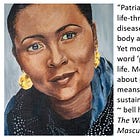

Video #3: bell hooks’ Intellectual Labors of Love

On February 12, 2023, I discussed bell hooks’ life and work before the Unitarian Universalist Fellowship of St. Augustine, Florida. I built on ideas previously discussed in a set of writings published in Humanities in Revolt beginning in December 2022 and on into 2023.

There was a great outpouring of love and appreciation for bell hooks when we learned she had died of kidney failure on December 15, 2021. hooks helped many better understand the character of sexism and racism and how these forms of human oppression uniquely intersect with other dimensions of social life. She also taught many of us how to think more critically, communicate more courageously, and love more authentically.

As I discuss in the talk, I've had a special connection to hooks’ work since I first discovered late in my formal education—in graduate school. She taught me that the feminism best known to the public was “reformist feminism,” and that it was just one of several flavors. And though all feminisms sought to combat sexism, only a feminism that placed patriarchy at the center of its analysis could accomplish that goal.

Feminism at its best, according to hooks, was “revolutionary” and “visionary.” And visionary feminists were not satisfied with merely “improving” a society rife homophobia, racism, sexism, and classism; they wanted to radically reimagine it. In Feminism is for Everybody (2000), she wrote,

“Revolutionary thinkers did not want simply to alter the existing system so that women would have more rights. We wanted to transform that system, to bring an end to patriarchy and sexism.”

I always appreciated the style as well content of hooks’ writing; its directness, daring, and clarity. Here was a thinker who didn't hide behind verbosity or obscure academic lingo. Of course she knew her way around a thesaurus, but she wasn't writing for academic committees. And she was more interested in communicating with everyday people than impressing them.

That style of writing spoke to me, as someone who felt like something of an outsider inside academia; someone who resisted adopting the obfuscating “in-group” speak, and wanted to keep a foot firmly planted on the firm ground of ordinary life experience and understanding. Her style of writing reflected her ethical commitments to honor human dignity and combat injustice; it was not just a means but also an end.

I was surprised and saddened to learn of her passing. I didn’t know anything about her health condition so I wasn’t expecting her to die before turning 70. (Less than two months later renowned Buddhist and peace intellectual, Thích Nhất Hạnh, would also pass, leaving the world with yet another palpable loss.) I also found it ironic that hooks’ death was treated as a major news event, with coverage in news publications across the country. bell hooks probably received more mainstream media coverage in death than she did alive. And this worried me.

I worried that the dominant culture she went to such pains to critically examine—and wanted to radically transform—would foster a narrative about her life and work that fit its own interests and would dull and simplify her most incisive critiques. I was particularly concerned that hooks’ bold and intentionally radical critique of not only racisms and sexism but also militarism and economic exploitation—class—would be papered over as has been done with Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr’s social analysis.

hooks’ spent a lot of her later years focused on class as a central though too easily overlooked dimension of human oppression. This aspect of her work is not highlighted as often as her critique of racism and sexism are. The likely explanation for this imbalance speaks to the very insidious function of classism: namely that many with the privilege to professionally explore social systems are comparably protected from the worst abuses and insecurities of poverty. As she wrote in Class Matters (2000), a book rarely mentioned in the many eulogies published in the wake of her death:

“The evils of racism and, much later, sexism, were easier to identify and challenge than the evils of classism. We live in a society where the poor have no public voice. No wonder it has taken so long for many citizens to recognize class—to become class conscious.”

Throughout her career, hooks made a point of highlighting the necessity of amplifying the voices of those most directly effected by oppression. This required, for example, amplifying the voices of people of color when addressing racism and women of color when trying to make sense of the particular plight of women of color dealing with racism and sexism. The unique problem of class is that those most adversely affected by economic exploitation are the furthest from the proverbial public microphone.

Following her death I was also concerned that hooks’ emphasis on men’s experience as people with gendered identities was not sufficiently recognized. I wanted to highlight her illuminating analysis of the damage patriarchal culture does to men and boys as well as women and girls. In one The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love (2004), hooks empathized with men living lives shaped by patriarchal culture. She highlighted their pain, drawing on her own experiential knowledge with the men she loved.

She also insisted that men take greater responsibility to challenge patriarchal indoctrination and practice, both for their own good and that of the women who suffered various forms of “psychological terrorism” and outright physical violation at the hands of patriarchal men.

hooks’ work took on new importance in January 2023. That’s when the Florida Department of Education, under the leadership of Governor Ron DeSantis, identified her by name in its list of objectional materials and authors found in the Advanced Placement (AP) African American Studies course. The AP course debuted the prior year and was the result of social clamor to reckon with our nation’s racist history following the 2020 killing of George Floyd by Minnesota police officer, Derek Chauvin.

The Department of Education took particular issue with hooks’ phrase, “white supremacist capitalist patriarchy,” and threatened to ban the course unless authors including hooks and concepts like “intersectionality” were not removed from the curriculum. These targeted ideas constitute what Governor Ron DeSantis’ general counsel, Ryan Newman, defined, before a federal judge in December 2022, as “woke,” “the belief there are systemic injustices in American society and the need to address them.” hooks most certainly was “woke,” by this definition, and so were countless agents of change in U.S. history including Dr. Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Coretta Scott King.

On February 1, 2023 the College Board’s revised curriculum for the AP African American Studies course excluded hooks and all other secondary source readings. The college educators who made the College Board decision vehemently denied that political considerations influenced their decision.

Despite changes to the course, Governor DeSantis and the Florida Department of Education refused to adopt the AP African American Studies course for Florida schools. Internal documents within the state’s Department of Education reveal that officials criticized the course for offering a “one-sided” view of slavery and failing to present “opposing viewpoints.” That some in authority believe we need to spend more seeing the “other side” of slavery at the very moment we begin to grapple with the conscience shocking realities of our nation’s past is all the evidence we need to know hooks’ ideas are as important as ever.

Excerpt from “bell hooks’ Intellectual Labors of Love”

On December 15, 2021, the world lost one of the great public intellectuals of our day, Gloria Jean Watkins, better known by her pen name, bell hooks. hooks was birthed by Rosa Bell Watkins on September 25, 1952, and grew up in a working-class African-American family as one of six children. Her father worked as a janitor and her mother worked as a maid for white families. As a child, hooks experienced segregated public schooling first-hand.

hooks passion for books and ideas led her to earn a BA in English from Stanford University in 1973, an MA in English from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1976, and then a doctorate in English from the University of California, Santa Cruz in 1983. Before completing her undergraduate studies, hooks, aged 19, began writing what would later become an influential contribution to feminist thought: Ain't I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism. The book was later published in 1981; one of a catalogue of more than 30 books, written over 40-years, exploring love, feminism and black men and women, men and masculinity, and critical thinking and teaching. She also wrote poetry, personal memoirs, and children’s books.

Since her passing, many have focused on bell hooks’ invaluable contribution to understanding the intersection of racism and sexism. These aspects of her work do, indeed, merit focused attention. Yet so do some of her less discussed examinations of class exploitation, the price men pay for their male privilege in a patriarchal society, the centrality of the ethic of love in movements for justice, and what it means to think critically and uphold the fundamental principles of a democratic society including freedom of expression….

Unlike reformist thinkers, bell hooks and other black feminists like the Combahee River Collective didn’t want women and people of color to be “integrated” into the existing society. They wanted to dig to the roots of our social sickness—patriarchy, racism, militarism, and economic exploitation. This is why hooks, like Rev. King, would have challenged the uncritical praise of the first “all-woman team of aviators” to conduct a flyover during [the 2023] Super Bowl.

Reformist feminism would have us believe that justice is achieved when women—and other marginalized groups of people—have equal access to participate in the dominate institutions of our society such as the military. Radical feminists like hooks joined Rev. Dr. King in seeing U.S. militarism as one of the sources of injustice both at home and abroad. hooks would have asked us to consider how the Navy and NFL’s widely publicized entertainment spectacle used reformist feminism to promote their brands and turn our attention away from pressing questions such as military spending.

bell hooks’ feminism was egalitarian and sought to address pain and suffering wherever she observed it. She refused reductive analysis of oppression and boldly challenged us all to see how ideologies and practices of dominance worked together to produce an interlocking injustice.

In the video, Cultural Criticism and Transformation (1997), she said, “I began to use the phrase in my work 'imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy' because I wanted to have some language that would actually remind us continually of the interlocking systems of domination that define our reality and not to just have one thing be like, you know, gender is the important issue, race is the important issue, but for me the use of that particular jargonistic phrase was a way, a sort of short cut way of saying all of these things actually are functioning simultaneously at all times in our lives….”

To foster a truly caring-just society we would need to go to the roots of deep-seated problems. This would require radical thought and action, not mere reform.

Paid subscribers can view the previous videos below.

Please share and like this post by clicking the heart icon.

Invite Dr. Nall to Speak

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook or by leaving a comment.