What's Wrong with Moderation?

What Our Feminist and Abolitionist Foremothers and Forefathers Teach Us about Social Transformation and the False Compromise Fallacy

Commentators in the mainstream media would have us believe social progress is the result of temperate, pragmatic political decision making. Our best chances of making a better world, they advise us, is to put practical compromise before the “extremes” of principled conviction. Change only comes when we are willing to choose the middle road between any two set of polarizing camps, or so we are told.

The women's rights and abolitionist movements sing a very different song, however, one that sees moderation’s relationship to social change the way Florence Welch sees moderation’s relationship to love. In her song, “Moderation,” Welch, frontwoman for Florence and the Machine, spurns her lover’s pleas to love with restraint.

“Want me to love you in moderation

Do I look moderate to you?

…You got me looking for validation

Pastures new

Want me to love you in moderation

Well, who do you think you're talking to?”

Abolitionism and the women's rights movement that grew out of it reminds us that the unprincipled embrace of moderation is often an obstacle to movements for justice and social transformation. Our feminist foremothers and forefathers teach us that social transformation often requires discordant dissent and that the claim that moderation is always best is fallacious.

The most laudable of social changes in the United States—curtailing exploitative child labor, abolishing slavery, ending legally-mandated segregation, enhancing child welfare protection, combating homophobia, achieving marriage equality, and the struggle for women’s enfranchisement—were born of immoderate advocacy, political radicalism, and personal sacrifice.

One of the great ironies of the first wave of women’s rights activism in the United States is that it was partly spurred by women’s sexist treatment within the movement to end slavery. Lucretia Mott was inspired to join Elizabeth Cady Stanton to organize the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848, in part, because she was prevented from participating in the 1840 Anti-Slavery Convention in London. Stanton and Mott’s decision to hold such a convention was not a moderate act.

Holding the Seneca Falls Convention was itself a radical and impertinent transgression of polite society’s social norms. We can better understand its daring by considering how the Grimké sisters—Sarah and Angelina—were condemned after speaking out against slavery, in 1836, as members of the Quaker organization called the Society of Friends. At the time, the Council of Congregational Ministers of Massachusetts issued a statement:

“The power of a woman is her dependency flowing from the consciousness of that weakness which God has given her of her protection…when she assumes the place and tone of man as a public reformer, she yields the power which God has given her for her protection and her character becomes unnatural.”

The presence of women participating in public discourse incensed many. As Angelina addressed a racially integrated abolitionist group at Pennsylvania Hall in Philadelphia on May 17, 1838, thousands gathered in protest. The mob threw stones and broke windows during Angelina’s speech. Rather than fleeing the threat, she integrated commentary on the mob’s actions in her speech and continued her speech. Later in the night the mob “burned the hall to the ground.” Just speaking in public, as a woman, during the early 1800s was revolutionary.

At the Seneca Falls Convention, just one-third of the attendees actually signed the Declaration of Sentiments and Resolutions. Many supporters of expanding women’s rights found the document’s demand for suffrage too extreme. One of the staunchest defenders of the resolution was the eloquent orator and former slave, Frederick Douglass who rose to offer a defense of women’s political rights including the right to vote. Douglass later wrote about the event and cause of women’s rights in “The Rights of Women” (1848), published in his anti-slavery newspaper, North Star.

Douglass relayed that, in 1840, some had left the abolitionist movement for fear that it would lead to women’s political freedoms. The mere mention of women’s rights evoked “contemptuous ridicule and scornful disfavor” in many.

“A discussion of the rights of animals would be regarded with far more complacency by many of what are called the wise and the good of our land, than would a discussion of the rights of women.”

Those truly committed to the cause of human freedom, Douglass explained, were called to stand with the daring, nascent movement.

“All that distinguishes man as an intelligent and accountable being, is equally true of woman, and if that government only is just which governs by the free consent of the governed, there can be no reason in the world for denying to woman the exercise of the elective franchise, or a hand in making and administering the laws of the land. Our doctrine is that ‘right is of no sex.’”

Such a position was beyond the pale for many, including some in the abolitionist movement. Yet it was a position that women and men of principle and conviction took even as it was deemed absurd and impractical by the common sense of their day.

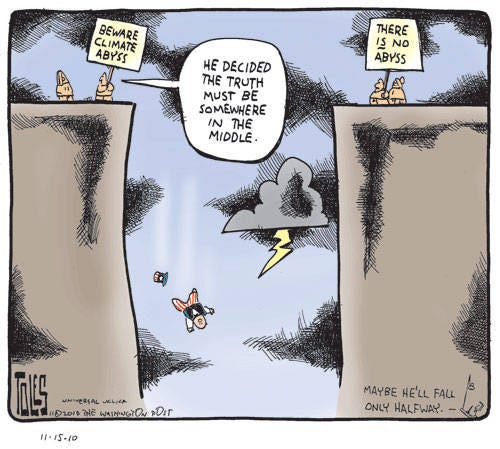

The False Compromise Fallacy

Our feminist foremothers and forefathers’ example helps us grasp the Argument to Moderation, also known as the False Compromise or Middle Ground fallacy. We commit this fallacy when we mistakenly believe that something is necessarily true or good just because it is “moderate” or in the “middle” of two conflicting views.

Consider what the moderate position would have been between the Grimke sisters’ claim to the right to publicly advocate for their beliefs and the Council of Congregational Ministers of Massachusetts contention that it is unnatural for women to do so. Should our foremothers have found a half-way point between women’s equal share to political freedom and being restricted to the home living in subjection to men? We all know that the answer doesn’t stand between these two positions. One is right and the other is wrong. The fact that the wrong position was, at the time, also long-standing and culturally commonplace did not mean that it was right.

Exactly 100-years before the Seneca Falls Convention, the French political philosopher and innovator of the separation of powers, Montesquieu, published The Spirit of Laws. In the book, he warned that a free and democratic society was jeopardized by “extreme equality” among those who are not of equal competence and ability. Extreme equality would likely reduce not only respect for government leaders, old age, and parents, he wrote, but also “deference to husbands will be likewise thrown off, and submission to masters.” What consequences would such “extreme” ideas produce? Montesquieu wrote,

“Wives, children, slaves will shake off all subjection. No longer will there be any such thing as manners, order, or virtue.”

We quickly realize the error of presuming the goodness of the moderate position when we understand that the subjugation of women was once deemed the “decent,” “moderate” position and full equality viewed as the radical extreme on par with no liberty.

Complacency and Cowardice Masked as Compromise

Despite the pretense usually given, appeals to moderation are usually motivated by cowardice and complacency more than reason and intellect. Acknowledging this is difficult because it requires us to look honestly within ourselves and realize that, however morally and politically enlightened we imagine ourselves to be, most of us these insights are the fruits of others’ labor.

We stand against racism, sexism, homophobia, autocracy and the like, not because we are inherently more ethically enlightened—just plain better—than those who came before us. Mostly, we are lucky. Lucky to be benefactors of those who came before us and not only forged a political-social path of expanded liberties but also forged paths of moral clarity. Most of us stand for principles and causes that have, for some time, been woven into the fabric of dominant culture. And while we ought to continue standing for these principles, we should also recognize that doing so is no great ethical achievement of individual conscience or character.

Standing for the morally right position against power, popular opinion and long-standing custom is an entirely different experience. The difference between adopting established moral norms and revolting against deeply entrenched cultural values is poignantly captured in Angelina Grimke’s bold letter, written in 1835 after a pro-slavery riot in Boston. Grimke urged abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison to continue with the cause despite the danger of doing so.

“If persecution is the means which God has ordained for the accomplishment of this great end, Emancipation; then…I feel as if I could say, let it come; for it is my deep, solemn, deliberate conviction, that this is a cause worth dying for.”

Angelina went on to say she would prefer the achievement of abolition through the martyrdom of righteous abolitionists than the horrors of a war, spilling the blood of the supporters of slavery. She stated that she believed abolition would prevail, but its advocates must be

“willing to suffer the loss of all things—willing to be the scorn and reproach of professor and profane. You must obey our great Master's injunction: ‘Fear not them that kill the body, and after that, have nothing more that they can do.’ You must, like Apostles, ‘count not your lives dear unto yourselves, so that you may finish your course with joy.’”

To achieve the goal of ending slavery might well mean suffering persecution and even death. The “immoderacy” of their cause, Angelina makes clear, was an irrelevant consideration. The question, simply, was whether or not the cause in question followed from one’s deepest moral convictions.

The Virtues of Courage and Disobedience

Our feminist foremothers teach us that discomfort is no barometer of right action and principle, and that systemic oppression isn’t defeated without defiance and fortitude. We must be prepared to reverently defy conventional thought and sensibility in the service of a love of life, humanity, and freedom. Fortitude is required to endure the inevitable tumult that accompanies significant social transformation.

In June 1873 Susan B. Anthony stood trial for the crime of election fraud for having joined a group of women in voting in Rochester, New York. Near the end of the proceeding the judge announced her guilty verdict and fine of $100. Asked if she had any final words, Anthony replied,

“I will never pay a dollar of your unjust penalty. All the stock in trade I possess is a debt of $10,000, incurred by publishing my paper—The Revolution—the sole object of which was to educate all women to do precisely as I have done, rebel against your man-made, unjust, unconstitutional forms of law, which tax, fine, imprison and hang women, while denying them the right of representation in the government; and I will work on with might and main to pay every dollar of that honest debt, but not a penny shall go to this unjust claim. And I shall earnestly and persistently continue to urge all women to the practical recognition of the old Revolutionary maxim, ‘Resistance to tyranny is obedience to God.’”

In reading the correspondences and speeches of advocates of abolition and women’s rights, one is struck again and again by the prioritization of ethical imperatives over political calculations. Reading between the lines we also find a rich faith in human agency to generate the changes demanded by our moral conviction and imagination. This is a striking deviation from the fatalistic skepticism in the prospects of change espoused by contemporary political analysts.

Transformative movements against slavery and sexism teach us that social and cultural systems of oppression are not alone defeated through modest reform or “natural” progression. On August 4, 1857 Frederick Douglass delivered a speech on the emancipation of slaves in Great Britain's colonies in the West Indies, which took effect in August 1834. During his speech, Douglass articulated what he termed “the philosophy of reform.” Social reform—progress, he explained, is as dependent on strife and struggle as the cultivation of crops is on plowing the earth.

“Those who profess to favor freedom and yet deprecate agitation are men who want crops without plowing up the ground; they want rain without thunder and lightning. They want the ocean without the awful roar of its many waters.”

Societal change entails the alteration of power relations. Egalitarian social change, more specifically, involves wresting power—authority, privilege, command of resources, culture, and law—from those most invested in maintaining the existing state of affairs. Such change will not and has not emerged, organically, without willful, rebellious insistence. Douglass wrote,

“The struggle may be a moral one, or it may be a physical one, and it may be both moral and physical, but it must be a struggle. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.”

Those who would have us believe that moderation is the path to social justice and transformation guide us to absurdity. Injustice, Douglass instructs us, grows in proportion to our tolerance for it.

“Find out just what any people will quietly submit to and you have found out the exact measure of injustice and wrong which will be imposed upon them, and these will continue till they are resisted with either words or blows, or with both. The limits of tyrants are prescribed by the endurance of those whom they oppress.”

In simple and direct terms, tyrannical forces will subject the oppressed to whatever they are willing to endure. The limit of this abuse is set by the visceral intolerance of the oppressed to endure further dehumanization.

The expectation that injustice—that the unfair allocation of power and ethical regard in society—can be overturned through compromise, alone, and without upset and discomfort defies reason and experience. Resounding Angelina Grimke’s words written down some twenty-years earlier, Douglass reminded his audience that the oppressed and the wronged are tragically responsible for their liberation. “If we ever get free from the oppressions and wrongs heaped upon us, we must pay for their removal.” The cost of such liberation is high, requiring a “labor” of “suffering” and “sacrifice.” We ought to reflect upon these words.

Have we really grasped what was required to foster the societal transformation so many of us, today, enjoy? Do we understand the vision, commitment, and principled conviction—the faith in human freedom of will—required to defy the intransigent trajectory of history; to turn its locomotive stride against itself, against all odds? Do those given authority to guide our thinking about society and politics possess the knowledge, insight, and integrity—the imagination—to foster let alone maintain the kinds of transformation manifested by the change agents who birthed abolitionism and enfranchisement?

Those who would have us believe that social change results from moderation—from taking the middle path between two radically opposed views—would have had us live in a world where slavery and sexism and grueling child labor were merely “moderated” rather than eliminated. Moderation did not bring an end to slavery, neither did it guarantee women’s most basic political rights. The willingness to endure indignities, to be trifled into splitting the difference between denigration and full humanity furthers us from the goal of honoring the moral equality of all. As Susan B. Anthony instructed us, the “cautious” often stand in the way of social change. In 1860 she wrote:

“Cautious, careful people, always casting about to preserve their reputation and social standing, never can bring about a reform. Those who are really in earnest must be willing to be anything or nothing in the world’s estimation, and publicly and privately, in season and out, avow their sympathy with despised and persecuted ideas and their advocates, and bear the consequences.”

The best of our present cultural values and traditions were gifted to us by incendiary spirits who followed Eve’s noble footsteps of defiance.1 That act of disobedience in the Garden gifted humanity more than knowledge but also, simultaneously, human agency—freedom. Our feminist foremothers challenge us to follow Eve in courageous pursuit of something greater, something more human than blind obedience to tradition and authority: reverence for life in all of its poetic even if disassembling dynamism.

Self-Examination and the Emulation of Excellence

The best of our feminist foremothers’ example directs us to embrace intellectual independence and ask questions of the ordinary rather than be lulled by the comforts of conformity. Rooting out injustice begins with the difficult though overlooked challenge of recognizing injustice as such.

One of the greatest achievements of oppressive power is to ensure those who are subject to oppression internalize the beliefs, assumptions, and expectations of those with privilege, culturally and institutionally favored as superior. Our ability to so quickly recognize the immorality of denying women their full humanity as men’s moral equals; our recognition that women’s value is obviously not determined through their usefulness to men; our now visceral disgust at the thought of women being subjected to men’s discipline must be recognized as something more than a “natural response to injustice.” It is an enlightened good sense born of rebellious, recalcitrant women—and some men—who dared to look upon a patriarchal world with a lens not of that world.

Susan B. Anthony, Sojourner Truth, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper and countless other transformative change agents deserve more from us than idle admiration. Putting their effigies on currency and postage stamps does not take the place of honestly reflecting the radical character of their ethical and political projects. We are obligated, by decency, I think, to contemplate how easily discomforted many of us are by those challenging the status-quo of our age. When the fruits of revolutionary labor have been planted into cultural common sense, society tends to pay tribute to that labor with boastful and self-congratulatory pride. The hard truth is that many of us who, today, claim the fruits of this revolutionary labor wouldn’t have had the insight or courage to stand up to cultural convention and power, at the time.

To authentically honor the change-agents’ labors that, today, nurture not only justice but our own moral decency, we should recognize the commonality of human cowardice and how it operates as one of the greatest resources for upholding human oppression. This cowardice nourishes the reflexive belief that now is not the time for change and that we are not the ones who can be expected to shoulder the weighty responsibility of enacting it. Too often commemorative ceremonies honoring the achievements of change agents function as ritualistic subterfuges, signaling our virtue while excusing our moral indolence—our inaction in taking up the mantel of advancing social progress.

Our task, today, is to see through the dehumanizing fog of our present; to ask what cruelty, what dehumanizing presumptions and practices go unnamed and unseen before our very eyes? What dehumanizing ideologies and practices might we be perpetuating through our unthinking biases and choices? In what ways must we be willing to undergo personal transformation in order to enable others to experience their fullest humanity?

As we contemplate such questions let us not allow purely practical calculations of likely outcomes to have outsized sway in our thinking. We can do no better, I think, than to recall Frances Ellen Watkins Harper’s remarks, on April 14, 1875 before the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery:

“...let no misfortunes crush you; no hostility of enemies or failure of friends discourage you. Apparent failure may hold in its rough shell the germs of a success that will blossom in time, and bear fruit throughout eternity.”

If you enjoyed this post please share it with others and like it by clicking the heart icon. Be sure to subscribe if you haven’t already.

Invite Dr. Nall to Speak

Dr. Nall delivers energetic live presentations and engaging workshops on the subjects featured in Humanities in Revolt. Those interested in booking a workshop or talk can get in touch through Facebook or by leaving a comment.

In works including Escape from Freedom (1941), Erich Fromm contends that the Adam and Eve story whereby they eat of the tree of knowledge, despite God’s command not to do so, mythically conveys the birth of human consciousness and freedom through a primordial act of disobedience. Fromm likens the Adam and Eve story to the myth of Prometheus who defies Zeus to aid human beings in obtaining fire.

Wonderful, powerful essay!

Fredrick Douglas, the magical negro, why must everyone be like him in order for society to function properly? Being an ordinary wanker is too troublesome? Maybe making a billion more will solve that problem, maybe.

Drilling for clarity & compassion on a superfund site.