Getting Greenland: The Historical Context for Trump’s Ambitions for Greenland, Gaza, and Beyond

Or Sharpening the Eagle's Talons: Why We Should Take Trump's Imperial Rhetoric Seriously

During the Joint Address to Congress, President Donald Trump stated, “One way or the other we're going to get it.” The President was referring to Greenland, an autonomous territory of Denmark.

Trump spoke of getting Greenland with a smile, lending to the belief of some that President’s bellicose rhetoric is simply a negotiating tactic. But the ominous historical context informing Trump's comments demand to be taken seriously.

Earlier in the historically lengthy speech, Trump listed changing the name of Alaska’s Mount Denali to “Mount McKinley” as one of his administration’s early accomplishments. At the start of his presidency, Trump issued an executive order changing the mountain’s name from Denali to McKinley. The change was meant to honor “a great president, William McKinley,” explained Trump.

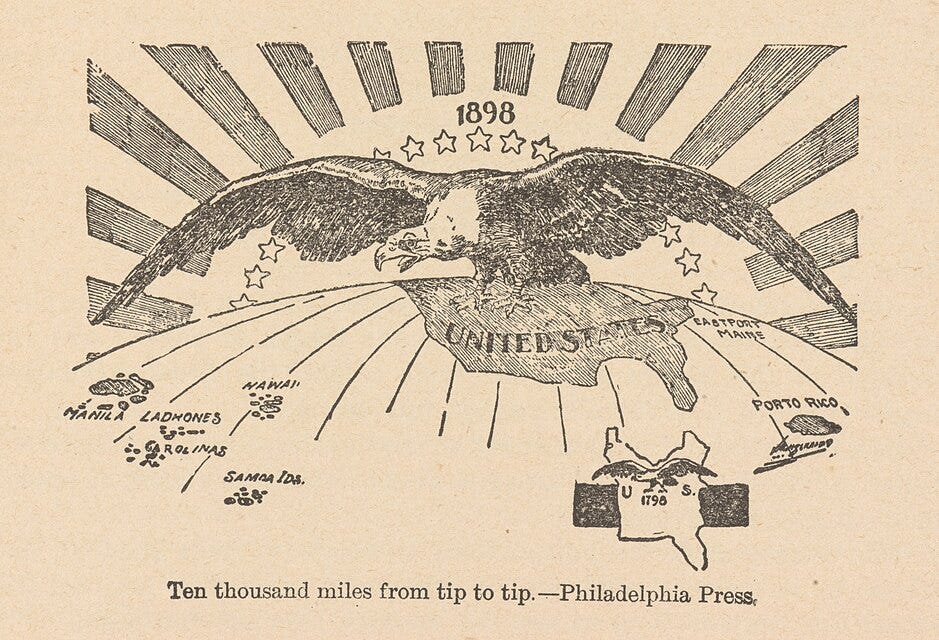

Trump’s decision to honor McKinley, recognizing the former president’s role in the Spanish-American War, a forthright imperialist endeavor, along with his insistence on “getting” Greenland, “reclaiming” the Panama Canal, “owning” Gaza, and incorporating Canada into the United States give good reason for fearing Trump may have imperial ambitions of his own.

At a minimum, the President's rhetoric presents a unique opportunity to rekindle open and honest public discourse about the obscured history of American imperialism and the effects endured by its victims. Trump’s braggadocio presents an opportunity to look honestly upon the soul of our nation and contemplate its rehabilitation or transformative rebirth.

Mount McKinley, Ascending U.S. Imperialism

In 1896, a gold prospector dubbed North America’s tallest mountain “Mount McKinley” in honor of the President. Notably, McKinley was a native of Ohio who never traveled to Alaska. Nevertheless, in 1917, the federal government honored the President, who was assassinated on September 14, 1901, by officially giving the mountain his last name. The decision to supplant “Denali,” the name long used by Indigenous peoples with a deep connection to the land, with “McKinley” exemplified his legacy as a leading figure in U.S. imperialism.

On the first day of his second administration, January 20, 2025, President Trump issued an executive order restoring “the name of a great president, William McKinley, to Mount McKinley, where it should be and where it belongs.” The order specified President McKinley's accomplishments as having “heroically led our nation to victory in the Spanish-American War.” The decision came ten years after the Obama administration assented to requests of Alaskans to acknowledge the mountain’s traditional name.

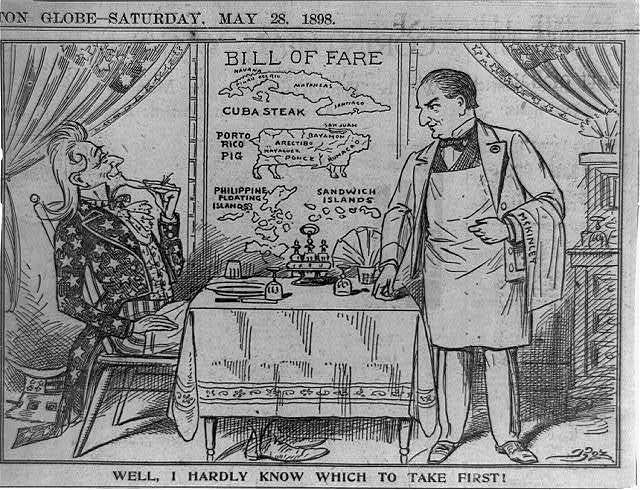

Behind what could be seen as a petty political naming battle is a potential reinvigoration of overt American imperialism. Trump’s reference to the Spanish-American War is particularly significant. Like Trump, McKinley did not campaign on U.S. expansionism. Yet McKinley initiated overseas empire-building the likes of which had never been seen from an American president. In fact, McKinley initiated what may have been the first U.S. military action rationalized as “humanitarian intervention.”

The United States entered the Spanish-American War ostensibly to support the Cuban revolutionaries fighting for the independence of their island. But by the time the Spanish were defeated, the U.S. decided that the Cuban people could not be trusted with self-rule. An American General named Shafter said the Cubans were “no more fit for self-government than gunpowder is for hell.” Attorney General John Griggs announced that the U.S. Army in Havana was an “invading army that would carry with it American sovereignty wherever it went.”

McKinley’s war with Spain ended with a December 10, 1898 treaty. Spain relinquished control of Cuba, paving the way for the United States to claim the territory. Spain further ceded control of Puerto Rico and Guam to the U.S. In exchange for a $20 million payment to Spain, the U.S. also received the 7,000 Islands of the Philippines. These decisions were made the same way the U.S. federal government named Alaska’s Mount Denali “Mount McKinley,” independent of and in flagrant opposition to the will of the people of those lands including the 7 million residents of the Philippines.

From 1899 through 1902, the United States sacrificed 4,200 of its soldiers to subvert Filipino independence. The greatest losses were on the side of the Filipino people. The U.S. war caused the deaths of 20,000 independence fighters and as many as 200,000 civilians. This is to say nothing of the various forms of terror used to subdue Filipino resistance.

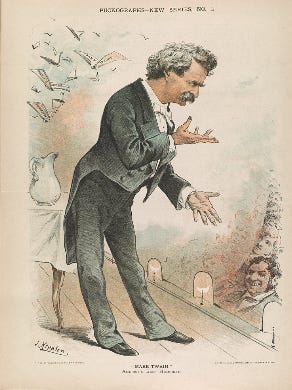

Famed satirist and author, Mark Twain, admitted initially embracing imperialist passions. “I wanted the American eagle to go screaming into the Pacific. It seemed tiresome and tame for it to content itself with the Rockies. Why not spread its wings over the Philippines, I asked myself? And I thought it would be a real good thing to do.” After overseas travel and reflection, and examining the Treaty of Paris, Twain wrote that he became an “anti-imperialist.”

“I am opposed to having the eagle put its talons on any other land.”

Addressing the United States’ treatment of the Cubans, Twain wrote,

“Training made us nobly anxious to free Cuba; training made us give her a noble promise; training has enabled us to take it back. Long training made us revolt at the idea of wantonly taking any weak nation's country and liberties away from it, a short training has made us glad to do it, and proud of having done it.”

Today, Twain is remembered as a great literary talent, responsible for authoring timeless works such as Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884). But his fervent opposition to U.S. empire, including his participation in the Anti-Imperialist League goes largely unacknowledged. Twain’s criticism of McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt’s imperial policies are obscured much the same way the very location of the United States is.

Where is the United States of America? Imperialism’s Surprising Answer

Americans are not only unaware of the origin of our nation’s composition, they are also often confused about where the United States is. Growing up in Miami, Florida in the 1990s, I recall occasions in which people complained about Puerto Ricans proudly flying the flag of Puerto Rico. Those discomforted by such displays would say things like, “Go back to your own country.” Apparently they were unaware of the fact Puerto Rico has been part of the United States of America since 1898.

Many Americans mistakenly conceive of the United States as a nation comprising 50 states. Few think to include the “territories” the United States has taken. Nearly 4 million people live in U.S. territories include American Samoa, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.1 Residents of all the territories with the exception of America Samoa are considered citizens. One limit on their citizenship—one Greenlanders ought to note —is none are permitted to vote in presidential elections.

Territorial acquisition under the McKinley administration was strictly motivated by U.S. strategic and economic interest, not the interests of the people of those lands. However, the risks associated with U.S. use of those lands often fell squarely on those same people. The case of Hawaii makes that clear.

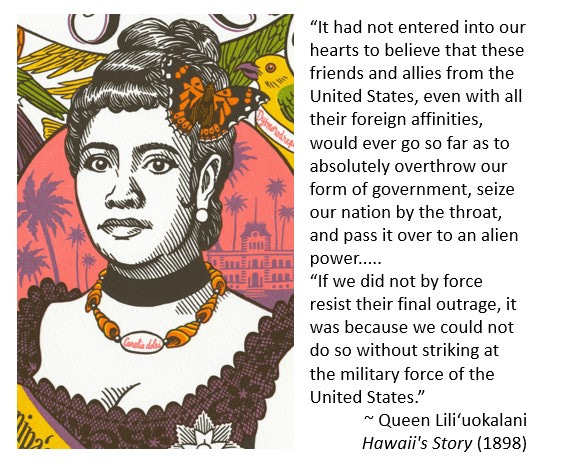

On January 17, 1893, American businessman, Lorrin Thurston and a group of 30 business leaders living in Hawaii staged a coup against Queen Liliʻuokalani of the Kingdom of Hawaii. The Queen observed the coup attempt “would not have lasted an hour” without the help of the U.S. military. Queen Liliʻuokalani had sought to change her kingdom’s constitution to reduce the political power of non-Hawaiians who were interfering in domestic political affairs. Seeking to protect business interests including the lucrative sugar plantations, Thurston set the overthrow in motion. He convinced American diplomat John L. Stevens to send the USS Boston and its 162 American Marines and sailors to the Kingdom under the pretenses of protecting American life and property. Upon arrival, the military was used to uphold the Western coup plotters’ claim to power and subdue Hawaiian resistance.

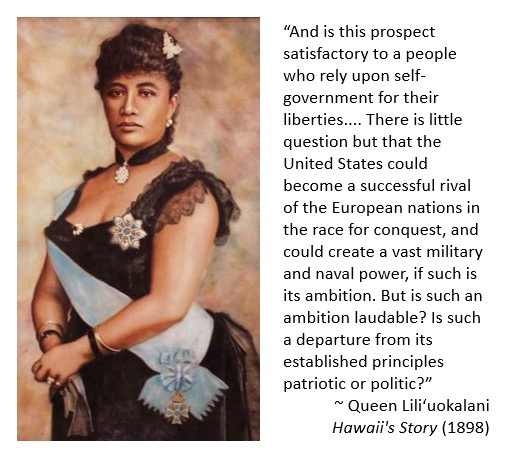

In Hawaii's Story (1898), Queen Liliʻuokalani described her people’s dismay at being betrayed by the United States.

“It had not entered into our hearts to believe that these friends and allies from the United States, even with all their foreign affinities, would ever go so far as to absolutely overthrow our form of government, seize our nation by the throat, and pass it over to an alien power.....

“If we did not by force resist their final outrage, it was because we could not do so without striking at the military force of the United States.”2

Five years after their successful overthrow, the McKinley administration’s naval successes in defeating Spain’s warships gave new impetus for annexing the Hawaiian Islands. Days after defeating Spain’s fleet of ships in Santiago Bay, Cuba, Congress heeded McKinley’s call to adopt the islands.3 McKinley’s argument for annexation had been bolstered by the nation’s new military victories and interests in creating a naval outpost in its growing empire. The Hawaiian Islands, located 2,400 miles away from the U.S. mainland, became part of the United States of America.4

Hawaii’s story not only foreshadowed the U.S betrayal of Cuba but also presages the risks accompanying American overtures such as those Trump is making to Greenland. Hawaiian statehood was not granted until March 11, 1959, years after Japan struck Pearl Harbor, on December 7, 1941.

A worse fate was heaped upon Filipinos. Hours after that the Pearl Harbor strike, Japan bombarded the U.S. territory of the Philippines. In The United States of War, anthropologist David Vine notes that the only parts of the United States to be occupied by a foreign power during World War II were its territories including Guan, the Philippines, Wake Island, and parts islands of Alaska.

“Few know that far more Filipinos died than any other U.S. nationals during the war: 1,111,938 Filipinos, compared to 407,316 U.S. military personnel. Many Filipinos were slaughtered by Japanese forces. Many died during a U.S. campaign to take back the Philippines that shelled and bombed Manila and other parts of the archipelago into rubble. The military’s near-complete disregard for civilian casualties would have been unthinkable if Japanese forces had occupied one of the forty-eight states.”

On July 4, 1946, the Philippines was finally granted independence. The new government promptly entered into an agreement to lease out military bases to the United States.

A Coup and a Canal in Panama

Not only did President Trump insist his administration was reclaiming Alaska’s majestic mountain for President McKinley and going to “get” Greenland, he also insisted that his administration would be “reclaiming the Panama Canal.” The President said that the Canal was “built by Americans for Americans.”

The man-made waterway, which cut through Panama to connect the Caribbean Sea to the Pacific Ocean, came “at tremendous cost of American blood and treasure,” Trump explained, adding that “38,000 workers died building” it. But the President’s portrayal of the Panama Canal as a purely American achievement obscures non-American labor and the sacrifices bore by others to make it possible.

Trump is right that the U.S. economic investment in constructing the Panama Canal was unparalleled at the time. The government paid $375 million for its construction. The United States also paid Panama $10 million for rights to build and use the canal.

Missing from Trump’s statement is an acknowledgment of the well-documented fact that the Panama Canal was made possible by America’s role fomenting a coup against the nation of Colombia. In 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt, an avowed white supremacist and advocate for imperialism,5 instigated and militarily supported Panama’s secession from Colombia. Roosevelt initially used two U.S. gunboats to prevent the Colombian military from intervening when 500 secessionists declared Panamanian independence. The Roosevelt administration further neutralized a Colombian military response by creating a blockade of eight U.S. warships to protect the insurgent government.6

The United States recognized the new Panamanian government three days after they declared independence on November 3, 1903. Less than two weeks later, the new government agreed to give the United States rights to build and control a canal through the newly minted republic. In exchange, the United States paid Panama $10 million and promised to ensure its independence from Colombia. One year earlier, the United States offered Colombia $10 million and an annual rent of $250,000 to control the canal area for 100 years. The deal would have been renewable at the “sole and absolute” discretion of the U.S. government. The Colombian Congress unanimously rejected the deal, so the United States soon set about securing the would-be canal passage by other means.7

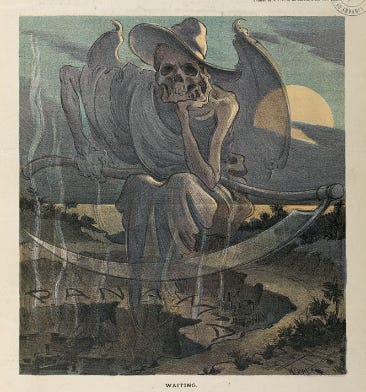

President Trump’s comments about worker fatalities are also misleading. Most scholars estimate that around 28,000 men died building the canal. The main problem with Trump’s characterization of the fatalities is that it lends to the erroneous notion that most of those who died making the canal—“by Americans for Americans,” as he claimed—were, in fact, American. About 22,000 men died during the French-led effort to build the canal in the 1880s. The U.S. phase of the project began in 1904, after the United States helped divide Panama from Colombia, and concluded in 1914. Hospital records at the time show 5,609 men died from either disease or accidents. American cartoonist, Udo Keppler, captured the lethality of constructing the Panama Canal in his 1904 depiction of Death sitting with his scythe at the construction site of the Canal.

Trump would have also been wrong had he said that these 5,609 men were American. Most of those who worked and died building the canal were Antillean/West Indian men of African descent, men from places like Barbados and Jamaica. Of the 45,107 people employed to build the canal during its 10-year U.S. construction phase, 31,071 were Afro-Antilleans.

Trump’s suggestion that all of the men employed to build the canal “by and for Americans” were richly compensated is misleading. Compared to white Americans and European workers from places like Spain and Italy, the West Indies’ workers lived in crowded conditions and were paid the least. Whereas American “skilled laborers” were paid in gold, West Indies workers were paid in silver. They earned between 10 cents and 32 cents per hour, equivalent to around $3.61 and $11.55 per hour. West Indies workers also did some of the most dangerous jobs and suffered life-altering injuries. One Caribbean worker, Constantine Parkinson, began working on the canal at the age of 15. Parkinson lost his right leg, helping to make engineers’ vision a reality.

Learn more about the workers responsible for creating the Panama Canal by watching the 1986 documentary, Diggers. The film is difficult to come by so I am including a 25-minute clip of the film below. You can also view video of the construction of the Panama Canal, between 1913 and 1914, here

Sharpening the Eagle’s Talons for Gaza

Trump uttered the word “Gaza” only once during his Congressional speech despite approving $12 billion in arms sales to Israel as of March 1. Trump’s one and only reference to Gaza was a declaration that his administration was “bringing back our hostages from Gaza.” Since the administration believes just one surviving hostage being held by Hamas is a U.S. citizen, Trump’s choice of words clearly indicates who he identifies with and who he does not.

Who he does not identify with is clear from the fact Trump has said nothing about the pain and suffering being endured by the tens of thousands of Palestinian men, women, and children enduring what leading human rights experts and organizations including Amnesty International have declared a genocide.

Trump has acknowledged the humanity of Palestinians about as much as William McKinley acknowledged Cuban and Filipino humanity during the Spanish-American War. Trump appears unaware of the pain endured by children like 13-year-old Mohammed Al-Agha. Mohammed’s father, mother, and three siblings, ages 11, 10, and 8 were all killed due to Israeli military attacks. Trump is either unaware of or disinterested in American healthcare workers documentation of pre-teen children “shot in the head or chest” by Israeli snipers.

Though he had little to say about Gaza during his March 5 address, President Trump took time to tout his idea of cleansing Gaza of Palestinians and turning their home into the “Riviera of the Middle East” on his Instagram page on February 25. The 33-seconds video imagines Gaza as a decadent resort community peppered with luxury cars, yachts, skyscrapers, and powerful men. Trump dances with a thinly clad woman. A suit-wearing international traveler throws dollars into the air. Jubilant children on a beach jump up to grab the bills. A smiling Elon Musk eats at the resort restaurant. Meanwhile a voice sings, “Trump Gaza shining bright. Golden future, brand new light.”

Driving home that golden future, a child holds a gold balloon shaped as Trump’s head. Trump also appears as a gold statue at his name is emblazoned on a larger tower. The Palestinian people are absent unless presumably woven into the video’s buffoonish caricature of the Middle Eastern other, one that would make even Edward Said, author of Orientalism (1979), cringe. The video comes on the heels of another video Trump released. Titled “ASMR,” the video featured immigrants being chained and expelled from the country. We should view this new Gaza video as another example of autocratic ASMR.

Interestingly, the creators of the video insist that the video was a satirical experiment meant to test out a new technology. They say they did not intend for it to be given to the President or shared by him. But what they may find satirical is what Trump sees as golden. President Trump embodies much of the American consumerist ethos. He transparently expresses his strictly pecuniary values. His interest in Gaza is the same as his interest in Greenland: money and, when relevant, the strategic military positioning to uphold commerce. As CBS News summarizes,

“Its location between the U.S., Russia and Europe makes it strategic for both economic and defense purposes - especially as melting sea ice has opened up new shipping routes through the Artic. It is also the location of the northernmost U.S. military base.”

In this respect, Trump’s interests in Greenland are the same as McKinley’s interests in Hawaii, Cuba, and the Philippines and Roosevelt’s interests in the Republic of Panama. The interest is in exploiting each for the financial gain of the economic elite in the United States. Trump’s promise to Greenland, made during the Joint Address to Congress, that he would keep them “safe” is much the same promise Roosevelt offered the Panamanian secessionists. Similar promises were also given to the Cubans during the Spanish-American War.

Taking Trump Seriously and Rediscovering Our (Anti)Imperialist Roots

Some are convinced that President Trump is not serious about his stated ambitions to “get” Greenland or Canada or Gaza. They believe he is a dynamic amalgamation of jester and skilled negotiator, balancing good humor and tough-talking diplomacy. But Trump’s conscious exaltation of President William McKinley—grounded in McKinley’s role in the Spanish-American War, which jumpstarted U.S. empire building—along with his funding of Israel’s military bombardment of Gaza and his repeated insistence that the United States will obtain Greenland and the Panama Canal, ought to be taken seriously. Panamanian president, Jose Raul Mulino, and Greenland's Prime Minister, Múte Bourup Egede, certainly are.

Following Trump’s speech, the Panamanian president wrote that the “Panama Canal is not in the process of being reclaimed… the canal is Panamanian and will continue to be Panamanian.” Similarly, Greenland’s Prime Minister said that she and her people “don't want to be Americans, nor Danes; We are Kalaallit. The Americans and their leader must understand that. We are not for sale and cannot simply be taken.”

Yet the very notion that something or even someone is not for sale confounds the very essence of President Trump’s worldview. More importantly, American imperialism, as we have seen, does not seriously take the target territory’s interests into consideration. “No” is not an allowable answer. Thus Trump’s confidence that the United States will get Greenland “one way or another.”

Egede’s plea that the Trump respect her people’s autonomy and opposition to U.S. integration brings us back to 19th century Hawaii. As U.S. leaders debated annexation, Queen Liliʻuokalani urged the Americans to carefully consider their nation’s trajectory. “Is the American Republic of States to degenerate, and become a colonizer and a land-grabber?,” she asked.

“And is this prospect satisfactory to a people who rely upon self-government for their liberties....There is little question but that the United States could become a successful rival of the European nations in the race for conquest, and could create a vast military and naval power, if such is its ambition. But is such an ambition laudable? Is such a departure from its established principles patriotic or politic?”

These questions reverberated through Mark Twain’s essay, “To the Person Sitting in Darkness” (1901). Twain sardonically queried the U.S. public, asking,

“shall we go on conferring our Civilization upon the peoples that sit in darkness, or shall we give those poor things a rest? Shall we bang right ahead in our old-time, loud, pious way, and commit the new century to the game; or shall we sober up and sit down and think it over first?”

These ethical-humanistic questions have been hushed by decades of “polite” political discourse and what is termed “soft” power, in which U.S. leaders cloak their use of strategic and economic force in the garb of democracy-promotion and behind the scenes wrangling.

President Trump’s raw bellicosity reveals the unambiguous ugliness of the doctrine that might-makes-right. However unintentionally, Trump tears away at the carefully concocted veneer of American nobility by holding up figures like McKinley and past territorial grabs like that of the Panama Canal.

Trump’s rhetoric necessitates the use words previously deemed too incendiary for respectable civic discourse. Words like “empire” and “imperialism.” How are we not to use the word imperialism8 when Trump openly calls for taking distant lands and extracting beneficial resource deals?

The time has come to reconvene the robust and lively debates around empire and imperial policy that took place at the end of the 19th century and start of the 20th century. Hanging in the balance is not only the fate of others around the globe but also our own. For it may be that President Trump is interested in more than instigating autocratic changes domestically. He may also wish to dig the “eagle’s talons” into other lands. The harms of such a choice will undoubtedly befall us all.

Please share and like this post by clicking the heart icon.

Invite Dr. Nall to Speak

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook or by leaving a comment.

The United States claims an additional nine uninhabited territories.

Following the overthrow, President Grover Cleveland refused to annex Hawaii Islands, arguing that the sugar interests had taken matters too far and unjustly deposed the Kingdom’s Queen. So the white leadership in charge of Hawaii proclaimed it an independent “republic.” In reality Hawaii become an independent state autocratically run by the men who overthrew indigenous leadership with the help of the U.S. military. As Steven Kinzer explained, under the new constitution,

“most legislators would be appointed rather than elected, and only men with savings and property would be eligible for public office. This all but excluded native Hawaiians from the government of their land, and a few months later, a group of them staged an abortive uprising. The former queen was among those arrested….[She] was sentenced to five years in prison and freed after two.”

Congress had rejected McKinley’s 1897 call to annex Hawaii.

For contrast, the Florida Keys are 1,972 miles from Van Buren, Maine.

This characterization is based on well-documented primary source text in which Roosevelt expressly states these positions. Read his words for yourself.

See chapter three of Kinzer, Stephen G. Overthrow: America's Century of Regime Change from Hawaii to Iraq. Times Book, 2006.

See Paterson, Thomas G., et al. American Foreign Relations: A History Since 1895. 5th ed., vol. II., 2000. pp. 33-37.

David Vine defines imperialism as “the practice by one country, state, or people of forcibly imposing and maintaining hierarchical relations of former or informal rule, domination, or control over a significant part of the life of other groups of people such that the stronger shapes, or has the ability to shape, significant aspects of the political, economic, social, or cultural life of the weaker.”

Very impressive essay...There's no way to put lipstick on the Imperialist pig...As General Smedley Butler said, I never fought in a war that wasn't for American business...But all empires overreach, and fail...

https://substack.com/@johnshane1/note/c-99654016