Imperialism and American Privilege, Those Which Must Be Named

Part V of a series exploring the intersection of movies, popular culture, and the U.S. military

As with Hollywood representations, the dominant political discourse on U.S. foreign policy omits and invisibilizes our nation’s often brutal military history. During his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, December 10, 2009, President Barack Obama said,

“Whatever mistakes we have made, the plain fact is this: The United States of America has helped underwrite global security for more than six decades with the blood of our citizens and the strength of our arms…. America has never fought a war against a democracy, and our closest friends are governments that protect the rights of their citizens.”

Such statements ignore altogether the realities like the U.S. subversion of democracy in countries such as Chile.

Acknowledgment of the violent and destructive nature of many of our government’s foreign policy decisions is rare. During his tenure as Secretary of State, Colin L. Powell admitted, on February 20, 2003, U.S. involvement in toppling Chilean democracy in the 1970s, acknowledging it “is not a part of American history that we're proud of. We now have a more accountable way of handling such matters and we have worked with Chile to help it put in place a responsible democracy.”

Even muted criticisms like Powell’s remarks are difficult to contextualize within dominant cultural narratives. Most of the public has nothing to secure these ideas to. They are discordant, almost incomprehensible noises amounting to little more than “we’re not perfect.” This is because they run so counter to the prevailing narrative typified by Obama's characterization of American exceptionalism. The inconsistency of such critiques is further evidenced by the fact that Powell participated in the Bush administration’s destructive invasion of Iraq less than one month after making his statement on Chile.

In an interview with documentarian, John Pilger, CIA operative, Duane R. “Dewey” Clarridge, offered an even rarer, unvarnished take on the scope and prerogative of U.S. military power. Carriage, who was chief of the CIA's Latin American division from 1981 to 1987, openly admitted that the U.S. has used violent intervention to overthrow governments it does not favor.

“We will intervene whenever we decide it is in our national security interest to intervene. And if you don't like it, lump it. Get used to it, world.”

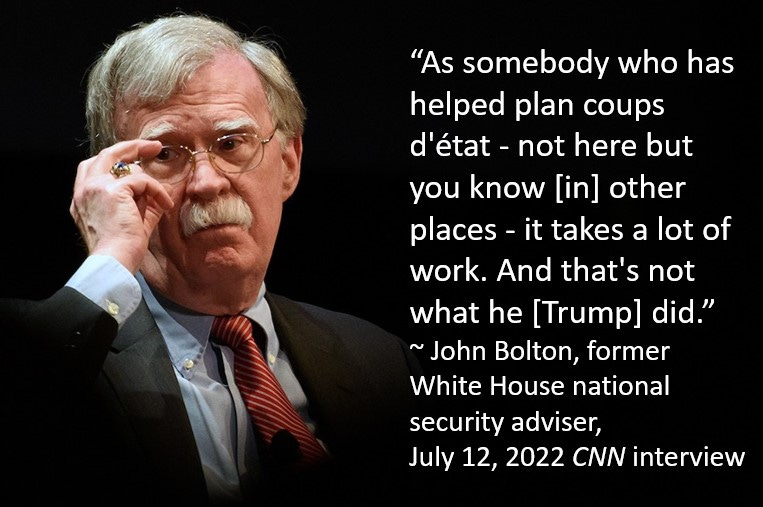

In 2022, former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations and former White House national security adviser, John Bolton flippantly admitted to having a role in helping overthrow foreign governments for the U.S. government. Criticizing President Donald Trump’s failed attempt to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election, John Bolton said,

“As somebody who has helped plan coups d'état—not here but you know [in] other places—it takes a lot of work. And that's not what [Trump] did.”

In early December 2022, Bolton expressed outrage over former President Trump's social media statement that “the termination of all rules, regulations, and articles, even those found in the Constitution” might be necessary to address the 2020 election results, which he claimed were inaccurate. Bolton said he was considering a run for the Republican presidential nomination, against Trump, because of the former president’s lack of respect for the Constitution. A clear example of “American Exceptionalism,” Bolton views U.S. democracy as sacred, but the democracy and constitutional order of other nations as expendable depending on their service to (elite) political interests.

See appendix II in William Blum’s book, Killing Hope: U.S. Military & CIA Interventions since World War II, for a comprehensive list of U.S. military interventions, abroad, between 1798 and 1945.

Unbeknownst to most Americans, we benefit from a cultural privileging of our national-ethnic identity. Even if we are lower-income or subject to other forms of discrimination within the U.S., American citizens retain a privileged position in the global political order compared to members of other nations which would be treated as belligerent, criminal, or undemocratic for adopting foreign policy and military tactics frequently accepted or even celebrated by our nation. The often misunderstood concept of intersectionality is useful in fully grasping this often overlooked advantage.

Intersectionality and American Privilege

Intersectionality, the innovation of black feminist thinkers, challenges us to recognize the multifaceted nature of human identity, and how power and privilege are distributed in dynamic and complex ways. The aim of intersectionality, as an idea and insight, is to challenge reductionist thinking about power and privilege.

Intersectionality encourages intellectual nimbleness and contextual analysis in place of dogmatic, concretized thinking. Rather than viewing human injustice or oppression as a hierarchically ordered tower where we are either up or down, intersectionality understands oppression as a complex web of relations—a “matrix” as sociologist Patricia Hill Collins describes it.

Intersectionality helps us recognize that privilege and oppression are not permanently and statically tied to singular categories of human identity. Oppression/privilege can be compounded or reduced depending upon the dynamic and fluctuating cultural context of our social identity. The privilege/disadvantage that we might experience as men or women can change when another aspect of our identity is culturally significant within a given social context, such as being rich or poor. As Collins explains in Black Feminist Thought (1990),

“Intersectionality refers to particular forms of intersecting oppressions, for example, intersections of race and gender, or of sexuality and nation. Intersectional paradigms remind us that oppression cannot be reduced to one fundamental type, and that oppressions work together in producing injustice.”

Even when one aspect of our identity is culturally-socially privileged over another—for example, a man treated with greater respect than his female co-worker in their finance job—it is vital to recognize that our life and experience is not determined by a single feature of our social identity. There are many different kinds of men and women just as there are different kinds of black and white people or different kinds of citizens of the United States.

An American man living in poverty, for example, who lacks the access to basic healthcare services necessary for extending his life is less privileged, in at least this area of life, compared to a woman of upper middle class means with adequate access to healthcare. Intersectionality reminds us, however, that the comparatively privileged woman and disadvantaged man may find their privilege and disadvantage altered or even reversed in a different social context or circumstance, such as when they leave the medical facility and enter a different domain of ordinary life where, for example, the woman is subjected to sexual harassment.

Read the first four parts of the series exploring warfare and popular culture: (I) Giving Veterans More than "Thanks,” (II) Going to the Movies...with the Pentagon, and (III) The Top Gun Effect: Why Hollywood Movies Matter to the U.S. Military, (IV) The Other 9/11: Movies, Militarism, and What's Missing from Popular American Consciousness

Those of us who are “American” have a particular social identity that gives us some unrecognized privilege over others around the world, privilege that become clear the more we learn about our nation’s involvement in the political-economic-social affairs of other nations. (It’s worth noting that we may also have some unrecognized disadvantages, such as less vacation time, student debt, and higher costs for vital medicines, when compared to other wealthy industrial nations.)

Few Americans recognize that they possess the unique, unearned privilege of belonging to a nation that routinely uses its considerable political and economic might to insist other nations adopt, or adapt to, their strategic interests, values, and actions. Pentagon-backed blockbuster Hollywood movies, for example, do not ask us to imagine ourselves into the position of people of other nations. We are not asked how we might feel if a foreign nation installed a military base in our city or state. Rather, such films help hide an otherwise overt nationalism which presumes that we are entitled to do what others are obviously not permitted to do.

We are made to feel that is not only normal but generous to install military units and bases in other nations. Our military is heroic and virtuous, functioning as global defenders of freedom and democracy. Indeed, very few Americans know the often bloody and aggressive details of their nation’s foreign policy history. This fact itself is indicative of the unique privilege Americans experience as those living in the greatest military super-power in human history: we are able to live out our lives without any serious need to know what our government does in our name.

For most Americans, it is simply an unthinkable piece of common sense that it would be absolutely unacceptable for our nation to host a foreign nation’s military base. Yet it is simultaneously taken for granted that our nation’s military spans the globe. Even if we do not know that the number of bases approximates 800 in more than 70 countries, it hardly crosses our mind to imagine ourselves into the position of other nations hosting a foreign power’s military. Such a blind-spot exemplifies the ubiquitous though rarely acknowledged ethnocentric bias of being a citizen of the world’s greatest military superpower.

Those living on the other side of our decisions are acutely aware of our government’s “interventions.” This was evidenced after I published an article on the “other 9/11,” the U.S. supported coup in Chile on September 11, 1973. Many Chileans commented that they vividly recalled clandestinely viewing the 1982 film, Missing, which documented the disappearance of a U.S. journalist during the opening days of the coup.” One comment typifying the others read, “This movie was absolutely forbidden in Chile while it was being show elsewhere. Many Chileans, including myself, managed to get the film by any means.”

A further example of the blind-spots that accompany American privilege is the rather flippant way in which many are able to overlook the lethal decision making of towering figures in mainstream American politics. Former president George Bush is still invited to pontificate about global affairs even as he led the U.S. to invade Iraq for Weapons of Mass Destruction that did not exist. Hundreds of thousands of Iraqis died as a result. Meanwhile, the current president of the United States, Joe Biden, was a chief advocate of the Iraq War, a well-documented fact that is often willfully ignored.

In contemporary politics such lethal errors of judgment are set aside as good-faith mistakes or culturally “forgotten” all together. Those skeptical of the privilege that comes with the social status of being “American” should contemplate this question: can we seriously imagine the U.S. government or public tolerating the rehabilitation of a foreign leader, responsible for an “intervention” that resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Americans and the destruction of our basic social infrastructure? The very fact that the euphemistic term “intervention” is routinely used in American discourse to describe covert and overt military campaigns that destabilize entire nations exemplifies the overlooked privilege that accompanies American identity.

Imperialism: that which shall not be named

Our popular culture does not dare to discuss the meaning and significance of imperialism as it pertains to the United States. Few in mainstream media speak about empire the way that Andrew Carnegie and Mark Twain did. Though the first is known as an important captain of industry and wealthy philanthropist and the second a great American writer, few know that both were united as ardent supporters of the Anti-Imperialist League. The group formed in 1898 to stop the U.S.'s annexation of the Philippines.

While we are taught that important figures in U.S. history such as Booker T. Washington and Ida B. Wells fought against racism, we do not learn that they argued there was an inextricable link between militarism and racism. Both spoke out against U.S. expansionism during the Spanish-American War.

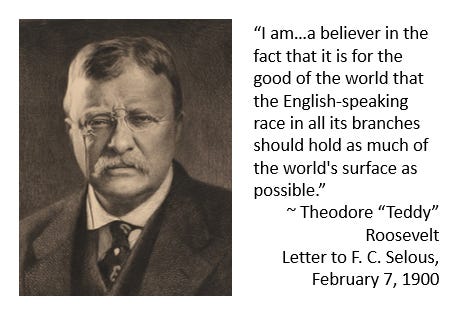

We no longer speak of empire in the explicit terms that advocates of U.S. imperialism like Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt did. Roosevelt not only openly invited war as a character and “race” building experience, he explicitly stated his belief in the superiority of the “English-speaking race.” In a February 7, 1900 letter to a friend, Roosevelt wrote that he was

"a believer in the fact that it is for the good of the world that the English-speaking race in all its branches should hold as much of the world's surface as possible.”

In a January 14, 1898 letter, Roosevelt wrote he was “a good deal disheartened at the queer lack of imperial instinct that our people show.” If Americans failed to embrace the imperialist ethos, Roosevelt feared “it will show that we either have lost, or else wholly lack, the masterful impulse which alone can make a race great.”

Pioneering American novelist and commentator, Mark Twain, by contrast, wrote about a different kind of disappointment in America. He spoke frankly about the moral duplicity and contradictions of imperialists like Roosevelt. Twain called attention to their lack of ethical consistency as they claimed Christianity as the moral backbone of their militaristic campaigns. “As Christ died to make men holy,” Twain wrote in “Battle Hymn of the Republic (Brought Down to Date),” “let men die to make us rich—Our god is marching on.”

Though he is widely respected as a great American author, few know that Twain a leading figure in the movement against U.S. empire building. Twain served as the American Anti-imperialist League's vice president from 1901 until his death in 1910.

In “The War Prayer” (1905), Twain presents a preacher frenzied with nationalism and clamoring for war. “Bless our arms,” he proclaims from the pulpit, “grant us the victory, O Lord our God, Father and Protector of our land and flag!” The preacher is then interrupted by a stranger who claims to bring a message from God. The man cautions the congregation to recognize the profane logical implications of their prayers for victory. He then articulates the unspoken but inextricable implication of their prayer. To pray for victory on the battlefield is to ask God to

“help us to tear their soldiers to bloody shreds with our shells; help us to cover their smiling fields with the pale forms of their patriot dead; help us to drown the thunder of the guns with the shrieks of their wounded, writhing in pain; help us to lay waste their humble homes with a hurricane of fire; help us to wring the hearts of their unoffending widows and unavailing grief; help us to turn them out roofless with their little children to wander unfriended the wastes of their desolated land in rags and hunger and thirst, sport of the sun-flames of summer and the icy winds of winter, broken in spirit, worn with travail, imploring Thee for the refuge of the grave and denied it—for our sakes who adore Thee, Lord, blast their hopes, blight their lives, protract their bitter pilgrimage, make heavy their steps, water their way with their tears, stain the white snow with the blood of their wounded feet! We ask it, in the spirit of love, of Him Who is the Source of Love, and Who is the ever-faithful refuge and friend of all that are sore beset and seek His aid with humble and contrite hearts. Amen.’”

After the man who delivered this prophetic warning left, the congregation determined that he “was a lunatic because there was no sense in what he said.” Here Twain revealed the ignorance of those blinded by nationalist-ethnocentric bias. They could not even fathom how rooting for the military victory of their government and fellow citizens at the expense of the lives of a foreign people violated the Christian ethical obligation to “love” all people as though they were “brothers,” including their enemies. Such is the blinding power of dogmatic nationalism.

Twain wrote with sardonic disgust of the U.S.’s betrayal of Filipino independence following our unified efforts to defeat Spain in 1898. In “To the Person Sitting in Darkness” (1901), Twain wrote that the people of the Philippines were left to interrogate American mendacity:

“There must be two Americas: one that sets the captive free, and one that takes a once-captive's new freedom away from him, and picks a quarrel with him with nothing to found it on; then kills him to get his land.”

Pro-imperialist American leaders brought the U.S. into open warfare with the same Filipinos we had allied ourselves with against the Spanish empire and promised to liberate. The U.S. military utilized a variety of tactics to subdue Filipino resistance including the “water cure” torture, destroying homes, and cutting off food supply. The U.S. military also ordered massacres.

In March 1906, U.S. forces used machine guns to kill between 800 and 1,000 of the Moro people, a majority Muslim ethnic group in the Philippines. The Moros sought refuge from U.S. occupation in a remote, extinct volcanic crater called Bud Bajo. The attack came to be known as the “Moro Crater Massacre.” It was ordered by major general Leonard Wood who had helped Theodore Roosevelt organize the “Rough Riders,” a volunteer cavalry regiment, during the Spanish-American War. While fewer than 25 U.S. soldiers died, just six of the hundreds of Moro people are believed to have survived the onslaught.

Following the “victory,” President Roosevelt issued a statement congratulating Wood and his men for their “brilliant feat of arms wherein you and they so well upheld the honor of the American flag.” Twain responded in characteristic fashion by ridiculing the venerability of the “battle.”

“General Wood was present and looking on. His order had been, ‘Kill or capture those savages.’ Apparently our little army considered that the ‘or’ left them authorized to kill or capture according to taste, and that their taste had remained what it has been for eight years, in our army out there—the taste of Christian butchers.”

A few years earlier, Americans were given a unique glimpse into military leadership’s mentality when Marine Major Littleton Waller testified that Army General Jacob H. Smith ordered him to launch an attack to kill all persons over the age of 10 on the island of Samar. Waller recounted Smith telling him,

“I want no prisoners. I wish you to kill and burn, the more you kill and burn the better it will please me. I want all persons killed who are capable of bearing arms in actual hostilities against the United States.”

When Waller asked for a specific age limit, Smith stated that everyone over the age of 10 was to be killed. The subsequent death toll is put around 2,000.

Rank-and-file soldiers told similar stories of indiscriminate killing in their private letters.1 Anthony Michea of the Third Artillery described the carnage he participated in upon launching an attack in Malabon. “… we went in and killed every native we met, men, women, and children. It was a dreadful sight, the killing of the poor creatures. The natives captured some of the Americans and literally hacked them to pieces, so we got orders to spare no one.” By 1902, the U.S. military had killed as many as 200,000 civilians in the Philippines. More Filipinos died fighting the U.S. in three-and-a-half years than had died in 300 years of Spanish rule.

Horrors Hidden in Plain Sight

These facts are disappeared into obscure academic texts or retrospective documentaries distilled of contemporary ethical and political significance. That what we call the United States is a land braided together with wars of conquest—”expansion” and “annexation”—is a fact that glosses over the mind as though one were describing some distant and irrelevant reality with no tangible meaning. That our nation is connected to empire is either an obvious truth that merits exactly no discussion whatsoever, or blatantly blasphemous, a slanderous accusation against the freedom-loving character of the United States. The second reaction is contradicted by the readily available evidence. We need only open Stephen Kinzer’s The True Flag: Theodore Roosevelt, Mark Twain, and the Birth of American Empire (2017) to gain much needed perspective. (Audiobook here.)

We can only wonder how the world or at least the U.S. might be different if our most entertaining and heroic movies gave us not only the Mavericks and conventional war heroes, but also gave voice to figures like the two-time medal of honor recipient, Major General, Smedley D. Butler of the U.S. Marines.

Butler fought in the Philippine-American War Butler and participated in U.S. military "policing" interventions in Central America and the Caribbean, from Honduras, Nicaragua, to Haiti, called "Banana wars" conducted on behalf of U.S. commercial interests including those of the United Fruit Company.

Butler gave countless speeches on the way his services had been used for economic racketeering on behalf of the wealthy in the U.S. In his book, War is a Racket (1935), Butler wrote:

"War is a racket. It always has been. It is possibly the oldest, easily the most profitable, surely the most vicious. It is the only one international in scope. It is the only one in which the profits are reckoned in dollars and the losses in lives. A racket is best described, I believe, as something that is not what it seems to the majority of the people. Only a small 'inside' group knows what it is about. It is conducted for the benefit of the very few, at the expense of the very many. Out of war a few people make huge fortunes."

One imagines that the Pentagon’s entertainment office might refuse to support a major motion picture representing this vision of the military, despite its originating in one of the most well-respected and highly decorated military men in our nation’s history.

Naming Nationalistic Bias

If we are committed to honoring human dignity and combatting oppression in all of its forms, we must learn to recognize the injustices concealed by cultural-ideological biases. Biases that we have long internalized, blinding us to the undue privilege we reap from unjust social structures we ostensibly object to. Building on the insights of previous thinkers including Erich Fromm, Paulo Freire, and Audre Lorde, Collins notes we have a tendency to identify particular forms of oppression as most important at the expense of recognizing other, intersecting oppressions.

“In essence, each group identifies the oppression with which it feels most comfortable as being fundamental and classifies all others as being of lesser importance. Oppression is filled with such contradictions because these approaches fail to recognize that a matrix of domination contains few pure victims or oppressors. Each individual derives varying amounts of penalty and privilege from the multiple systems of oppression which frame everyone’s lives.”

Those committed to combatting oppression must do more than comprehend their unique disadvantage in relation to a single element of injustice. They must also learn to recognize their participation, however unconscious and unintended, in political structures and systems of thought that uphold and regenerate injustice. Collins writes:

“Once we realize that there are few pure victims or oppressors, and that each one of us derives varying amounts of penalty and privilege from the multiple systems of oppression that frame our lives, then we will be in a position to see the need for new ways of thought and action.”

Recognizing the privilege those of us living in the U.S. experience just by virtue of being citizens of the world’s chief superpower with unparalleled military might and influence allows us to move closer toward the goal of combatting injustice in all of its manifestations.

Such awareness also allows us to begin seeing the self-destructive consequences of that privilege born by those of us outside of elite social status. For as Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. made clear, time and time again, money spent on unnecessary warfare abroad was funded by and at the expense of the exploited at home. In his April 4, 1967 speech, “Beyond Vietnam,” King observed, “A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death.” The solution for all, he argued, was to drop the prideful vanity of nationalism along with racism and religious-based discrimination in favor of worldwide fellowship; love, in a word. Because love and respect for human dignity renders unjust privilege impossible, humanizing the oppressed and the oppressor, allowing them to recognize the interconnectivity of their lives.

If you enjoyed this post please share it with others and like it by clicking the heart icon. Be sure to subscribe if you haven’t already.

Invite Dr. Nall to Speak

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook or by leaving a comment.

Several letters were published by the Anti-imperialist League, in an 1899, as pamphlet titled “Soldiers Letters.”