

Drawing on direct knowledge of slavery, Douglass declared chattel slavery different only in “degrees” from wage slavery.

“Experience demonstrates that there may be a slavery of wages only a little less galling and crushing in its effects than chattel slavery, and that this slavery of wages must go down with the other.”

Douglass added that the power of the white employers over the formerly enslaved black workers was a “power of life and death,” the power to dictate “work for me on my own terms or starve.” Such an arrangement was “a source of crime” and “poverty.”

Agreeing with Twain and the wider labor rights movement, Douglass believed the right of all workers to “an honest day’s pay for an honest day’s work” would only come through the power of collective action. This belief moved Douglass to challenge labor organizations including the Knights of Labor to live up to their promises of a multiethnic movement for workers’ rights. Sadly, the Knights increasingly succumbed to white supremacist apologetics near the end of its institutional existence.11

“The alarming development and aggressiveness of great capitalists and corporations... will inevitably lead to the hopeless degradation of the toiling masses.” ~ The Knights of Labor

The Great Southwest Railroad Strike

Just weeks before Twain extolling the Knights before his elite friends and acquaintances, the organization launched the Great Southwest Railroad Strike. The strike involved more than 200,000 workers and stretched across railway lines in Illinois, Kansas, Arkansas, Missouri, and Texas. Workers targeted Jay Gould, one of most notorious “robber barons” of the Gilded Age, and his Pacific and Missouri Pacific railroads.

One year earlier, more than 100,000 workers won concessions from Gould in another strike action organized by the Knights. But railway workers continued to report mistreatment. One Arkansan reported being made to work thirteen hours and paid for just ten hours. Adding insult to injury, he received a pay cut in his daily wages, a drop from $1.50 to $1.25 (equivalent to less than $50, today).12 The Knights responded with a March 1st strike.

Railroad workers weren’t just exploited, they were at routine risk of injury and death. Whereas the 2023 U.S. worker fatality rate was 3.5 per 100,000,13 American railroad workers died at a rate of 267 per 100,000 in 1889.14 In 1888, 2,070 railway work-related deaths and another 20,148 injuries were documented.15 This was a time when the loss of a finger, at the time, was considered a “minor” injury.16 As many as 25,000 to 80,000 workers died of “industrial fatalities across the United States” between 1865 and 1919.17

During the 1886 strike tensions quickly escalated during as the company refused to meet workers’ demands for better wages and working conditions. Striking workers deployed a variety of methods including the sabotage of train engines and occupying repair buildings. A Kansas news dispatch reported,

“At 12:45 this morning the men on guard at the Missouri Pacific roundhouse were surprised by the appearance of 35 or 40 masked men. The guards were corralled in the oil room by a detachment of the visitors who stood guard with pistols…while the rest of them thoroughly disabled 12 locomotives which stood in the stalls.”

Two days before Twain delivered his exuberant endorsement of the Knights and unified labor, striking railway workers burned railroad bridges to push their employer toward compromise. Before the end of the month, the Knights’ executive leadership and Gould arrived at an agreement. But the peace would not hold.

Many members of the Knights resumed their strident strike campaign after Gould stipulated the railway would not hire workers accused of damaging company property. Federal and state governments took forceful action against the striking workers, invalidating the labor guarantees achieved between the Knights and the Missouri & Pacific railway in 1885. Courts issued injunctions against the Knights’ “direct actions” and also limited public assemblies.18 Meanwhile the states of Missouri and Texas used their state militias to quell the strike.

Why would Mark Twain endorse the Knights at such a time of norm-breaking upheaval? Twain believed dominant society normalized the violence and destruction perpetuated by those in power while decrying and clutching pearls when destruction was conducted by those without institutional power. If anything, Twain took a markedly pessimistic view of nonviolent social reform. In A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889), the protagonist declares,

“All gentle cant and philosophizing to the contrary notwithstanding, no people in this world ever did achieve freedom by goody-goody talk and moral suasion: it being immutable law that all revolutions that will succeed must ‘begin’ in blood, whatever may answer afterward. If history teaches anything, it teaches that.”

Some may dismiss such comments as mere fictional dialogue, but Twain’s comments in the March 22, 1886 talk in Hartford are just as stark. Imagining what would happen if the working masses did take power, Twain said that they, being “not better than the masters that went before” would also oppress.

“The only difference is, he will oppress the few, they oppressed the many; he will oppress the thousands, they oppressed the millions; but he will imprison nobody, he will massacre, burn, flay, torture, exile nobody, nor work any subject eighteen hours a day, nor starve his family. He will see to it that there is fair play, fair working hours, fair wages; and further than that, when his might has become securely massed and his authority recognized, he will not go, let us hope, and determine also to believe.”

Twain understood that his hope of a new “dynasty” of workers would not come easy or quickly. The state and the “capitalists,” as Twain called them, would not only forcefully put down the Great Southwest Railway Strike but also exercise its power over workers demanding an eight hour work day in Chicago.

Want to help Humanities in Revolt grow? Become a paid subscriber or leave a tip

Haymarket and The Birth of May Day

Twain’s hope for organized workers to take the mantle of power soon clashed with the authority and might of those presently in power. On May 1, 1886, workers held nationwide strikes for an eight-hour workday.19 Tens of thousands of workers from a range of labor groups marched through cities including Boston, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, St. Louis, and Chicago.

As many as 80,000 workers joined anarchist organizers Lucy and Albert Parsons in marching up Michigan Avenue. On the third day of protests, police opened fire into a crowd of striking workers and their supporters outside of the McCormick Reaper Works, which reopened with non-union labor. Police fire killed two workers. The anarchist August Spies responded by distributing a flyer calling workingmen “to arms,” and other labor leaders organized a mass meeting the next day at Haymarket Square.

The May 4th Haymarket meeting was peaceful and poorly attended. About 3,000 people showed up including the labor-friendly Chicago mayor, Carter Harrison. Later in the event, after the Mayor had left and with him all but 300 people, the pro-business police inspector, John Bonfield, sent nearly 200 officers to Haymarket Square to order the crowd to disperse. As the speaker, Samuel Fielden, insisted that the gathering was “peaceable” and then relented to the captain’s order, an unknown assailant launched dynamite at the officers.

For three minutes, officers fired indiscriminately into the gathered crowd. “The Haymarket was littered with bodies and the street pavement was turned red with blood,” explains historian Richard Schneirov.20 “It is estimated that the police killed seven or eight civilians in the crowd and wounded between thirty and forty others. There was little mention and no troubling by the press over these civilian casualties.” In total, sixty-six officers were injured and seven died. Officer Mathias Degan died from injuries sustained from the dynamite. Six sustained injuries from police bullets. Three of the deaths were attributed to friendly fire.21

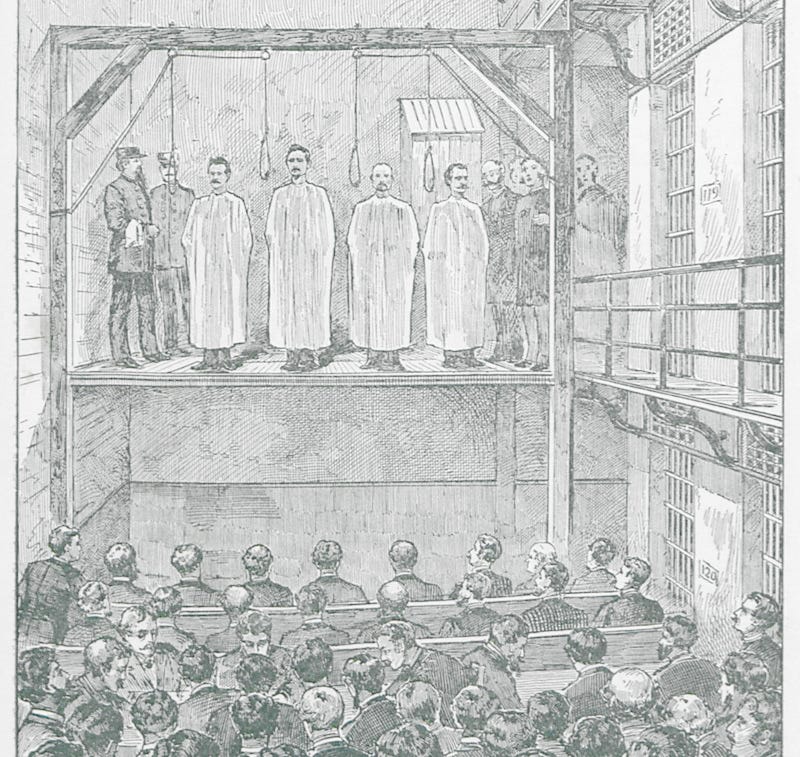

The state’s swift response resulted in a sham trial and execution of four men. On November 11, 1887, Albert Parsons, August Spies, George Engel, and Adolph Fischer embraced resolute demeanors and were hanged wearing white robes. Spies said, “The time will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today.”22

The labor movement would have the last word. On a day anarchists called “Black Friday,” 200,000 people lined the streets of downtown Chicago as the four men’s bodies were taken to Waldheim cemetery. Their public funeral was attended by 20,000 people, one of the largest in Chicago’s history.

After the trial, injunctions against labor organizing and leaders led some to conclude the Haymarket affair was a plot by business interests. Global outrage gathered against the killings of workers and persecution of labor leaders. Haymarket birthed International Workers Day—May 1st or May Day—and some of the Knights’ demands would later become law. It also seemed to prove Twain right—that chaos and pain were inherent to oppression and the struggle against it.

Twain’s Wish: That Workers Be Their Own Masters

In Twain’s 1886 address before the Knights, he said he often witnessed “a man abusing a horse” and wished he knew how to speak to the horse. Twain said he would have told the horse, “Fool, you are master here, if you but knew it. Launch out with your heels!” Twain said working people had long been brutalized like the horse. “The working millions, in all the ages, have been horses—were horses; all they needed was a capable leader to organize their strength and tell them how to use it, and they would in that moment be master.”

Twain had hoped the Knights of Labor, with their swelling ranks and growing impact, would help lead the exploited and oppressed to become their own masters. For when workers became “master” it would be “the only time in this world that ever the true king wore the purple; the only time in this world that ‘By the grace of God, King’ was ever uttered when it was not a lie.”

“When all the bricklayers, and all the machinists, and all the miners, and blacksmiths, and printers, and hod-carriers, and stevedores, and house-painters, and brakemen, and engineers, and conductors, and factory hands, and horse-car drivers, and all the shop-girls, and all the sewing-women, and all the telegraph operators; in a word all the myriads of toilers in whom is slumbering the reality of that thing which you call Power...when these rise, call the vast spectacle by any deluding name that will please your ear, but the fact remains a Nation has risen.”

Twain’s hopes for the ascending kingship of labor would be forestalled within months of his speech. The Knights’ 1886 strike ultimately ended in failure as Gould refused to meet strikers’ demands and workers were met with state militias along with forces from the private policing company, the Pinkertons.

The strike’s failure and subsequent infighting also initiated the dissolution of the Knights23 and its displacement by the American Federation of Labor (AFL). Whereas the Knights brought together laborers across all sectors of employment, the AFL centered on so-called “skilled” crafts, diluting the nascent multiethnic labor movement the Knights began.

Yet it would be unwise to presume history is written in simple causal patterns akin to lighting a fire that grows into an inferno of social transformation. The Knights of Labor and thinkers like Mark Twain lit a fire that quickly burned away. Yet embers remained. And those embers made it all the easier for those who came after to ignite the flames of social change.

In the wake of the Knights’ efforts, workers continued to become activated and organized. In Little Rock, Arkansas, black and white members of the Knights collaborated to support a black cotton pickers strike in July 1886.24 That same year, black and white laborers including members of the Knights formed the Union-Labor Party which challenged the white supremacist-aligned Democratic Party.25 Worker-centered third-party efforts would persist with presidential candidates Eugene V. Debs earning 6% of the vote in 1912 and Robert M. La Follette earning 16.6% of the vote in 1924.

Within just 60 years, a blink in human history, some of the core demands of the Knights were rendered into law through the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act. The legislation passed as part of the New Deal,26 establishing a minimum wage, a forty-hour work week, and regulated labor practices involving children.

Now as child labor laws are rolled back and union membership continues to decline, our task is to overcome fatalism and ignite the embers of possibility left by the Knights of Labor and others who came before and after them. The coals of workers’ rights may be dim but they are not dead, that is, not if we refuse to let them die.

❤️ Like to amplify hidden labor history🔄 Share with a fellow friend to workers💬 Comment your favorite Twain quote—or critique✊ Subscribe to Humanities in Revolt for more stories of visionary resistance

During a November 20, 1900 speech, Mark Twain defined a classic book as “something that everybody wants to have read and nobody wants to read.” (“The Disappearance of Literature.”)

“The radical of one century is the conservative of the next,” wrote Twain, in his notebook. “The radical invents the views. When he has worn them out the conservative adopts them.”

Mark Twain, “The New Dynasty,” March 22, 1886, in Mark Twain: Collected Tales, Sketches, Speeches, & Essays 1852–1890 (New York: Library of America, 1992), 883–890

Harold K. Bush, Mark Twain and the Spiritual Crisis of His Age (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2007), 116.

James Ciment, “The Gilded Age, 1877–1896,” in The Encyclopedia of Third Parties in America, vol. 1, ed. Immanuel Ness and James Ciment (Armonk, NY: Sharpe Reference, 2000), 29–36.

The first national labor group in the United States was the National Labor Union, founded on August 20, 1866.

The Knights of Labor was not immune from racism or xenophobia. Western chapters of the group were particularly discriminatory toward Asian people, endorsing the Chinese Exclusion Act. In the South, some chapters embraced racist attitudes toward the inclusion of black laborers and even sabotaged their organizing efforts.

The statement, “The working people must unite and organize, irrespective of creed, color, or nationality,” was also affirmed in the Proceedings of the General Assembly of the Knights of Labor, Fourth Regular Session, Held at Philadelphia, Pa., September 1884 (Philadelphia: Journal of United Labor, 1884), 715.

Philip S. Foner, Organized Labor and the Black Worker: 1619–1981. New York: International Publishers, 1981., 48

Frederick Douglass, Address of Hon. Fred. Douglass, Delivered Before the National Convention of Colored Men, at Louisville, Ky., September 24, 1883 (Louisville, KY: Bradley & Gilbert, 1883)

Philip S. Foner, Organized Labor and the Black Worker: 1619–1981. New York: International Publishers, 1981., 63

Theresa A. Case. “Great Southwestern Strike.” Encyclopedia of Arkansas. June 16, 2023.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, National Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries in 2023 (Washington, DC: BLS, 2024)

The figures provided are 2.67 per 1,000 for “American Railroad workers.” The 267 figure results from multiplying 1,000 by 100. Also note that “American trainmen” died at a rate of 852 per 100,000. Trainmen were “guards, brakemen, and shunters.” Mark Aldrich, “History of Workplace Safety in the United States, 1880–1970,” EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples, August 15, 2010.

Carroll W. Doten, “Recent Railway Accidents in the United States,” Publications of the American Statistical Association 9, no. 69 (March 1905): 158, table 1

Mark Aldrich, Death Rode the Rails: American Railroad Accidents and Safety, 1828–1965 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006), 104.

Another 300,000 to 1.6 million workers sustained serious injuries on the job. Newspapers of the period such as Chicago Tribune compared the scale of death and injury from industrial work to that of the Civil War. Michael K. Rosenow, Death and Dying in the Working Class, 1865–1920 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2015), 8.

Case. “Great Southwestern Strike.”

The effort was initiated by the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions, later named the American Federation of Labor (AFL)

For a detailed and illuminating account for both the Haymarket Affair and the social-political context in which it occurred see Richard Schneirov, “The Haymarket Bomb in Historical Context,” Illinois During the Gilded Age, Digital Library of Northern Illinois University.

“A telephone pole removed from the scene, probably at the behest of the police,” wrote Schneirov, “was filled with bullets all coming from the direction of the police.”

Parson's final words were, “Let the voice of the people be heard!” Fischer's final words: “This is the happiest moment of my life.” Engels declared, “Hurrah for anarchy.” Eight anarchists were eventually put on trial that would later be roundly condemned as prejudicial. None of the jurors were wage earners, and all indicated they could not fairly decide on the case. Nevertheless, one man was sentenced to 15 years of hard labor and seven of the men were sentenced to death. One of the men, Louis Lingg, died by suicide in his cell. Two of those condemned to death and the man condemned to hard labor were eventually pardoned in 1893.

In an 1895 interview, Twain admitted the failings of the Knights of Labor's leadership but praised the plan of, as the interviewer explained, "consolidating all classes of workers into one body for mutual help in the effort to redress grievances.” "Mark Twain: A Talk with the Famous Humorist," Lyttelton Times (Christchurch, N.Z.), November 13, 1895, 5–6; in Mark Twain: The Complete Interviews, ed. Gary Scharnhorst (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006), 249-251.

Case. “Great Southwestern Strike.”

Matthew Hild, “The 19th Century Labor Movement That Brought Black and White Arkansans Together,” Zócalo Public Square, February 28, 2019

Twain’s words not only helped to name the problem of economic injustice but also to brand the solution. When Franklin Delano Roosevelt named his social reforms part of a larger “New Deal,” he was referring to Twain’s book, A Connecticut Yankee

in King Arthur's Court (1889). The story's protagonist, Hank Morgan, calls for a "New Deal" for the economically exploited and looks forward to a future when workers are empowered.

Wow - incredible academic essay Jeffery - with footnotes etc! Love Samuel Clemens aka Mark Twain - on eo f America's first popular progressives. Three things - have you ever his short story, Mysterious Stranger? Profound story about how the devil incarnates to f' and twist people everywhere all the time! Have you read James by Percival Everette? Great version of Huck Finn story yet via slave perspective. And have you seen the recent Kennedy Center Twain prize for Conan O'Brian? On Netflix and worth watching for laughs and his speech about Twain and state of America at the end.

Very good piece!